“Inspirations and Influences” is a series of articles in which we invite authors to write guest posts talking about their Inspirations and Influences. In this feature, we invite writers to talk about their new books, older titles, and their writing overall.

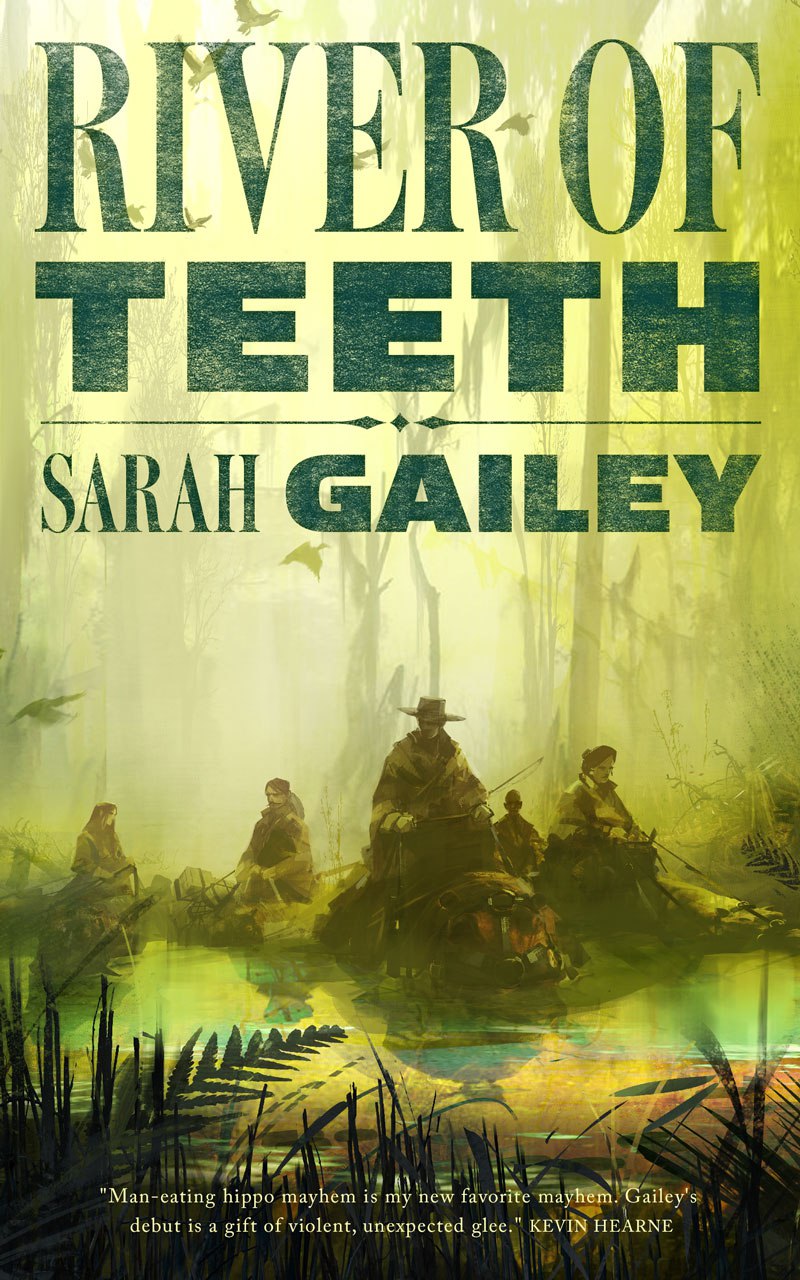

I recently read – and ADORED – Sarah Gailey’s River of Teeth and so it was only natural to reach out to the author and invite her for our inspirations and influences feature. She said yes, and the lovely result is below.

![]()

My first memory is of sitting in a library. Nubby carpet, stale air, paper-smell, everything grey or tan and covered in plastic.

I was a very small wandersome kind of child — a lost-on-purpose child, always looking under leaves and behind shelves. I spent a lot of time at the Alameda County Library, and the day of this memory was no exception. I was wearing a dress that was red with white dots on it.

There was a story hour afoot, and I had snuck away. I had heard and read the story before. The lady reading did the voices wrong. I was bored. There were discoveries to be made. I trod softly into the low, brightly colored shelves of the children’s section (which I was already starting to disdain as the baby section) and stopped short.

There was magic.

Magic, real magic. Right there in front of me. All the adults and older kids I’d been stupid enough to believe told me that magic wasn’t “real” — but it was right. There.

A moment of unadulterated triumph.

It was a golden beam of floating motes. They didn’t all float up, and they didn’t all float down. They drifted in a strange kind of synchrony that I couldn’t understand. I didn’t know what they were or why they were there or why they were moving the way they did, but I knew they looked exactly like something my heart called to. They looked like magic. They were real.

I lifted my fat, clumsy little hand (I hated it then, and for the duration of my childhood: having hands that couldn’t do the clever things that I wanted them to do) and I tried to wave it through the motes to see if I could direct them.

And then some lady — some lady who I didn’t even know — appeared at the end of the aisle and lifted her hand and did a strange, infantile wave at me. Her wrist was floppy, and she wagged her hand at me all of a piece, like none of her fingers knew what her arm was up to.

I tried to wave her off: go away, you, I’m much too busy for the silly games that grown-ups like to play.

She did another odd wave.

I gave her a real wave, a firm one, a yes hello I see you wave, and she was delighted. She laughed and waved again, and then she turned to her friend and pointed at me. I was furious once I realized what was going on: she couldn’t see the dust motes from her angle. She thought that I was just some… some child who wanted to wave at people for the puerile joy of watching them wave back. I don’t remember precisely how I reacted, but I remember a sense of shame and fury and an immediate understanding that I could never explain to her what it was that she’d done.

When I learned the word “condescending,” that woman’s face was the first thing that came to mind.

It bothered me for years. It still does — that lady waving at me like I didn’t know how to wave, like I would just wave at a stranger, like I was a child. But that reasoning for my anger (my outrage, my fury) wasn’t quite right. The flavor was off. I was a kid, and I knew I was a kid, and I was used to condescension. I thought about it frequently, and recently, I realized what the truly unacceptable thing about it was.

She interrupted the magic.

I had discovered something important, and I was right on the brink of grasping it. But that woman interrupted the magic. The next time I went to the library, I tried to find the magic — but someone saw me, and they explained what I was looking at.

A sunbeam. Dust. Tiny bits of skin and hair and paper, proof of the library’s poor ventilation system, floating through a sunbeam that would bleach the outlines of books onto the shelves.

The magic was gone. The breakthrough moment of yes it’s real it’s all real was gone.

Every piece of fiction that I write is an exploration of that moment. When I write magic into my stories and into my books, the magic looks like that sunbeam, or at least like what I wanted that sunbeam to become. When I write grit into my worlds, the grit recalls a library volunteer explaining dust mites to a child: commonplace, sensible, and in some understated way, terrible. My villains are the people who never had an opportunity to believe that they were discovering magic. My villains are strange women who interrupt magic in order to wave.

And my heroes — my heroes are the people who ignore the waving woman and keep looking. My heroes are the people who decide that if the magic isn’t here, it must be over there, and they’ll just have to keep trying to get it by any means necessary. My heroes are the people who find the magic and then decide what to do with it (even if that means using it to inflict terrible vengeance on those who would interrupt their discovery).

This seems reductive, doesn’t it? After all, I don’t always write about magic. Sometimes I write about space, and sometimes I write about hippos that eat people. But no matter what world I’m writing, there’s always a wayward little girl somewhere, trying to move her hand slowly through a sunbeam so that she might touch some of the power that she just knows is there, waiting for her. And no matter what world I’m writing, there’s someone there waiting to break into her moment of discovery and claim her movements for their own entertainment.

Whether or not she lets them — that’s what makes the difference between the worlds. That’s what changes whether the girl grows up to be a hero or a villain. That’s what changes the story.

A moment of triumph. A moment of condescension.

A small hand in a sunbeam, finally figuring out why the motes move the way they do, and forming a fist to grasp the power that was right there the whole time.

Hugo and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey lives and works in beautiful Oakland, California. Her nonfiction has been published by Mashable and the Boston Globe, and her fiction has been published internationally. She is a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to her work at www.sarahgailey.com. She tweets @gaileyfrey.

5 Comments

Pretty Terrible | Links Roundup 06/23/17

June 23, 2017 at 10:01 am[…] Sarah Gailey on her inspirations and influences. […]