Welcome to Smugglivus 2014! Throughout this month, we will have daily guests – authors and bloggers alike – looking back at their favorite reads of 2014, looking forward to events and upcoming books in 2015, and more.

Who: Octavia Cade has very nearly finished her PhD in science communication at the University of Otago in New Zealand. Her short fiction has appeared in Strange Horizons, Cosmos Magazine and Aurealis, amongst other places. Her most recent novella, Vita Urbis, is also stuffed full of retellings. Octavia has also written not only one of Ana’s favourite stories of the year – Trading Rosemary – but also The Mussel Eater, one of the short stories we published this year (which you can read here for free).

Give a warm welcome to Octavia, folks!

Far and away the best novel I’ve read this year is The Swan Book by the Australian Aboriginal author Alexis Wright. When I say “far away”, I’m talking an order of magnitude, here. Partly because the book is just that good, but partly because it ticks off everything I like best in a science fiction book: something that straddles the line between literary and genre, something about people, something with a setting that’s recognisable. Don’t get me wrong, I’ll read space opera, for instance, as willingly as the next girl – but I want most the stories set on this world, the ones that are the-same-but-darkly. And, above all else, the stories that are written for love of language.

You can always tell them. They’re the ones with prose you can drown in, thick and sticky and sweet as cream. Mervyn Peake wrote prose like this – and Angela Carter, and Salman Rushdie, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

I’ll forgive a lot for language. It’s such a sensuous thing – the shapes the syllables have in your mouth, the way that sounds link together. Words have taste and smell, they hang in little grape bunches. Get it right and I’ll forgive any idiot plot, any flat character. Language is the little brass key that unlocks the hard dark planes of my heart.

There are three speculative fiction books that have come for me in the shape of keys this year. The first is, as I said, The Swan Book.

Set in future Australia, where climate change has made refugees of half the world, a little Aboriginal girl is found abandoned in a community that has also been abandoned, segregated, locked away. Oblivia is mute, traumatised by a gang-rape that is barely alluded to and yet in clear concert with the exploitation all around – the land thefts, the stolen generations. She is raised in a rusting, deserted ship hull in a swampy marsh by an old woman who is a refugee from a northern country overrun and made uninhabitable by shifting climate, and that woman has brought her stories to Australia, the stories of swans that begin to appear in the marsh, that form a bond with Oblivia. The swans follow her south as she is taken from her home, taken south to a tower and marriage and the assumption of her role as first lady of Australia – a role that Oblivia never wants, in a tower circled by swans and routinely cut off by tides. It’s a terrifying future, a commentary on race relations, on relationships with the land, of belonging and exploitation and ghosts that never leave – but the real strength of The Swan Book is the language. The ambiguity, the dreaming. It is unrelentingly gorgeous, spellbinding and soporific. I can’t recommend it enough.

Runner-up position goes to Gretel and the Dark by Eliza Granville. A dark, fractured fairy tale of life in WW2, it alternates chapters between a spoiled little girl who ends up in a concentration camp, and an elderly doctor who finds a mysterious young woman who claims she is a machine. These two stories connect towards the end of the novel, although one can sort of sense how they’re going to intersect. The risky thing about the structure here is how easy it is to prefer one storyline over the other. For me, the little girl Krysta has the far more interesting story, so I would always feel a bit disappointed when it came time to go back to Josef. That said, the language is so beautiful, so darkly fantastic, that it covers a multitude of sins and I say that deliberately, not wanting to spoil. Granville’s language is so different from Wright’s – there’s an enormous cultural schism between them, after all – but in both cases it’s the strength of the respective books, and really almost hypnotic.

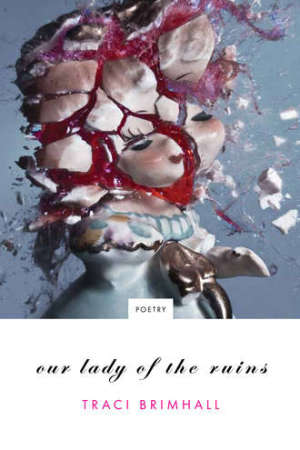

Second runner up is perhaps a trifle unfair, as it was published back in 2012. I read it then, superficially I expect – referred to it in my thesis, even – but the better kind of book is more than ephemera, and bears rereading. No, demands it. Traci Brimhall’s poetry collection Our Lady of the Ruins has spent most of the past year on my bedside table. I keep going back to it, and if 2012 was the year I first read it, 2014 might be the year I really began to understand it, to feel its imprint on my bones. Set in a post-apocalyptic world, it traces the wanderings of a group of women – their experience of pilgrimage and exile, wrapped up in the language and images and metaphors of myth. It’s really astoundingly good, and as poets are so constrained by brevity their focus on vivid, striking language is that much more important.

So, these are the three books that have stuck with me this year. There’s really none that I’m actively looking forward to next year. I don’t say that to be dismissive. I’m certain there’ll be some fantastic ones, but it’s my experience that books – the right books – turn up when you need them to so I try not to look ahead.

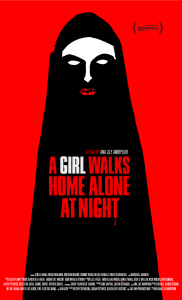

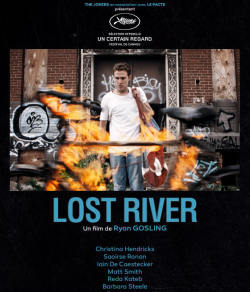

Strangely, that’s not a feeling that adheres to cinema – I’m on tenterhooks for the Iranian vampire horror film A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, the science documentary Particle Fever and the fantasy Lost River. (Again, I’m aware that some of these have already been released, but I live in New Zealand. It can take a while to get here.)

I look forward to movies in a way that I don’t for books. I suppose it’s a product of different expectations. I look forward to ice-cream, or to birthdays. I don’t look forward to breathing. Books are breath. They’re with you always.

No Comments