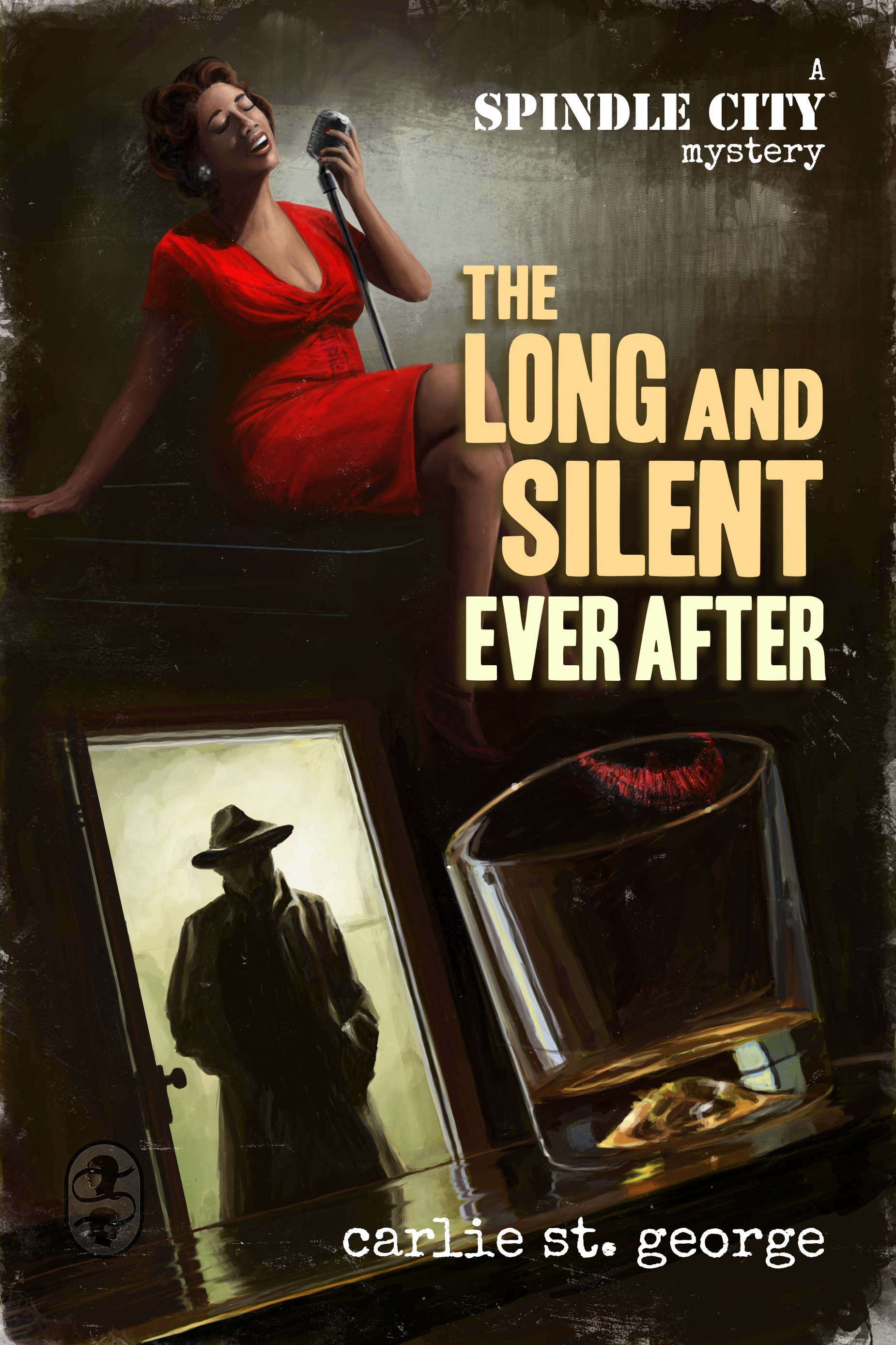

The Long And Silent Ever After by Carlie St. George (Spindle City Mystery #3)

Published 12/15/2015 | 13,34 Words

“Hello, Prince,” the Godmother said. “I’m calling in that favor.”

When Rose Briar–cabaret singer, drug lord, and notorious secret-keeper–disappears without a trace from her club, The Poisoned Apple, Jimmy Prince and Jack are on the case once again. This time, the duo may have bitten off more than they can chew, as their investigation drags them into the path of the Spindle’s greatest and most formidable criminal–one who got her nickname for her tendency to burn her enemies alive.

It doesn’t help that Jimmy is having a hard time focusing on the case, torn between his head’s desire to do the right thing, and his heart’s insistence for that one person who always has three gats, a pen, and a smile at the ready.

But in Spindle City, the long and silent ever after waits for no one–and it’s Jimmy’s turn to dance with dragon.

![]()

Nothing good came of being conscious this early in the morning, but eating jelly donuts in the stiff house was a special sort of low. The sweet-voiced canary on the radio wasn’t helping any, either, considering the last time Santa came to town, I’d caught the Pins for Christmas. At this point, I could guess where I stood with that jolly old bastard.

Doc clearly wasn’t concerned with being nice herself, because she snatched a second donut off the morgue table and said, “Prince, stop being an asshole.”

I shrugged. “Not sure that’s possible. How about my results?”

“How about my dough?”

I slid over a tiny stack of green. A year ago, I’d been flush with cash, but medicine, well, that cost a pretty penny. My piggy bank was drying up fast, and in the last few weeks, I’d started skipping doses just to keep Jack and me fed.

Doc pocketed the cash. “You start taking your pills regular? You’ll live a good, long life. But I’m already seeing signs of permanent damage to your spinal column.”

“And that means…”

“Couple years before you lose all feeling in your gams for good.”

Oh.

I leaned a little heavily into the table. Unperturbed, Doc took another bite of her donut. “The good news,” she said, “is that your paralysis shouldn’t advance past paraplegia, assuming you can stop being an asshole. Which is assuming a lot.”

I scowled at her and pushed my breakfast away. “Thanks, Moreno,” I said, turning to leave. “You’ve been a peach.”

“Prince.”

I turned back. Doc set down her donut, readjusted her specs. “If you’re looking to kill yourself slow, congratulations, you’re doing a bang-up job. If not, a guy like you has options. Use them, will ya?”

“Would you miss me, Doc?”

Doc snorted and turned to one of the stiffs, patiently waiting for his Y. “Miss your green, anyway.”

It wasn’t exactly a rousing endorsement of sentiment, but then again, Doc had idly threatened me with a bone saw this time last year. Who said I didn’t know how to make friends?

On my way back to the office, I passed a group of religious protestors and crossed the street before they could assault me with their anti-vaccination pamphlets. Last time someone tried, I’d clocked him in the face. My knuckles didn’t need the abuse.

Even before the vaccine went into distribution, I figured there’d be problems. Exorbitant costs. Insufficient supply. Spindle City had a long, bloody history of crushing the poor beneath her heel, and I’d worried only the rich would benefit. Turns out, I’d had cause for concern—not only were the rich trying to hoard the vaccine, but there were people, flush and broke alike, who didn’t even want it.

There were Christmas carolers on the other side of the street. I was starting to wish I hadn’t rolled out of bed today.

Jack was sitting on her desk when I arrived at the office, playing a bad hand of solitaire. “You don’t got the cards,” I told her.

“Yeah,” Jack said, and kept playing.

Jack was my receptionist and roommate. She was also already a better gumshoe than any unschooled sixteen-year-old had the right to be, and I didn’t know what the hell I’d do without her. Of course, she was wearing a Santa hat on her head and humming Jingle Bells, so she did have character flaws.

“You have to do that?”

Jack smiled and hummed louder. “No calls,” she said between verses. “Just in case you were waiting for a certain someone to forgive you for being an unbelievably silly ass. That hasn’t happened yet. You should probably call him instead.”

I sighed and lit a gasper as I sank into a chair. “Are we having this argument again?”

“Depends. You realize you’re an idiot yet?”

I exhaled. “I’m not waiting for him to call. That was the whole point of the note. Besides, you seem to be forgetting—”

“Ada?” Jack snorted. “You two are a sham, and you know it.”

“You’re just saying that because you want to skip the rehearsal dinner tonight.” I sure did, anyway. My parents were going to be there. “Besides, I thought you liked her.”

“I do like her. You love Hank.”

Yeah. Unfortunately, that was still true. But my love life had always been, well, complicated. Rose had been sweaty sheets and dark secrets, great for a good time but too slippery for trust. Ella Shah, I fell for her, all right, even if she had been hired to fit Mother for a Chicago overcoat. But she’d been forced to flee the Spindle before that spark had a chance to become something more.

And then, Hank—Hank, who I’d known and flirted with for ten years, who worked side by side with my mother, assisting in all her clerical and terrorism needs. Hank was the only man I knew who always had three gats and a pen at the ready.

He’d told me he wanted me, however much of myself I was willing to give. And I’d been willing to give it all, until I knelt in infected blood and had nothing left worth giving.

He must’ve had the vaccine by now. Mother would’ve seen to that. If it worked right, I could kiss him again without sentencing him to the long and silent ever after. But why take chances, especially when my own life might not extend past the New Year?

If possible, Ada was even more complicated.

“Look,” I said. “It’s for the best. He’ll—”

The door opened, and I turned. For a second, I thought Hank would walk through, smiling, in a slim waistcoat and a fine hat. Ready to take me in his arms, offer up absolution.

But that wasn’t the kind of day I was having.

Instead, an enormous woman in a blue dress and blue hat walked in. She had wrinkled brown skin and suspiciously pointy teeth. It was unnerving as hell when she smiled at me.

“Hello, Prince,” the Godmother said. “I’m calling in that favor.”

The Godmother was smart, ugly, and one of the most powerful women in the City. Once upon a time, she’d patched me up. I’d been hoping to drop dead before she cashed in on that debt.

I led her into the back office, poured myself a drink. “Didn’t know you ever left that can house you run. Whiskey?”

“Bit early for me,” the Godmother said, sitting as comfortably as she could in the narrow chair. “You look well, Prince. I feared otherwise, when I heard of your condition.”

I took a sip of my drink. No point asking where she’d heard—info, after all, was half her business. But not many people knew I was sick. Hell, my own mother didn’t know. “Why don’t you just cut to the chase, Godmother? What terrible thing do you want me to do?”

“My, so dramatic. You needn’t fret. I only want you to locate a beautiful woman. From what I remember, that’s something of a pastime.”

There was a muffled noise from the other side of the door. It sounded suspiciously like a snicker.

“One of your working girls?” I asked, glaring at the door.

“Actually, she runs some cheap gin mill downtown, been missing about a day. Name’s Rose Briar.”

The snickering stopped.

Last time I’d seen Rose, we’d been in that cheap gin mill, talking about the people I’d had killed there. To be fair, they had tried to whack me first, but it’d still been more murder than self-defense. Kept me up at night, sometimes. Probably not as often as it should have.

“You wouldn’t waste this favor on just any broad,” I said. “What do you really want Rose for?”

The Godmother smiled. “I only want to make sure nothing’s happened to the poor girl.” She fluttered her eyelashes innocently and laughed when I flinched.

I couldn’t take her word, of course, but I couldn’t look away, either. Rose was a friend and she was in trouble, one way or another. I’d just have to find her and go from there.

“I spot her,” I said, “and we’re square?”

The Godmother shook my hand. “Bring her to me, and I’ll strike you off the ledger for good.”

I left Jack at the office, digging up everything she could on Rose, while I popped over to her apartment, looking for a smoking gun, a secret diary. Any push in the right direction.

Instead, I found the same things you’d find at my own place: unpaid bills and dirty dishes. Nobody left good clues anymore.

The apartment didn’t look much different than it had five years ago. Clothes draped all over the place. Blues records stacked near the gramophone. Some furniture had been moved around but not recently. No ominous bloodstains beneath the rug.

I walked into her bedroom, rifled through her drawers. There was a framed picture on her bedside table: a black man lifting a black woman slightly off the sidewalk, swinging her around. They looked about 30, 35. Both laughing. The picture was slightly discolored with age, the woman’s dress and the man’s jacket twenty years out of style.

I traced their faces with my finger. Rose had only mentioned them once, when we’d stumbled into her apartment one night after drowning a bottle of rye together. “It cost them,” she’d said, staring through the ceiling with glazed, bloodshot eyes. “It cost them, but Christ, Jimmy. How they were bold.”

I never asked what the cost had been. That, I figured, I could work out on my own. Instead, I asked how long they’d been gone, but the hooch had turned my tongue to slush, so maybe she couldn’t understand me, or just didn’t want to. We’d never been the kind of people to willingly share ghosts.

There was nothing here. Frustrated, I walked back to the kitchen, glared down at the offensively normal dishes, the familiar stain of red lips around a whiskey tumbler. I picked up the glass—and then the one beside it, identical except the pink kiss left behind. The color was wrong. So was the shape: Rose had bee-stung lips, but a small, pert mouth. Her smile could only stretch so far.

“Now that,” I said, “is a proper clue.”

“What, you want me to clap? You’ve proved that Rose knows another skirt well enough to invite her for a drink. They’re called friends, Prince. Most people have them.”

“Could’ve been more than a friend,” I said, leaning into the phone booth when my legs started to ache. “Rose is…like me. Not real particular about parts.”

Jack’s dismissive noise was none too polite. “So maybe she’s got some kitten on the side. Who says the dame’s even involved? That cup could be a week old.”

“Kid, can’t you pretend to be supportive for once?”

“Maybe,” Jack said. “Have you come up with a better plan than walking around the Spindle, checking out every sister’s lips? Because you should know, some women switch shades. Some even take the day off entirely.”

That hadn’t been my exact plan. “I’m going to The Poisoned Apple,” I said. “And I’m not taking any grief from you until you’ve actually uncovered something juicy.”

“Give me time,” Jack said.

“Yeah, well. We only get so much.”

Jack took a breath, and I cursed. I hadn’t meant to say it like that—or anyway, I hadn’t meant to say it out loud—but there it was again, hanging between us. She thought I should go to my folks, ask them to fork over the kale, but I couldn’t, I couldn’t do that. Even if I could, I’d waited too long. My legs were going to give. How would I work? How would I live?

I tried to imagine it. Wheeling through the uneven streets. Scooting up stairs when the elevator broke down. Not able to reach things. Not able to dance. Hell, forget about taking a spin—I didn’t have the first idea how a paralyzed guy even took a piss.

I’d given up a lot, when I’d contracted the Pins. Now it wanted to take my legs too?

“Jimmy,” Jack said. Her voice sounded far away over the phone. “You can’t pick pride over your life.”

Maybe I could. I couldn’t pick it over Jack’s life—but she’d be okay, when I was gone, maybe even better off. She sure would’ve been if I’d given her that briefcase last December instead of spending it all on a lost cause. But I hadn’t been able to shake the fear, and I still couldn’t shake it now. To be gone. To be gone—

“I’ll call you when I know something,” I said, and hung up before I could say anything I’d regret, or cry.

I took a few minutes to put myself together before driving over to The Poisoned Apple. The joint was nearly empty, but I did recognize one friendly face behind the bar.

“Oh no,” Stanley said as I sat down. “Not you.”

“Stan, that hurts. Whiskey, neat.”

He hadn’t changed much in the past year. Hands still trembling, pale face flushed red from drink. A bit more white in his hair. Last time I’d seen him, he’d had good reason to be this nervous. I didn’t like what that might mean for Rose now.

“Looking for your boss,” I said.

“Haven’t seen her since yesterday.” Stanley poured himself a belt of hooch, larger than mine.

“Say where she was going?”

“Nope.”

He couldn’t hold my eyes. “Stan, all the dope you and Rose run here…how are you this bad of a liar?”

He ignored that. Tipped back his glass and tried to fix himself another. I reached over, grabbed his wrist. “Drink yourself stupid later. I want what I came for.”

Stanley tried to shake me off, but the booze had him off-balance and I wasn’t exactly known for letting things go. “Look, I liked Rose—”

“Liked?”

He cursed. “I don’t know, not really. But she loves this shithole. She wouldn’t skip out, unless she’s not coming back.”

I released his arm. “Maybe,” I said. “But I’m not gonna stop looking till I trip over a cold grave, so how about you stop wasting my time and tell me where she was headed?”

Stanley rubbed his arm, glaring at me. “All I know is, the boss was looking for her.”

I frowned. Rose owned The Poisoned Apple, so he must have meant the dope they slung on the side. “All right, who’s that?”

Stanley laughed. “You don’t know? You don’t know the Dragon?”

I didn’t really appreciate the scorn, not coming from a rheumy-eyed boozehound with bad breath. “Well, sure,” I said. “But you can’t mean—”

He nodded.

I stared at him. “Rose works for Moll Chen? Directly?”

Jesus.

I’d never met Moll or knew anyone who had, but I’d heard of her, of course. Everyone had. Half Irish, half Chinese, and all scary—Moll Chen was the boss of bosses. She ran it all—smack, nose candy, the big O—and only fools and head cases tried to double-cross her. Presumably, they called her the Dragon because she was Chinese and the street wasn’t real creative, but also because Moll had a tendency to set anyone who’d offended her on fire. Not someone I was eager to meet.

I’d seen Rose crunching the numbers on the bindles in this place, but I figured she worked for someone who worked for someone who’d once eaten at the same restaurant as the Dragon. If Moll had been looking for her…well, Stanley was right to be all worked up.

The Dragon’s not-so-secret hideout was a goon-infested lounge that doubled as an opium den in Chinatown. “A trip to the Fox & Tiger,” I muttered. “That will make this day better.”

Stanley shifted. Suspiciously.

“Stan?”

He fumbled for the whiskey again, and I grabbed it first, held it away from him. “Something you’d like to share?”

“Come on, man. They’ll kill me.”

“Who says I won’t?” I wouldn’t, but Stanley didn’t know that. After all, last time I’d come around, I’d ordered two executions about six feet from where he was standing.

“They’ll kill me worse,” Stanley said.

I leaned back in my chair, far enough to flash the gat at my side. “True. But tell me what I wanna hear, and you still got options. A dead man don’t got shit.”

I finished my drink. Smiled.

Stanley groaned and buried his head in his hands.

Turned out, the Fox & Tiger was only a smokescreen for bulls, and the woman who ran it wasn’t Moll Chen; hell, she wasn’t even Chinese. The real Moll Chen operated out of St. Katherine’s Hospital under the name Molly Chang.

St. Katherine’s was halfway across the city. I hesitated when I arrived, glancing at a nearby pay phone. I’d promised Jack updates; then again, I knew what she’d say, that I should turn heel and run. Frankly, I was half-inclined to agree—I wasn’t real keen on getting rubbed out by fire. It was a bad way to go, and it haunted my sleep: dreams where the Burning Days never ended, where the bulls still came for anyone who even looked sick. Dreams where they dragged my best friend, Tommy, away, where Mother couldn’t find him before they lit the fuse. Dreams that weren’t dreams at all.

I should’ve done a better job hiding Tommy. Should’ve fought harder, when they took him away.

I squared my shoulders and walked inside, ignoring the butterflies in my belly and the pins and needles in my legs. Not a good time, I told them, like my failing body gave a damn what I thought.

I didn’t run straight for the source. Figured a place like this might be a handy spot to hide someone, assuming you were in charge of all the needles. I made a quick search of it, peeking in rooms and chatting up nurses to see about any young black patients. I couldn’t help but notice that a number of the staff looked rough, especially around the intensive ward. One tall, heavy nurse had a black eye and two fingers taped together in a splint. Another woman—shorter, thinner, but with the same fair skin and perfect dimples—moved with a noticeable limp.

“She’s about 5’5”,” I told Damian, a good-looking Asian orderly with unbelievably cut arms and an ugly scratch over his eye. “Maybe 160, 170 pounds. Damn pretty.”

“Haven’t seen her,” Damian said. “But I’ve never been one to notice skirts. Pretty suits, now . . .”

I laughed. “Sorry,” I said. “Taken.” Too bad, though, because Christ, those arms.

Damian shrugged, and then froze up, seeing something behind me. “Molly—”

“I’ll take care of the gentleman, Mr. Doan.”

Damian winced at me, almost sympathetically, and walked away. I turned around, coming face to face with…well, nobody. The nurse couldn’t have been an inch over five-foot, which meant she didn’t even hit my shoulder. I put her at about 60, based on the lines in her forehead, which deepened into furrows as she raised distinctly unimpressed eyebrows. A smattering of unlikely red freckles stood out against her sandy beige skin. Thin lips. No lipstick.

I took a breath. “Moll Chen, I presume?”

Moll inclined her head. “Thank you.”

“For recognizing you?”

“For your fear. Even when the Dragon turns out to be an old woman, it’s apparent in your throat, your white knuckles. How you glanced to make sure of your exits.”

“Yeah,” I said sourly. “Happy to oblige.”

“Don’t be sullen,” Moll said. “It shows good sense. I’m too busy to waste time with fools. Come this way.”

Reluctantly, I followed her to a patient’s bedside. He was a middle-aged white man, muttering incoherently about monsters. Moll took his pulse and tipped his head to the side. Blood was dripping out of one ear.

“Nothing to be done,” Moll said. “He should die very soon, hopefully.”

I lit a gasper. “Is that mercy I detect? Or do you just need the bed?”

There went those eyebrows again. “You speak as though mercy and practicality are mutually exclusive. I assure you, they are not. I am as merciful as I can afford to be, Mr. Prince.”

I wasn’t real crazy that she knew my name when I purposefully hadn’t given it to anyone. Still, I followed her as she moved briskly on to the next patient. “Suppose we cut to the chase,” I said. “Word on the street is that you were looking for Rose Briar yesterday.”

Moll stuck a thermometer in the patient’s ear. “This word is true. Is she dead?”

“Missing,” I said, watching her carefully. Moll was hard to read, mostly because she went through her routine like I wasn’t even there: taking out the thermometer, nodding at it, laying a cool cloth on the man’s head. “What did you two discuss?”

“Ingratitude.”

“Care to be more specific?”

“No,” Moll said. “I do not.”

“Okay. How about you tell me how the conversation ended? Was kerosene involved?”

Moll smiled. “It is a rumor,” she said, “that I burn all my enemies alive. It is only necessary to do this a few times before a sufficient reputation is formed.”

I didn’t have a particularly witty response to that. “So, Rose is your enemy?”

Moll moved onto the next patient, grabbing a handful of syringes along the way. I kept what I felt was an appropriate distance. “She disappointed me,” Moll said. “But she left this hospital alive. Our conversation was interrupted.”

“By what?”

I heard something gurgling behind me and followed Moll as she walked back to the first patient. His whole body shuddered as he choked on nothing. More blood spurted out of his ears.

“Karen,” he whispered, and died.

My legs felt numb, and I wasn’t sure if it was the Needles or that cold panic in my stomach again, spreading down. This was how I was going to die, assuming Moll didn’t bump me off first: paralyzed and delirious in some hospital bed, calling for someone who wouldn’t be around. Because why would he be? That’s why I’d left him, after all, so he could have a real future and I could have…this.

I didn’t want this.

I looked up at Moll. She was studying me, still holding her syringe. “Everybody dies alone,” she said. “But some more so than others. Tell me, Mr. Prince: did you tell anyone you were coming here?”

I opened my mouth. But I didn’t get the chance to answer.

“Probably not,” a voice said. “Common sense isn’t really one of Jimmy’s strengths.”

So much for a real future.

“Hank?”

And Hank Delgado walked into the room.

It’d been two months since I’d last seen him, though longer since we’d spoken. He’d grown a sliver of a mustache—elegantly trimmed, of course—but otherwise looked the same, slender and stylish, wearing a light grey suit tailored immaculately to his calves, thighs, and backside. Especially backside. Bronze skin and silver specs and a ready-made smile, like he’d been born slightly amused by the change of scenery from womb to world, and every passing day just made the joke that much funnier. But the smile went taut as he glanced at me.

“On the other hand,” Hank said. “I made sure to leave several messages regarding my whereabouts, and instructions on who to blame should I not return. Perhaps you’ve heard of my employer, Evelyn Prince? Or the lovely Ms. Ada Singh? Regretfully, they’re fond of Jimmy too, and I doubt they’d take it well, if he or I were to suddenly disappear.”

Moll inclined her head. “No. I’m sure they would not, Mr…?”

“Delgado.”

“Your precautions are unnecessary, Mr. Delgado, but they do you credit. You may take your unwise friend home with you now.” Moll pulled the white sheet over the dead man and looked at me. “I hope you find Ms. Briar soon, Mr. Prince. I’d like to finish my conversation with her.”

She twirled the syringe in her hand.

I took that as my cue.

Once we were outside, I started heading for my car, only to have Hank grab my wrist and all but drag me to his. It wasn’t a big loss, since my heap barely had four functioning wheels and Hank’s Buick was a thing of beauty, but it did mean I’d have to return to St. Katherine’s eventually.

We turned out onto the main road. “Silent Night” came on the radio, and I turned it off. Hank flipped it right back on. Hank didn’t like Christmas music anymore than I did.

“So,” I said, after a long silence. “How’d you find me?”

“Jack got antsy. Knew you were headed to The Poisoned Apple, so she shook down that bartender until he spilled the beans. Then she rang me.”

I nodded. “Thanks.”

Hank snorted. “Thanks, he says. Well, you’re welcome, Jimmy. I’m always happy to help con cualquier mierda en que te metas.”

I raised my eyebrows. “So, you’re still mad, then.”

Hank grinned, hard, and it didn’t look right on him. “It’s no wonder you became a detective,” he said. “Skills like that.”

I leaned back, watching him. He looked vaguely green around the gills, and his fingers were tight around the steering wheel. Nerves, maybe—or maybe he was just that sore. Long as I’d known him, I’d never really seen Hank angry before.

“You look good,” I said, because I never did know when to keep my mouth shut.

“You look like shit. You even taking your pills?”

“Sure,” I said. It wasn’t exactly a lie. “Otherwise, you’d have found me in the cooler, not the sick house.”

“You taking them every day?”

“What are you, my mother?”

“No, Jimmy. Evelyn doesn’t know to ask those questions because you don’t have the decency to tell her, and I, for God knows what reason, am keeping your lousy secret. So, let me ask again: are you actually taking your pills?”

I pulled back, stung. “You saying you still care?”

Hank hit the brakes, right there in the middle of the road.

Tires screeched behind us, followed by a string of Vietnamese cursing. “Jesus, Hank—”

Hank blinked and hit the gas again, taking a hard right into a narrow alley. He threw the car into park. “Listen,” he snapped, so I did: three minutes straight of violent and presumably creative Spanish. I waited for him to draw breath.

“Okay,” I said. “I got pendejo, pinche cabron, and I’m pretty sure you suggested I had an unnatural proclivity for farm animals.”

Hank narrowed his eyes at me. “Chickens.”

“Well, I figured it was that or sheep.”

“You didn’t know either a year ago.”

“Yeah, well.” I shrugged uncomfortably. “Maybe I’ve been studying.”

He stared at me and then, almost helplessly, started to laugh, tipping his head backwards and closing his eyes. “You—you told me you were dying in a note you shoved under my door two days before Christmas, breaking up with me for ‘my own good’…and now you start learning Spanish?”

Hank rolled his head to the side. His eyes were wet, but his smile was more natural, less like a wounded cat baring its teeth.

I shrugged. I couldn’t very well say that I’d been trying to hold onto pieces of him, like that would somehow make up for the whole. “You wanna yell at me some more?”

“Always.” But he didn’t, just started the car again and reversed until he was back on the main road. I realized we weren’t heading back to the office.

“Hank… ”

“Relax,” Hank said. “I’m not taking you to your parents’ house—”

“Good.”

“Just to your fiancée’s.”

Well, shit.

Ten months ago, Mother introduced me to another one of her high society marriageable dames at one of her many fundraisers. I hadn’t wanted to go, hadn’t wanted to make small talk with some fancy skirt looking for a rock to slide on her finger, no matter how bizarrely insistent Mother was that I’d like this skirt for once—but I’d been having this uncomfortable feeling lurking somewhere around my ribs all year, whenever I thought I might disappoint her. Since I’d spent most of my life actively trying to disappoint my folks, this newfound sense of shame was unnerving.

I’d expecting to suffer through a few dances, make nice with a silly sister or two…and then, Ada.

Ada wasn’t at all the woman I’d expected her to be.

Hank pulled up in front of her house. The Tremaine Manor, back when Old Lady Tremaine was still alive, keeping Ella locked away in her own cellar. “Don’t suppose you’re coming in?”

Hank shook his head. “Have to pick up Evelyn first.”

“Dinner’s not till seven.”

“Yeah, but she has opinions on the seating arrangements.”

Of course she did. I hesitated, fingers around the door handle. “I’m glad Jack called you.”

“The future Mrs. Prince would’ve been better backup.”

No one’s better backup, I didn’t say. “Jack may have been playing matchmaker. She thinks I made a mistake.”

“You did,” Hank said quietly.

I opened my mouth—and then closed it, stepping out of the car. I bent down, looking at him through the window. “I meant what I said before. Thanks for—for coming.”

“Jimmy. I’ll always come.”

“You don’t have to.”

Hank snorted. “Right,” he said, and drove away.

I watched the car until I couldn’t see it anymore and then turned and walked to the door. I felt lousy, and it wasn’t just the guilt weighing me down, though that was heavy enough. My skin felt hot and thin, spread tight across my bones. Considering all the snow around, that wasn’t a great sign.

A harried maid led me into the parlor, empty but for a handful of servants bustling in and out. I heard quiet footsteps behind me, a gift. If she hadn’t wanted me to, I never would have heard her. “Think it’s too late to cancel?”

“I was having the same thought.”

I turned, grinning. “Cold feet, pumpkin?”

“Please stop calling me that.”

“I always get confused, how to best address you. You have so many little monikers.”

“For present, Ada will do.”

I bowed. “Ada it is.”

Ada curtsied back, sardonic as ever. She was stunningly beautiful, tall and lean with gams so long they could probably wrap around me twice. Her hair was black and gently curled, spilling just past her copper brown shoulders. “Will you sit?”

“Sure.” But my body betrayed me before I could make it, legs abruptly cutting out from under me. I landed hard on the floor, too warm and vaguely dizzy. “Well, hell.”

Ada knelt beside me, a hand to my forehead. “Anyone tell you you’re an idiot?”

“You mean, today?”

She shook her head and stood up, walking to the phone. “Jack? It’s Ada. I’m glad I caught you. Jim has apparently forgotten to take his medicine. Yes. Yes. Jack, I don’t disagree on any particular point, but could you snag his pills before—thank you. I’ll see you soon.”

She hung up and sat beside me. “Real ladies don’t sit on the floor,” I said. “Wouldn’t want anyone to get suspicious.”

She didn’t move. “You look terrible.”

“You look tired.” There were faint purple shadows under her eyes I hadn’t noticed before. “What’s eating you?”

“My betrothed is a head case.”

“You knew that when you proposed.”

“True.” Ada rubbed her eyes. “It’s a lot to adjust to, all this.” She waved a hand at all the finery: ugly artwork and furniture that someone somewhere had decreed valuable. “It’s what I wanted, or told myself I wanted. What I dreamt about. Reclaiming the life that was stolen from me—but none of it feels like mine. The bed is too soft. There are too many windows. I’ve been going to the cellar lately, just to sleep.”

Well, that didn’t sound particularly healthy. Then again, I was hardly the picture of emotional health myself. “Dreams change,” I told her. “They have to. Stretch with our bones as we grow up. No shame in ending up on a different path than you started down on.”

Ada picked at the carpet, eyes low. “Maybe I miss the path that was chosen for me.”

“You mean…the one with all the dropped bodies?”

“With all the bodies I dropped, yes. Sometimes I miss the work.” She did look up at me then, eyes troubled, but voice steady. “Maybe we’re both a couple of head cases.”

“Good thing we’re getting hitched then.” She laughed, and I took her hand. “El— ”

A valet sped through the room, and she squeezed my fingers. “Pretty sure we discussed my little monikers.”

I ignored this. “Ella,” I said, once the valet had left. “I can’t judge your choices. I won’t. Not after you saved my bacon. Not after the choices I’ve made.”

Ella frowned. “I met Thom once. You made the right call with him, with Patricia White, after everything with Snow—”

“More blood on my hands than that.” Unsteadily, I pushed myself up. My legs were shaky but held me, long enough that I could reach the plum sofa and drop down. “Of course, last I checked, marrying me was the third step in cementing societal credibility, so if you’re planning to retreat for a life of crime, best break my heart before everyone shows up to eat.”

“Can’t break a heart that doesn’t belong to me,” Ella said.

I groaned. “Not you too,” I said, just as the doorbell rang. Too soon to be Jack.

“It’s Jack,” Ella said, looking out the window and very, very still. “Maybe her friend drove her.”

“Who’s that?”

“I can’t quite—”

The butler appeared. “A Ms. Jack and Mr. Nguyen to see you, madam.”

“Nguyen?” Ella and I asked, and glanced at each other. The butler left, and I whispered, “You know Nguyen, you knew Mr. Almonds. Are there conventions for button men or something?”

Jack and Nguyen walked in before she could respond. Last time I’d seen him, Nguyen had a broken nose, a lame leg, and the shakes, courtesy of either shellshock or being on the run. He looked better now: nose mostly straight, limp all but gone, dark hair grown out from an uneven regulation cut. His fingers weren’t trembling, either; more importantly, they weren’t wrapped around a gun. We hadn’t left on unfriendly terms, but that didn’t mean we were friends.

Not that Jack was looking too friendly herself, as she chucked the bottle of pills at my head.

I caught them, but barely. “Hey to you too, kid,” I said, dry-swallowing a couple. “Nguyen, always a pleasure, but what the hell you doing here?”

“I called him,” Jack said. “Figured if you’re gonna go pissing off drug lords, we’ll need all the backup we can get.”

“How do you know I pissed Moll off?”

“Opened your mouth, didn’t you?”

“Hey—”

“Squabble later,” Nguyen said, sitting beside me. “Last I heard some dame still needs help.”

Right. Nguyen had never actually met Rose.

I cleared my throat and turned to Ella. “Let me catch you up on the case,” I said, and told her the shorthand: who Rose was, the Godmother’s interest, the visit to St. Katherine’s. “Jack? Dig up anything worth adding?”

Jack, typically, had shunned the desk chair in favor of the desk. “When have I ever let you down?”

“You’re still wearing that Santa hat.”

Jack didn’t stick out her tongue or flip me off, so I knew she was still fuming. “A few years after the Burning Days, Rose’s folks were murdered, bodies discovered in some alley. What was left of them, anyway.”

It is only necessary to do this a few times before a sufficient reputation is formed.

I swallowed, feeling a little sick. “They were burned alive, weren’t they?”

Jack nodded.

Two decades of slamming back eel juice like water, and I still couldn’t forget the smell of burning flesh. Rose was only a couple of years younger than me. She’d remember it, too.

“Why did Moll kill them?”

“Officially, dunno. Case went unsolved. But word is that the Briars got their hands on a stash of nose candy and distributed it without cutting Moll Chen in on the cabbage.”

“It cost them, but Christ, Jimmy. How they were bold.”

I whistled. “Not inviting the Dragon to the party? That’s bold, all right.”

Nguyen snorted. “It’s stupid.”

It was probably both. I shook out a gasper, and then another when Ella held out a hand. “Where’d Rose end up?”

“Adopted. Couple of sisters, Florence and Fanny Merring. Nurses, both of them. Guess where they work?”

I didn’t have to. I was pretty sure I’d seen them and their dimples earlier today. “So, Moll kept Rose prisoner?”

“Indentured servitude, probably,” Nguyen said. “Work off her parents’ debts, or die trying.”

Ella, I noticed, was staring at the carpet, her long, lovely fingers closed into fists. I thought about offering my hand, but wasn’t sure she’d take it. Instead, I offered another, less crumpled cigarette.

She accepted it gratefully, putting the first one out in the ashtray. I stared at her gasper, and then back up at Ella. For a long moment, I lost track of the conversation.

“—If Rose wanted revenge, she took her time about it.”

I blinked, looking at Nguyen. He hadn’t noticed my little trance, and neither had Ella. Jack sure had, though.

“Vengeance doesn’t come with a clock,” Ella said. And she’d know. Ella had killed both her stepsisters, possibly her stepmother, too. No way of knowing how many people she’d bumped off, or how many secrets she was hiding. You could never be sure with a dame like that.

But apparently I had been sure. Otherwise, I’d have thought to look at her lips, too.

“Prince?” Ella’s smile was lovely and wide. “Solving the case over there?”

I laughed. “Just thinking through the angles. Why was Moll looking for Rose? How does the Godmother fit into this?”

“Will you tell the Godmother?” Ella asked, leaning forward. “If you find Rose?”

“I don’t know.” I met her eyes. “It’s hard to trust anyone these days.”

Ella opened her mouth, but one of the maids came in to ask about flower arrangements. “Sure you guys shouldn’t cancel?” Jack asked, as soon as the maid was gone. “Lot going on right now without adding wedding nonsense to the insanity.”

Nguyen blinked at me. “You’re getting married? She agreed to marry you?”

“Hey,” I said. “I’m a catch.” I wasn’t—my mug was decent enough, my family influential, but my business was an embarrassment and my illness a secret horror. I desperately wanted to skip the dinner, but now I couldn’t afford to. Ella and her painted kiss were the best lead I had to go on.

Ella shook her head. “Evelyn says it’s the quickest way to get caught, freezing up when things get hairy. Speaking of your mother, Prince—”

“Must we?”

“—I could use a favor. I’m told she has opinions on accessories, and I’m worried none of my current collection will do. Some time ago, I stashed away a package of…souvenirs, a few baubles, some nice rocks. But I can’t leave with all these people running around.”

“Anything for you, pumpkin. Got an address?”

She wrote it down. “Nguyen,” I said, “why don’t you stay while Jack and I grab these? You two can catch up. See who’s iced the most folk.”

Ella frowned. “We’re not exactly old friends. Crossed paths on a job once.”

“She broke three of my ribs and knocked me out.”

Ella shrugged. “You were in my way.”

“You and Nguyen go,” Jack said. “I’ll stick around, see if I can taste test the dessert or something.”

That was exactly the opposite of what I wanted. “You sure?” I asked. “You could throw stuff at the protestors.”

“Tempting, but I’ll hang back, as long as your dame can restrain any urges to doll me up. No dresses. No blush.” She looked at me. “No lipstick.”

So, she had put it together. I wasn’t surprised, and I understood what she wanted. Leave her behind to snoop. Trust her to take care of herself. Treat her like the partner she was, not the secretary she’d started out as.

We all end up on different paths.

I nodded, even though my stomach clenched up and the space in my lungs felt a little tighter. I did trust Jack. I just loved her, too.

Funny, how I was always making that same mistake.

I drummed my fingernails restlessly against the windowpane. Tap. Tap tap tap. Tap. Tap tap—

“You gonna tell me what’s going on,” Nguyen asked, turning down a crooked little street. “Or you want me to guess?”

“Guess,” I said, just to be contrary.

He sighed. “Tell me what the hell’s going on, Prince.”

I tapped my fingernails some more. “Rose’s apartment,” I said finally. “Someone left a kiss behind. Ella, apparently, except they don’t know each other.”

“So she says.”

I had one hell of a headache. “Yeah.”

“Maybe she’s stepping out on you?”

If only. “Ella can step wherever she wants.” I didn’t think she went for skirts, but it wouldn’t matter if she did. Our arrangement wasn’t exactly exclusive. Couldn’t even call it romantic, really: I carried a torch for her, maybe always would, but my heart, well, it belonged to someone else—as everyone was so damn keen to point out today. “She’s involved somehow.”

“Somehow? She’s a hatchet man, Prince.”

“Not anymore.”

“You sure? It’s not an easy line of work to get out of, especially if you develop a taste for it.”

And Ella had admitted as much. “You like it? The work?”

“No,” Nguyen said, after a moment. “But I don’t have a problem doing it, either.”

I saw the tremor in his left hand. Left it alone. “You’re right,” I said reluctantly. “Most likely, someone hired Ella to kill Rose, and Rose is…”

I didn’t say it. Stupid not to, but sometimes you couldn’t help yourself.

Nguyen took pity on me. “So who hired her?”

I frowned, thinking it over. “A while ago, Ella had to flee Spindle City. Went to the Godmother for help. Might be I’m not the only one with a debt.”

Nguyen turned down another narrow alley and parked on the curb. “So, the Godmother hires you to draw Rose out, and Ella to drop her when she does?”

“Maybe,” I said, and got out of the car. The Pond was a rink-a-dink gin mill, long since abandoned, with broken windows and dust-coated floors. I warily followed Nguyen inside, hand on my gat, but there was no one there.

Ella told us she’d stashed her jewels behind the bar, underneath the floorboards. Nguyen got to work, prying them up, and I knelt beside him, exhausted. My legs were steadier and my fever had gone down, but I felt weary down to the bone. Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad, not being able to walk. Walking was exhausting. Everything was exhausting.

Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad, not waking up. The world was ugly and treacherous, and at least I wouldn’t be afraid all the damn time.

“Nguyen? You know what the hell you’re living for?”

Nguyen’s small hands went still. “No,” he said finally. “But I plan to keep going until I figure it out.”

I nodded. “Yeah.”

Nguyen went back to work, and the board came loose. He reached down and pulled out a black briefcase, handing it to me. Ella had given us the combination, and I opened it carefully, half expecting it to blow. But all I saw were trinkets: a few diamond rings, some ruby earrings.

Could be she just wanted the glitter.

Or maybe she wanted me out of the way.

Or maybe, I thought, as I felt for and found a false bottom, she needs something else from here.

I pulled out a brown leather journal and opened it, flipping through pages of names and numbers, of sins and debts.

“A diary?”

“A ledger,” I said, scanning through the names: bulls, politicians, mobsters, clergymen. Assassins who’d needed help skipping town. Private dicks with complicated love lives.

Bring her to me, and I’ll strike you off the ledger for good.

“It’s the Godmother’s,” I said, hushed.

Nguyen and I stared at each other for a beat before I looked back at the book. One page alone was a scoop worth killing for: the mayor pushing lobbies to keep his illegitimate tots out of the press, the DA with the stiff fetish, the rich skirt who needed help disappearing her brother’s body. These were the kind of secrets that people bled both green and red to protect, secrets you were supposed to carry with you to the grave. If this book ever saw the light of day, half the town could end up in the clink, or worse.

So what the hell was it doing here? Had Ella stashed it for the Godmother, or were we stealing it from the Godmother? What the hell had I stumbled into?

Nguyen wasn’t waiting to find out. He pulled me up and dragged me to the car, iron in hand. I kept an eye out, but no one stopped us from burning rubber, and I couldn’t spot a tail.

We passed a payphone. “Stop,” I said, but he didn’t, not for several blocks. When he finally did pull over, I jumped out, only to be swarmed by rabid protestors. One shoved a pamphlet in my face. “Only the Lord decides who’s worthy of being healed.”

“Move,” I said, “or I’ll spit on you.”

He must not have been worthy, because he jumped away fast. I shut myself in the phone booth and called Ella.

She answered quickly. “What’s wrong?”

Everything. “Nothing,” I lied. “Just thought you might want the update: case safe and secure. Talk to Jack?”

“Sorry,” Ella said. “She’s indisposed, I’m afraid.”

Maybe my heart stopped for a second there. Then it started again, beating harder than ever.

“Want me to pass on a message?”

I coughed. “No,” I said, voice as even as I could make it. “No, that’s all right. I’ll be back soon enough.”

I hung up and returned to the car. “Jack couldn’t come to the phone,” I said dully, eyes closed. “I think—”

“We don’t know anything yet,” Nguyen said.

No. We didn’t. But I couldn’t get past the sick feeling in my gut, that I’d made a horrible mistake, leaving Jack behind. If Ella had hurt her, if she’d killed —

“Drive,” I said, and Nguyen drove.

It was starting to get dark, by the time we got back to the manor. Nguyen parked a half-mile out and rummaged in his trunk for supplies. There were fresh tire tracks in the snow nearby, but I didn’t have time to puzzle out where they’d come from. “Don’t suppose you’ve got binoculars?”

Nguyen frowned. “Of course I do.”

Armed with binoculars, iron, and extra clips, we snuck onto the property. I introduced Nguyen to my most sophisticated investigative techniques: climbing trees and praying for a good view. All I got was déjà vu and a quickly sinking heart.

Hank’s car was parked outside, and sure enough, I spotted him and my mother sitting in the parlor, backs to the window. If they were injured, I couldn’t tell. Ella was sitting nearby, mouth moving. Jack wasn’t in the room.

I looked through every open window I could find, but I couldn’t spot her anywhere. Not every room was visible, though. Couldn’t peek into the attic. Couldn’t see into the cellar.

I needed to see in that cellar.

I climbed back down the tree. “Okay,” I said. “I’m going through the basement. You go around the back, see if you can sneak Mother and Hank out of there somehow. Jack, too, if you spot her. Take Hank’s ride. I’ll take yours, and we’ll meet up at my place.”

Nguyen stared at me. “That’s a terrible plan.”

“You have a better one?”

Nguyen didn’t, so we went with mine.

I crept carefully to the small cellar window. Brambles had grown, wild and thorny, around the bottom of the house, but none blocked the glass. They’d been cut, deliberately. And the window, too grimy to see through, was slightly ajar.

Holding my breath, I pushed it open, leaned in—and promptly fell through. “Jesus Christ,” I whispered, blinking in disbelief, but my eyes hadn’t deceived me.

It was Rose.

She was lying on Ella’s old cot, and in the dim lighting, looked absolutely terrible—dark skin nearly ashen and beaded over with sweat. She didn’t seem injured, other than an angry needle mark on her arm, surrounded by a black bruise, but when I took her by the shoulders, she didn’t respond at all.

“Shit,” I muttered, with feeling. How the hell was I going to get Rose out of here? It was hard enough lifting myself through the window, never mind an unconscious woman. And I seriously doubted I could sneak her up the stairs without anyone noticing. Frankly, I was a little surprised no one had come when I’d fallen inside.

This time, I didn’t hear her footsteps. Guess she wasn’t in a giving mood. I only briefly felt her hands before I was thrown hard into a wall.

“Fuck,” I swore eloquently, as I tried and failed to push myself back up. Blood trickled down from my temple where I’d cracked it against the uneven brick, and I couldn’t bring my arms up in time to stop the knife at my throat—but the hand holding it paused, anyway.

“Prince?”

I blinked. Ella knelt in front of me, eyes wide. She’d changed into a pink saree while I was gone. “Knife doesn’t go with the glad rags,” I said carefully. “And I’d hate to ruin all that silk with my poisonous blood.”

Ella drew the blade back, but not enough for comfort. “Why can’t you ever let anything go?”

“Born stubborn, I guess. Mother always says so. While we’re on the subject, why don’t you let her and Hank go? No need for them to get hurt.”

She frowned at me. “I haven’t—”

“And Jack? I suppose she’s fine too?”

“Prince—Jim, you’ve got this all—”

Ella turned suddenly, and I followed her gaze. Nguyen stood at the top of the stairs, roscoe aimed at Ella’s head.

“Back away from him,” Nguyen said. “Now.”

Ella did, dropping the knife. Nguyen slowly walked down, gun steady. From further upstairs, I heard voices: Mother’s, Hank’s, Ja —

I used the wall to push myself up. “Jack!”

Jack appeared in the doorway, Santa hat and all. She didn’t appear hurt; actually, she was almost bouncing, although the grin dropped from her face when she saw me. “Shit, Prince, are you—Rose! I knew it! I knew you saved her, Ella!”

“Wait,” I said. “What?”

Hank and Mother pushed their way in behind Jack. Mother took in the whole scene: an injured son, an unconscious woman, a gun pointed at her future daughter-in-law. She said, “Jimmy, I hope that’s not what you planned to wear tonight.”

I slumped to the ground, laughing. Hank joined in, then Ella and Jack. Nguyen didn’t because he was a humorless bastard, but he did cautiously lower his gun.

“When you’re all done,” he said. “We have some things to hash out.”

The least suspicious way to cancel a rehearsal dinner, Mother said, was to stage a loud lover’s quarrel. Ella slapped me before tearfully sending her servants away. Her fake tears were awful. The slap, unfortunately, was much more convincing.

The cellar was far too cramped for seven people, so we retired to the parlor, relocating Rose to the sofa. Ella sat by her side, occasionally wiping her forehead with a damp cloth. “Moll overdosed her with something,” Ella said. “She hasn’t woken since yesterday. I thought she was about to this morning, but . . .” Ella looked at Jack. “How did you know?”

Jack shrugged. “Stayed behind to snoop,” she said unapologetically. “Faked a trip to the ladies’ and found some interesting laundry in the trash: nurse’s uniform, hat, and face mask, all torn up and spattered with dried blood. Prince said the staff at St. Katherine’s looked beat to hell, and Moll said her conversation with Rose had been interrupted.”

“You were her backup,” I said.

“Against her wishes, yes.”

I frowned. “Didn’t want your help?”

“Said the briefcase was more important.”

“Over her life?”

“It’s hard,” Hank said dryly. “Loving someone with such a lousy sense of priorities.”

I glared at him. Might have thrown something, too, if Mother wasn’t around. “So then you didn’t steal it, the Godmother’s ledger. It was Rose’s errand. She stole it.”

Hank gaped. “You have the Godmother’s ledger? There’s an actual ledger?”

I pulled the book out of my jacket and tossed it over, amused when Mother scrambled up to read over Hank’s shoulder. “It’s why the Godmother came to me in the first place,” I said. “But how Rose got her hands on it . . .”

“Inside job,” Nguyen said. “Had to be.”

Seemed incredible, Rose working for both the Godmother and Moll Chen. But it would explain how the Godmother knew I was sick. Jack didn’t tell her. Hank hadn’t even told Mother, but Rose had felt my fevered cheek last year.

Ella kissed Rose on the forehead. “Moll treated Rose like a thing,” she said. “Thought she owned her. But Rose—”

“Rose doesn’t really take to being owned.”

I stood up too fast and caught myself on the armrest. No one noticed, too busy staring at Rose, whose eyes were half-open and glassy. She waved weakly at me, and then looked at Ella.

“So,” Rose said, lip-twitching. “Maybe you were right about that backup.”

Ella took a deep breath. “You—”

“Later,” I said. “Rose, glad to see you up and kicking. How about you try flapping your lips now, see what they say about the Godmother.”

Rose grinned. “It’s always information with you,” she said, and struggled to sit up with Ella’s help. “The Godmother came to me when I was 16. Heard about my predicament, offered me an opportunity. Spy on the Dragon, and when the time was right, she’d help me take Moll down.”

“You’re, what?” Nguyen asked. “25, 26?”

“29,” Rose said. “And yeah, the time was never right.”

“So you took the ledger,” I said. “As leverage.”

Rose shrugged one shoulder. “I like the Godmother,” she said. “Decent to her people, never set anyone on fire. But I couldn’t trust her word, and anyway, she thinks she has some claim to me, just like Moll does. And no one, no one owns me.”

Jack nodded, kicking her legs in the air. “But something went wrong. Moll found out.”

“Bad luck,” Rose said, slumping against Ella. Her full face was lined in exhaustion, like she could sleep another hundred years without waking up. “Stanley. Saw more than he was supposed to see, started acting shifty. People noticed.”

And when they did, he probably ratted her out to save his own skin, the little weasel. It did raise the question, though: what the hell did I do with her now?

Ella read my face. “You can’t turn her over to the Godmother.”

“No shit, pumpkin.” I stared at her. “Is that why you sewed your lips? You think I just hand people over for the noose?”

Jack and Hank both coughed, while Nguyen raised an eyebrow.

“Fine. If they try to bump me off first, yeah, I’ll let em get cut down, but Jesus Christ, Ella. Rose is my friend.”

Rose grinned wearily. “Aw, I like you too, Prince.”

“Shut up, Rose.”

My head ached like crazy. I rubbed my temples, fingers coming away a little red. Needed to apply some kind of bandage before —

But Mother was up, a silk handkerchief in her hand. “Here,” she said, reaching for me. “Darling, put this—”

“Don’t,” I said, jerking away fast, too fast.

Mother paused. A few years ago, I doubt I could’ve read the hurt in her eyes. “For Heaven’s sake, Jimmy, don’t . . .”

I looked up at her. Held my breath.

She knew it then, and didn’t want to. “Jimmy?”

I looked away. “Listen—”

“When?”

“It doesn’t—”

“When?”

I swallowed. “About a year.”

The room was deathly quiet. I didn’t want to look at any of them. Didn’t want to say, I’m dead by New Years, and if I live, I won’t keep my legs. But maybe Mother had been right a year ago: you have to face your ugly truths eventually. And I’d been running from mine for about as long as I could remember.

I forced myself to look at Mother, just in time to see her get shot.

The bullet struck her in the shoulder, and it happened so fast I barely registered the sound of shattering glass or Hank yelling. I caught her and Nguyen tackled us both to the ground, while Ella sprinted past, making a beeline for the basement. Bullets followed in her wake, and one clipped her across the back. Blood burst, and she dropped out of sight down the stairs.

“Ella!”

Rose’s voice, somewhere behind me. I glanced over my shoulder and saw her crumpled on her side, lying in front of the couch. Rolled off it, maybe, when the shooting started. She wasn’t bleeding, at least.

I quickly looked around the room. What used to be the window was now just a large, useless rectangle cut into the wall. Hank was lying on his back underneath it, shards of glass all around him. Breathing heavily, but he didn’t seem hurt, either. There was a gun in each hand.

Jack—Jack was—I didn’t see Jack.

“Jack? Jack?”

“Up here.”

I looked up. Somehow, Jack had scrambled up a tall bookshelf, knees drawn to her chest, carefully balanced above everyone’s line of sight. Despite myself, I started laughing.

“Kid,” I said. “There’s something wrong with you.”

“Yeah,” she said, shaking. “I’m about to get killed because some broad stole a book.”

Rose ignored that, or didn’t hear. “Ella!”

Nothing. I pushed myself up, only for Nguyen to shove me back down as more gunfire erupted. “Stay low,” he said and scuttled away, not towards the basement but the front door.

I looked at Mother. Her face was white with shock, but she was conscious, one hand over her bleeding arm. “Keep pressure on it,” I said, swallowing. “You’re okay. You’ll be okay.”

More gunshots, this time from the front door. I drew my own gat, six slugs and one extra clip. “Rose? Any chance this is the Godmother?”

“If we’re lucky,” Rose said, still staring at the basement. “She’s less likely to set the house on fire with us inside.”

Hank’s lips curled, then, some ugly parody of his usual smile. Muttered something in Spanish I couldn’t catch.

“Henry?” Mother’s breath hitched. “Sweetheart, it’s going to be okay.”

Hank laughed. There was an unfamiliar note of hysteria riding it. “I’m not the one who got shot, Evelyn.”

“I’m fine, darling. Our new friends have poor aim. Teach them properly, won’t you?”

Hank grinned at that. “Love to.” He scooted backwards through the broken glass until he could crouch beside the window. “Definitely Moll’s people,” he said, and shot one.

“How many?”

He glanced at me bleakly. “Lots.”

How the hell had they found us? My engagement to Ella was common knowledge, but Moll had no reason to suspect that Rose was stashed here. Unless—if one of her goons had tailed us, while Hank and I were busy bickering, then we’d have led them straight to Rose. Moll’s man could’ve parked far away, maybe right where Nguyen’s car was now, and crept over the grounds to the basement window. Cut the brambles away and peered inside.

And went to fetch Moll’s army while we were busy telling stories. Great.

“We need to call the police,” Mother said.

“Screw the bulls.” Rose tried to push up to her hands and knees, but couldn’t manage it. “They only help the rich. We need to help Ella.”

“Ella is rich, dear,” Mother said, and lunged for the phone. She grabbed it with her good arm and huddled under the desk as Hank provided cover fire and I crawled to the window.

There were at least a dozen men and women scattered throughout the snow. I didn’t see Moll or the Merring sisters, but half the crew wore white coats or nurse’s dresses.

“Hello, operator? I need the police immediately.”

Rose tried to push up again, failed. “It’s okay,” Jack said. “I’m on it.” And before I could stop her, she hopped from the bookshelf to the loveseat like the suicidal monkey she was.

I fired to give cover, aiming for a blonde and hitting the brunette behind her when she ducked. Jack sprinted for the basement as Hank emptied one gun into an orderly.

“Yes, this is Evelyn Prince. Send people immediately—there are dozens of armed men outside, trying to kill us.”

“Keep pressure on that arm,” I reminded as she gave the address, then dropped the phone. I hadn’t heard anything from Nguyen in a while, and he didn’t respond when I called out. I tried not to worry about it, instead aiming for the big lug kneeling behind Hank’s car. I shot the hood instead.

Hank glanced at me sourly, and shot the lug without blinking. “We get out of this? You’re getting those lessons.”

“You can shoot my heap later,” I offered, “if it’ll make you feel better.”

“Slapping you silly might make me feel better.”

“You can’t still be sore,” I said, and then pulled back before the blonde could take my head off. Hank’s second gun clicked empty, and he cursed as she fired again. I took aim—but she went down before I could take the shot.

“Sore?” Hank said, pulling his last gun. “I can’t be sore?”

“Did you see—”

“A note, Jimmy. A note.”

“I didn’t—”

“Maybe,” Rose said, “you two lovebirds can hash this out when no one’s trying to ice us.”

I winced and glanced back at Mother, who’d somehow made her way to Rose’s side. She shook her head, exasperated. “Oh, honestly. As if I didn’t know.”

Hank stared at her. “You—”

“Henry. You’ve been moping like a lovesick schoolgirl all year. Honestly, I thought I might have to intervene.”

“What happened to ugly truths?” I demanded. “Marrying a respectable dame?”

“I never said you couldn’t have lovers, dear. You’re all adults. I assumed you’d come to some sort of arrangement.”

My gun was empty, which was just as well. If Mother used the word ‘lovers’ again, I might eat a bullet. “Jack!” I yelled instead, fishing in my jacket for the extra clip. “Talk to me!”

“You done talking about sex?” Jack yelled back.

“Jack!”

Jack darted from the basement staircase to the sofa, kneeling beside Mother and Rose. There was a glint of something metal in her hand. “Ella’s not there.”

“Not—does everyone in town have an underground escape?”

“That,” Jack said, “or she went out the window.”

Hank shot three rounds and then pointed at a tree, my tree, behind Moll’s people. “There.”

I couldn’t see her through the branches and snowfall, but I caught the flashes of gunfire. “Sneaky,” I said admiringly. “That’s one button man down. Nguyen? Come on, tell me you’re alive over there!”

Nguyen appeared in the doorway. One leg was bleeding, and I couldn’t quite figure what was in his hands. “Yeah,” he said, limping away again. “Probably not for long, though. Might wanna cover your ears.”

“Jesus, Nguyen,” Hank said. “Don’t—”

But he was already outside the house, throwing whatever he had at the handful of goons taking cover behind Hank’s car. I only realized it was a makeshift bomb half a second before the thunderclap and explosion of orange flame. Hank flinched hard, and the whole house shook from the force of the blast. Nguyen was blown back into the wall. He didn’t get up.

I tried to peer through the smoke. I didn’t see any more of Moll’s men, not in one piece, anyway, but I still couldn’t spot Moll. Couldn’t tell if Ella was okay, either.

Ella . . .

Jack stood up. “I’m gonna go check on Nguyen.”

“Wait,” I said, spinning around. “Someone needs to check the back of the house, make sure no one’s circled—”

The gunshot was impossibly loud.

She fell without sound. The glint of metal, a knife, fell with her, slipping through her fingers. The Santa hat, too, floated to the carpet, red splattered against the white trim, across her temple and down her cheek.

I think I screamed, then.

There were four of them, but I barely saw the Merring sisters in their respective red and green coats, or even Moll, standing calmly a few feet behind them. I zeroed in on the gorgeous orderly with the good arms: Damian Doan, roscoe still pointed where Jack had stood.

I flew forward.

“Jimmy!”

Gunfire, in front of me, behind me. I heard all of it, none of it. I felt the slug to the shoulder, but it didn’t punch me back. I had too much forward momentum; fell straight into Damian, my gat in hand and pushing into his gut. Someone else screaming, a woman, two women. A gun clicking empty behind me. A voice—“Oh, thank God, darling,”—and Damian’s wide eyes.

“Please, don’t—”

I pulled the trigger. Then again and again, long after the bullets ran out.

I blinked hard, looked around. The Merring sisters were both down, eyes open, fixed. Hank stood just behind me, his last gun at his feet. Mother was shielding Rose and Jack with her body. Rose’s eyes were closed, and Jack—did she twitch?

“Mr. Prince.”

Moll. Bleeding from the arm, but still on her feet, iron in her hands, aimed straight at me.

“Hello again,” she said, and shot once, twice, three times.

I staggered, as hands pushed me out of the way.

Mother screamed, and Hank hit the ground hard.

I dropped beside him. Two shots had caught him in the side, the other square in the chest. His suit’s ruined, I thought nonsensically, because his lungs were ruined. Every breath he drew was a sucking wheeze that hurt to listen to.

I squeezed his hand. “Baby? Hank?”

Hank mouthed something. I couldn’t make it out.

Moll looked at Damian. She did not weep, but the lines in her face seemed somehow deeper. “Thank you,” she said, turning to me. “I may never have found Ms. Briar without you.”

Rose’s eyes were still closed. Had she been shot? I couldn’t tell. I wanted to do something, even say something clever, but Hank was dying.

Moll stepped past and I let her, because Hank was dying and the gun was aimed at Mother. “Please step aside, Mrs. Prince.”

Mother bowed her head. She squeezed Rose’s hand and stood up slowly, circling around to kneel beside Hank. His mouth was moving again, but I still couldn’t make him out. Uma. Puma. Pluma. There were tears on his face, and he was dying, and I should’ve studied Spanish harder.

Mother nodded. “It’s okay, mijo” she whispered, feeling inside his jacket pocket, drawing out a handkerchief. Drawing out a pen. It slid, hidden, into her other hand as she pressed the handkerchief firmly against his chest.

Moll did not see; she had turned mostly away from us, looking down at Rose. “I spared you once,” she said. “I can see now that was my mistake. You were always a feral thing.”

She lifted her gun, and Mother stabbed the pen through the back of Moll’s knee.

Moll cried out. She stumbled to the floor, backhanding Mother as she twisted around. She turned back to Rose —

— But Rose’s eyes were open now, and she was sitting up, fingers flexing around something that glinted.

“A free thing,” she said, and drew the blade deep across Moll’s throat.

Moll choked, falling forward and soaking the carpet in red. Her feet kicked until she went still. It took no time at all.

“Okay, then,” Rose said, and collapsed on her back.

Footsteps, from the doorway. “Jesus,” Ella said. She had Nguyen in her arms, unconscious or dead, I couldn’t tell. “Looks like I missed a hell of a—oh, Henry.”

Hank weakly touched my face with bloody fingers, mouthing something again. The color had leeched from his skin.

I grabbed his hand. “Hold on, Hank. Hold on.”

Sirens, a few minutes out. Jack groaned at the sound of them, and I laughed, or sobbed, or both. “I thought—”

“Just a graze,” Mother said, then, urgently, “Henry.”

Hank’s eyes closed.

“Hank?” I shook him, hard. “Hank, wake up. Hank, look at me; wake up. You have to; you have to give me a chance to make it right…eggs, I’ll make you eggs, just like I promised. I’m good at them, you’ll see. We’ll have a future together, you’ll see. Hank?” My voice cracked. “Hank?”

His mouth was bloody. I kissed it anyway, tried to draw him back from the big sleep, the forever sleep, the long and silent ever after.

“Come back to me,” I whispered.

And Hank opened his eyes.

We only had one instruction for the meat wagons: any hospital but St. Katherine’s.

Somehow, the Godmother was waiting for us when we arrived. I was light-headed with blood loss and a probable concussion, but I’d killed at least one person today and figured I could cut down another. Nguyen and Jack were unconscious, and Hank could only blink, but I saw Mother’s chin raise, Rose’s fists clench, and God only knew when Ella had swiped that needle.

The Godmother laughed. “Relax, chickens. I only want to talk.”

What she talked about, I couldn’t say, because the croakers whisked Hank, Nguyen, and me straight into surgery. Bullet to my shoulder wasn’t a through-and-through like Mother’s, and they spent a while digging it out. Meanwhile, Nguyen had caught a bullet himself, and there was some damage to his ears from the blast. Half his hearing gone, they thought. Maybe permanent.

He’d disappeared, by the time I woke up. The Godmother, too. But Jack was awake, by my side.

“Full bill of health,” she said, and immediately swayed in her seat.

“Mostly full bill of health. Temporary vertigo.”

“No climbing IV poles for you, then.”

She stuck her tongue out and stole my pudding.

Ella wouldn’t be climbing anything, either; it was amazing she’d made it up that tree. The shot across her back had been shallow, a graze, but she’d broken her ankle and wrist going down the stairs. I found her nursing both at Rose’s bedside.

“Prince,” Rose said, as I leaned in the doorway. She patted the mattress beside her. “Word is, I owe you a rescue.”

I smirked, stayed where I was. Lit a gasper with moderate difficulty. “All I did was find you. Zero for infinity on actually rescuing anyone.”

“Maybe you’re trying to save people who don’t need saving.”

I inclined my head. “Maybe.”

“You,” Ella said, crossing her arms, “definitely needed saving. You’re just lucky I had the good sense to ignore you.”

“Disobedience.” Rose grinned.

“Get used to it.”

“So, that’s it then?” I asked Ella. “Leaving the spotlight for a life of crime?”

Ella shook her head. “No, but I can’t leave the shadows for the spotlight, either. Everyone in Spindle City lives a double life. I’ll find my own balance.”

“Sure,” I said. “Rose is gonna need help, now that she has Moll’s empire to run.”

Ella startled, but Rose only fluttered her eyelashes. “I can’t imagine what you mean.”

I laughed. “Save it. What was it you said last year? Out with the old? Change is coming?”

Rose eyed her hospital gown. “Not exactly how I planned it shaking out.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But still seems you came out on top.” I looked at the pair of them: beautiful, and just a little bit off the track. “I can figure why you two became friends, but I still can’t figure when.”

“Before I fled Spindle,” Ella said. “The Godmother found me a place to lay dormy—”

I turned to Rose. “And you had the extra cot.”

She nodded. “I knew I’d need allies. And Ella, well. We had some similar life goals, goals I may have played up.” She winced. “I loved them, my parents. But I didn’t do it for them.”

Ella rolled her eyes. “You say that like I don’t know you.”

Rose smiled. “Anyway,” she said, after a minute. “That’s all old news. I want to hear about you two. They say there’s trouble in paradise?”

More like stagnation. Ella and I needed to talk about our little arrangement, but I didn’t know what to say. Every time I tried . . .

“How’s Hank?” Ella asked me.

I tipped back my head and exhaled.

Hank was improving, but slowly. On the upside, he hadn’t contracted the Pins, despite any reckless kissing, so I could breathe a little easier about that vaccine, not to mention throw it in the faces of those Jesus-soaked lunatics outside. On the downside, Hank spent a lot of time in pain or asleep.

A week after the shootout, I sat by his side, stretching my legs on his bedrails, while Mother read the Daily Trumpet next to me. Between her connections with the bulls and my connections with the paper, we’d managed to spin a story close enough to the truth: disreputable gumshoe sticks his nose where it doesn’t belong, a drug lord retaliates, the bulls save the day.

Mother set the newspaper aside, touched Hank’s unshaven face. He didn’t react, out cold from the morphine. “I met Henry when he was ten. Did he ever tell you how?”

I shook my head, stunned.

“Well, then, I certainly won’t. That’s his secret to share. But he was such a sharp, brittle little boy. I had to help him. I couldn’t know how much he would someday help me.”

Mother’s fingers trembled as she smoothed hair away from his forehead. Twisted something in my gut, seeing her so vulnerable. It was like I didn’t know her at all.

“Hey, it’s okay,” I said, dropping my feet to the ground. “Hank’s gonna be fine. White coats all said so.”

“Yes,” she said, looking at me. “But are you?”

I swallowed, looked away.

“How are you affording the medicine? Can you afford it?”

I had six pills left. “It’s not—it isn’t—”

“You can’t, can you?”

I didn’t say anything.

Mother nodded. “You have to let me help you,” she said, and her voice wasn’t even at all. “With this one thing in your life, Jimmy. You have to let me help you.”

“Mother, I can’t—”

“No,” she said, and then she was crying, and I didn’t know what to do. “I won’t watch my son kill himself because he’s too proud to ask for help. I don’t care how much it costs or how far the disease has progressed. I don’t care if you still blame me for Tommy—”

“I don’t, Mother, I—”

“I will not watch you die. If I have to tie you to a bed and shove pills down your throat, Jimmy. I won’t watch you die. I won’t. I—”

I hugged her. She cried into my shoulder.

“Okay,” I whispered. “Okay.”

I spent Christmas at the hospital. Carolers came to visit the patients. Hank, more awake now, kept me from shooting them.

“Maybe homicide shouldn’t be our holiday tradition, Jimmy.”

“Little too late for that.” I dropped his present on the table: a plate of eggs with a big, red bow on the side.

He laughed, delighted. “You’re such a sap.”

“Shut up and eat em.”

Hank did, grinning the entire time. “So you know,” he said. “Your Christmas present is that I’m still alive.”

“Fine. But you can’t use that next year.”

I glanced at the clock. By now, Mother was probably sitting down to dinner with Father. He’d been by the hospital only once, told me he was glad I was alive, and that he wouldn’t see me until I stopped embarrassing the family with dangerous antics.

The conversation didn’t end well, but then, it never did.

Jack had invited Ella to come by, but we were still supposed to be fighting. Instead, she stayed home, eating Christmas dinner with Rose and, surprisingly, Nguyen. Somehow, she’d coaxed him into occasionally dropping by. His full hearing hadn’t returned, and she told me the shakes were worse, but he kept coming back, so that was something.

I was glad. We still weren’t friends, but when you nearly croak with someone, you start gaining a vested interest in their wellbeing.

“Jack should be here soon,” I said. “But before that—”

“You wanna talk about the Godmother? Or Ella?”

Both would have been good ideas. Ella and I still hadn’t made any decisions, and while Rose had somehow squared things with the Godmother, I didn’t know where I stood. Hadn’t kept my promise, after all. Found, but not delivered.

But those were tomorrow’s problems. “I figured out your secret,” I told him. “Didn’t mean to, but. You know how I am with a puzzle.”

Hank looked intrigued. “I have secrets?”

“Old ones,” I said. “About twenty years old now.”

I hated how the smile slipped from his face. “Suppose it was losing my head at Ella’s that gave me away.”

It was that. It was a few things. Knowing Hank and I were the same age, and that ten was a very bad year.

“My father got sick first,” Hank said. “Then my mother, my brothers. They threw us all in the burning shack. Already lit the fuse when Evelyn found us. But she got us out. She saved us.”

She couldn’t have saved his family. The pills wouldn’t come for years, but they didn’t have to die in smoke and flame. That meant something, anyway.

“Evelyn smuggled me out of Spindle City,” Hank said. “Set me up with some good people. I came back, years later, when I was grown. I wanted to help.” He smiled softly. “Nicer suits, too.”

I laughed. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Because, Jimmy. She hadn’t come looking for me.”

Right. Right. She’d gone looking for Tommy, and found Hank instead. “You think I’d blame you for that?”

“No,” Hank said, after a minute. “I don’t suppose you’ve forgiven yourself yet, though.”

I didn’t say anything.

Hank’s eyes were kind. “That’s okay,” he said. “One Christmas miracle at a time.”

When Jack walked in, she was humming “White Christmas” and wearing her Santa hat, the one with bloodstains on it. I knocked it off and replaced it with my fedora.

“You forgot to get me an actual present, didn’t you?” Jack grumbled from somewhere underneath the brim.

I tipped it back so she could see the business card I slid into her hand: Prince & Jack, Detective Agency.

Jack’s eyes got big.

“Listen,” I said. “The, uh. Legwork. I won’t always be able to do it. Nothing’s gonna stop me chasing puzzles, but, well. You’re better at climbing trees than I am anyway, and let’s face it: you’ve been more gumshoe than secretary for years. Figured it was time to make it official, if you’re in.”

Jack bit her lip, looked away. I pretended not to notice her wet eyes. “How’s it look?” she asked Hank.

He smiled. “It suits you.”

“Yeah,” Jack said, grinning. “Yeah, I thought it might.” Then she hugged me, full-force, the hat sliding halfway off. “Merry Christmas, Jimmy.”

I kissed the top of her head. “Merry Christmas, kid.”

THE END

Buy the Ebook

Amazon US | Amazon UK | B&N | Kobo | Smashwords | Google Play

Buy Direct from The Book Smugglers

DRM-free EPUB or MOBI

Add the book on Goodreads.

10 Comments

Fangirl Happy Hour, Episode #30 – “Don’t Cockblock Your Parents” | Fangirl Happy Hour

December 23, 2015 at 2:18 am[…] References Intro; 00:55 Flutter by Momoko Tenzen Skip Beat by Yoshiki Nakamura “The Long and Silent Ever After” (Spindle City #3) by Carlie St. George Let’s Get Literate! Black Hole November […]

Where Are We Now?: Carlie St. George | Notes from the Teleidoplex

July 8, 2016 at 12:25 pm[…] how could I ever choose between them?—but I’m probably the most proud of my Spindle City trilogy at The Book Smugglers. A lot, a LOT, of work went into those stories, and there was a time I […]

Anonymous

March 11, 2017 at 7:57 amI love these stories! Bought all three.