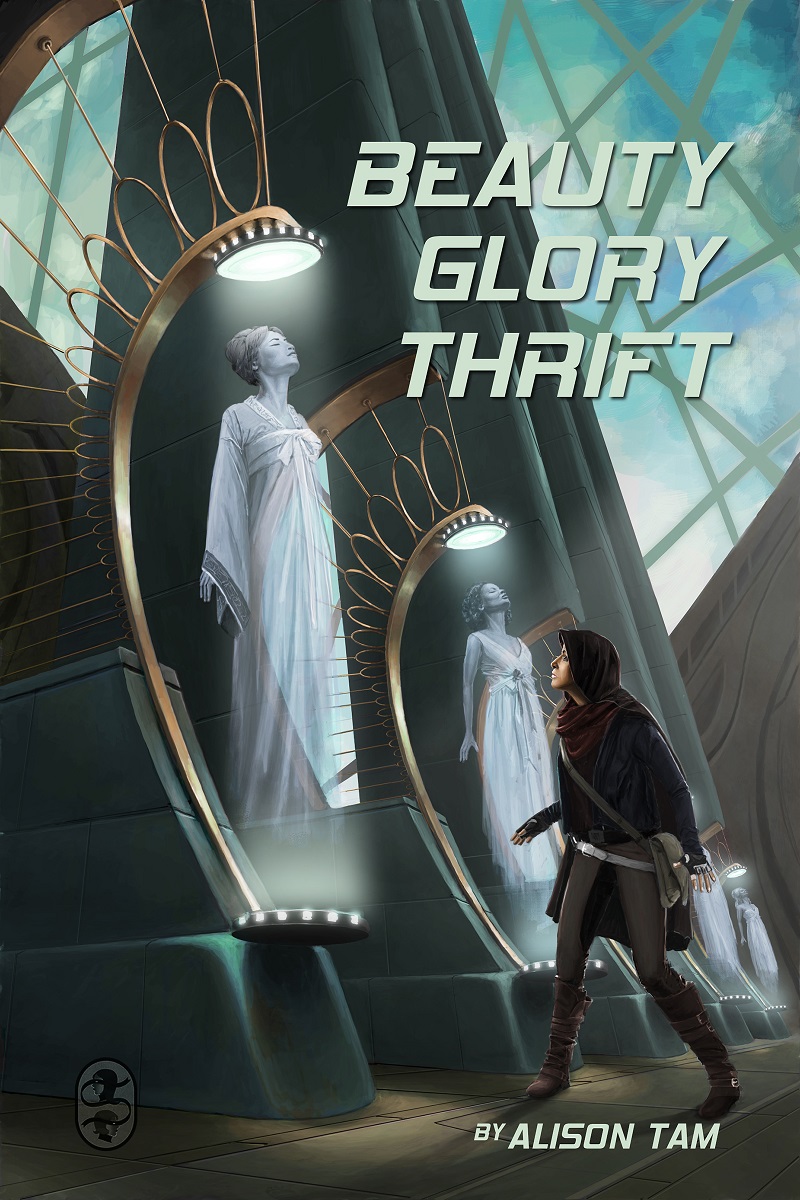

Beauty, Glory, Thrift by Alison Tam

Published 6/13/2017

I am Thrift and I want to leave this place, and see the far ends of the universe, and never spend another moment in stasis ever again. Take my hand and bring me with you…

On a lost planet in the depths of space, goddess-sisters Beauty, Glory and Thrift split their time between stasis and bickering, forever waiting for new visitors to their forgotten temple. Enter a thief, who comes searching for treasure but instead finds Thrift—the least of the goddesses—who offers powers of frugality in exchange for her escape.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

![]()

The lights, when they came on, woke my sister Glory first. We had been drowsing in that deep, dark familiar haze for I know not how long, but then she gave a cry, and we all awoke in turn.

“Someone’s here,” she said, and the news spread among us with a murmur of anticipation. Confined to our altars as we were, our only entertainment the silly games we played amongst ourselves and the enticing lull of sleep, any visitor sent us into a flurry of speculation. It could be a princess, suggested my sister Beauty. Wisdom wanted an ancient scholar, and Innocence was holding out for a dog.

“It could be a hero,” I said, “Clad in golden mail, with shining silver pauldrons and a plasma rifle encrusted with jewels, her spaceship slipping silver-bright through the stars. Couldn’t it, Glory?”

“Nonsense,” she said, dismissing me without even a glance at my direction, so focused was she on trying to peer past the doorway. “She’s just a thief. I see her putting the good incense pot into her satchel.”

If anything, our excitement rose. A thief! Romantic, dangerous, daring! Beauty threw back her hair and flexed her biceps. Artifice smoothed out her scarf, winding the long strands at the end into an elaborate knot. Even Glory stood a little taller, though she held herself above any of our obvious signs of preparation. When the thief finally walked in, her hands in her pockets and her gun worn low on her hip, all of us shone.

“Come, traveler,” said Glory, as the thief stepped across the doorway, “And I shall give you a boon. Take me with you and your bullets will never miss their marks. You will never have cause to fear battle again, and the entire galaxy shall exult in the sound of your name.”

“I’m good,” said the thief, and walked onwards. Beauty, shooting a triumphant look at Glory, stepped forward as the thief neared her altar.

“Stranger, stranger,” she called. “Come, and you will receive a gift beyond measure. Take me with you, and you will never feel anything but perfect. You could have any lover you wish in the universe, and everyone you see shall meet your gaze with delight.”

“No, thanks,” said the thief, and walked onwards. She denied Wit, and Mercy, and Toil besides. Wisdom didn’t even try. The thief passed through the whole hallway without ever sparing me a glance; by then, of course, she was sick of my sisters’ entreaties. I watched her walk by, the swing of her hair, the heavy thump of her boots on the floor, thinking that I would go the way of Wisdom. But as she left, I was struck with the thought of another hundred years of pointless existence, alternating between nonsensical chatter with my sisters and sleep, every bit of conversation worth having already said.

“Wait!” I yelled, and, miraculously, the thief halted.

“I am Thrift,” I told her. “I am Thrift and I want to leave this place, and see the far ends of the universe, and never spend another moment in stasis ever again. Take my hand and bring me with you. Please.”

“What’re you going to give me, then?”

I hadn’t the powers of my sisters: I could not make a bullet fly true, or curl a lock of hair just right, or fry an egg to perfection every time. If I had blood in my body, my face would have flushed at the thief’s question. I had always been the least of my sisters, lacking the confidence of Beauty, the quickness of Wit, and wholly without any of the grace, strength, or power that Glory claimed as her own. I grabbed at my altar, more for comfort than balance, and in so doing, my hands closed around the only offering I had to my name.

Had the offering been anything else, I would not have made so bad a bargain. My whole being still burns with shame to think of it. But in a time of desperation, any deal was a good one, even if I was giving away the only possessions I had in the whole world.

“Fifty creds!” I said, triumphantly, holding up two coins in my palm, and watched in dismay as the thief shook with laughter.

“This is more than you think it is, thief. And I’ll prove it to you, if you give me the chance. Take my hand, and I will turn these fifty creds into a feast.”

She laughed still louder, the sound bouncing off the narrow walls and low ceiling, my sisters leaning in, ready to mock me once I was denied. The thief wiped a tear from her eye. I was standing there in stupid silence, hoping beyond hope that either I or my sisters would perish in the next few moments, when she, still laughing, reached out and took my hand.

I emerged from the cold, cramped, dark of the temple as if from the womb. Suddenly there was light once more, and the sudden pressure of the thief’s hand on mine when before I only knew sight and sound. I could feel the impact each time the thief took a step, foot against floor. Her clothes shifted on her body as she walked, and I could feel that, too, the rasp of cloth against flesh. And then there was smell, of stale air and metal and the headiness of incense, the one sense I barely even remembered.

“What’s that you’re doing, with your ribs and your nose and the thing moving inside your body?” I asked. The thief gave me a strange look, letting go of my hand.

“I’m not doing anything.”

“You’re doing it right now, it’s—” I moved my hand, mimicking a rise and fall.

“You mean breathing?”

Breathing. I had forgotten about that.

“I promised to show you my skills,” I said, changing the subject. “Follow me.”

I did not know how long I had been asleep, insulated from contact with the world outside, as ignorant as a chick in a shell, but it only took a touch to the Oracle’s network to tell me how things were now. That, even more than the sensations of the physical, was at once new and familiar, something that I knew intimately and yet did not remember. Information rushed over me like water through a mill, every single point of data another drop.

We steered towards the shipyards, where unofficial vendors had set up their stalls. I couldn’t speak to them directly, kept non-corporeal, only able to manifest through the thief’s consciousness, but she let me guide her through our purchases with good grace.

It would be a simple meal. Ten creds for water, ten for rice, five and five again for the most unattractive vegetables and fish bones cleaned of everything but the head and the tail. Ten creds went to an engine core diffuser, and the last ten were spent on chopsticks and two bowls.

The diffuser was made of three parts, stacked atop each other. In the first, I poured the water and placed the fish bones. In the second went the rice and what little water we had left. The third was where I put the vegetables, which would cook in the rice’s steam.

“And now we need only heat,” I said, already thinking of how to sneak into the station’s thermal generators when the thief began walking in the opposite direction. Try as I might, I couldn’t help but be pulled along.

“I have a place,” she said, and led me to—just as I had imagined!—a ship, elegant in its sloping lines, silver shining where the light hit the scuffs in its dark blue paint. Inside it was silver, too, and hearth-warm, three shining screens flickering to life the moment we walked in. I gaped, then looked at the thief to be sure that she had not caught me gaping. She connected the engine diffuser to a port in the wall.

“See? Heat.”

I kept asking her questions about the ship (where it had been made, and where she had got it, and did she know how it worked), to which the thief hadn’t any sort of satisfactory answers. Eventually she deigned to tell me about the largest ship she had ever seen—Generation-class, meant to bridge the gap between galaxies, and that story lasted us until our meal was done.

“Not bad,” was the thief’s verdict. I did not reply. The heat of the broth against her tongue, the taste of fish, the texture of the rice against her teeth—I could not speak, and barely managed to hear her next words.

“But if it’s all the same to you, I don’t think I need your services for any longer,” she said, barely even sparing me a glance, “End program.”

She’d left the diffuser on the floor. What a waste! I could not pick it up, and as she walked away I was pulled uncontrollably with her. She didn’t notice me for a good few seconds, and started with a little jump when she realized I was still drifting along beside her.

“I said, end program. Computer, delete—what are you again?”

“I am Thrift,” I said, “Though my sisters call me Chechine, which means ‘smallest one’, and—”

“Computer, delete Chechine. Delete Thrift. End Chechine.”

The timbre of her voice lowered with each word, and I could feel the strain in her voicebox as she ended her last sentence with a hiss.

“Are you fucking kidding me? Thrift, Chechine, whatever, how the hell am I supposed to make you go away?”

“Away?” I echoed, witless as ever. Had I not shown her how useful I could be? Had I not proved my worth?

“Away. Back to the… wherever you were. Terminate user license.”

“Our bargain—”

“It’s done, isn’t it? You showed me. And now I’d like you to go back. How do I make that happen?”

I couldn’t go back. That room, in the darkness and the quiet, no smelling or hearing or touching, had been like death in its absence. I couldn’t go back there, now that I had felt again, and tasted. Even emotion was only real as long as I was attached to the thief: I was facing the despair of return, yes, but that paled in comparison to the physicality of her anger. Her muscles tensed, her shoulders squared, her lips pulled back in a snarl…

Besides, I did not know how to go back, and I told her as such. I didn’t think (despite even Glory’s greatest efforts) we’d ever had anyone leave.

She stared at me with disbelief. Had she been able to hit me, in that moment, I think she would have, but she didn’t waste her time on a blow that would never connect.

“All right. Whatever. If you can’t do it, I’ll just go see a doctor.”

The thief’s doctor was off-Station (off-Station!) and though I was rather occupied with the dizziness of space, of having escaped not only my altar but my whole world in one fell swoop, I still had enough presence of mind to make some ingratiating conversation. Perhaps if she liked me enough, I could stay, and to that purpose I tried to talk to her about her name (she wouldn’t tell me), her profession (she didn’t respond to any of my flattery, though I even went so far as to name her the best of all burglars), the stars (beautiful), her appearance (more beautiful, I insisted) and any other small thing I could think of, all of which she soon began to ignore.

We docked at another station, though it was large enough as we neared it that I thought we had come across a planet in its own right. If I had attention enough to speak earlier, I’d lost it. There were so many people at this station, so many different species, clad in all sorts of strange garb, chattering as they cooked their peculiar foods. Since none could see me, it would not be rude to stare. I swiveled to examine an octopus’s dinner, which did rather look like ours had, with eels instead of rice, then to gawk at the brightly-flashing holographic signs by a storefront (COFFEE AND TATTOOS), then turned again at the sound of an eagle’s shriek.

“Is it really that interesting to you?” asked the thief, pulling me away from inspecting at the delicate feathers on the eagle’s nape as she navigated the crowd.

“Isn’t it interesting to you?”

She shrugged, deftly squeezing through the gap between a pink-robed priest and a woman with a whole jungle’s worth of vines twining through her hair.

“I’ve seen better. The crystal towers of Luoxia. The markets of Marrakite. Waterfalls on Undine IV.”

“What’s a waterfall?”

She couldn’t keep herself from an incredulous glance at me, though she had avoided looking ever since we left Station, unwilling to acknowledge, perhaps, a vision of a woman only she could see.

“What’s a—Jeez. Maybe you’ll get to see one someday.”

“You could take me,” I suggested, with my most charming yet pitiful smile.

“Not likely.”

Eventually she led me towards one of the less-neon hallways, through a kind of back alley, ending up at a dingy room with a paper sign that read PRACTICAL MEDICINE. It did not seem like an especially sterile environment, unidentified stains in every corner, and I shrank closer to the thief, hiding from the many-headed woman sitting at the front desk, each one of her heads bent towards a different stack of papers.

“Doc?”

One head emerged, squinting at the thief.

“Here again, Pak?” said the head (all the others were still focused on their reading, though on one of them I could have sworn the lips moved), “What the hell did you fuck this time?”

“I didn’t fuck anything,” protested the thief (Pak, I suppose, though the name felt awkward in my thoughts), “I… found some software. On my last run.”

“And, let me guess, you decided to put it in your brain.”

“Hey, I just need you to tell me how to uninstall it, okay? I thought it was safe. I mean, hell, it’s just accounting software, shouldn’t be that hard, right? Search for it, she says people call her Chechine.”

I gasped in indignation and floated in front of the thief so she’d have to look me in the face.

“Accounting software? You think I’m accounting software?”

“What else would you be?” asked the thief, and, to the doctor, “Sorry, not you, the, uh. The software’s talking to me.”

“I am the goddess of Thrift, radiant and undying, the blasphemer’s bane. I’m—I’m—”

Glory could have said more. I was incoherent with anger, never the most eloquent of my sisters even at the best of times, and, besides, I had always been a little hazy on the details of my existence.

“She says she’s a goddess,” said the thief, and the doctor, sighing, brought another one of her heads up.

“I’ll take a look.”

Her eyes glowed (all of them, not just the ones scrutinizing the thief) as she scanned, and I twisted to see, not sure if I could distract her and not sure if I should. In the end, she blinked, once, twice, and clapped the thief on the shoulder.

“No idea.”

“You kidding me?”

“I’ve never seen anything like this before. It’s your own fault, anyway, for downloading alien malware onto yourself. What were you thinking?”

“What was I thinking, coming to you for help,” grumbled the thief, and glared at me. I did my best to keep the triumph off my face, but sometimes even I cannot help myself.

“Maybe you just like seeing my faces,” said the doctor, and then, taking pity on the thief, “Look, your best bet is finding the manufacturer. I can’t help you here.”

The thief returned to her ship (what I had begun, presumptuously, thinking of as our ship), stripping off her jacket and throwing it into a corner, then picking it up and throwing it against the wall for good measure.

She stared at that wall for a good long while. Wisely, I decided not to speak, hovering around the edges of her awareness but never quite daring to enter her line of sight.

I could feel everything she felt, after all, every last bit of an emotion that I could not decipher. I drummed my fingers to the staccato beat of her heart. I counted the seconds between each raggedy inhale and exhale. I clenched my fists and pretended that the blood coursing through her veins was my own.

Eventually, she turned towards me.

“I don’t suppose you’d know where you came from?” she asked, an ironic twist to her mouth. I shook my head. She snorted and once again turned her head away, this time to the ceiling.

“Great. I just had to download the defective one.”

“I’m not—”

I don’t know how, but she pinned me with a glance. I quieted, voice subsiding. She sighed, sighed again and stood, picking up the satchel full of pilfered items from my temple.

“Well. We better sell these off first.”

I kept my face impassive, no small feat when I had but two days’ practice controlling my features. We, she had said. We.

Determined to be useful, I bent all my talents towards helping the thief hawk her ill-gotten gains. I am the goddess of Thrift, after all, and if nothing else I knew how to drive a bargain. We visited the various scrappy outposts of the forgotten outer edges of civilization, where looking at your fence the wrong way was liable to get you shot. Every time we stepped foot on those bases, the thief’s heart rate shot up in an adrenaline response.

I was bound to the thief, only seeing what she saw and hearing what she heard, but still I spent every moment we were on-station dazed with overstimulation. So many signs to stare at, and people to bump into! Twice I pointed out a pickpocket inching too close to the thief’s loot, and every time we entered a negotiation my focus would reluctantly narrow to the transaction, blocking out all the interesting sights and smells around us to whisper in the thief’s ear:

“Get two of the smaller cans instead of one large one: you’ll have more fuel that way.”

“She’s got a picture behind her desk. Ask her if she’d like to buy the necklace for her wife.”

“She’s willing to go lower. I can feel it. Pretend like you’re giving up on the deal.”

When a deal went well, the thief would let me choose our last meal of the day, a show of generosity or of thanks. This is how I discovered tree-worms, which wriggled for escape even halfway down her throat, and the large fibrous leaves served at one particular station that tasted sour and had no name, and sugar-flies, spun from sucrose, delicate enough to melt the minute they touched her tongue.

“I used to have these, when I was a child,” I said, bidding her to lick the melted imprint of sugar off her palm. “Or something like, at least. The ones I had tasted like fruit.”

“Are goddesses ever children?” she asked, her gaze sidelong, considering. I paused, stuttering, the phantom imprint of her tongue still moving over her hand.

“I must have been if I remember it.”

She made a low noise at the back of her throat, a final hum, and gave her hand one final lick. I tasted sugar, and salt.

Just like that, we settled into a routine: ambling through crowded stations, conversing idly as she brought her ship into port. We saw space stations, asteroid mining belts, gardens and amusement parks built onto the far sides of moons. The first time she brought me onto a planet, I could have wept. Everything was so large outside, the gravity weighing heavy on her spine. Even the quality of air was different, a new and interesting smell presenting itself with every inhale. Each day, we would go off to the markets—selling this thing, stealing that-and each night, backlit by the faint orange of her computer monitor, she would search for the place I should have called home.

The thief took… I didn’t quite dare call it joy, but she took a certain satisfaction in telling me the tips of her trade, and could be sent on a storytelling tangent with almost ludicrous ease. She established an uplink to the ship’s computer while she slept so I could access any media files I wished.

“It creeps me out, thinking that you’re just floating there all night, feeling me sleep.”

“I do not,” I said (even though I did) and she laughed like she didn’t believe me. I liked her laughter, the way it rumbled up through her throat, the lightness in her chest.

We went to the androids’ opera, supposedly to steal pocketwatches and cufflinks, but she let us sit through the whole performance, as twenty-seven metal prima donnas sang in alternating harmony. We spent an hour in a planet’s atmosphere, doing barrel rolls. We went to see a waterfall, finally, and I had her place her whole body beneath the falling water just so I could feel it pounding against her frame.

There was a vendor at the edge selling suits that would let us ride over the edge of the waterfall and yet survive: something to do with large amounts of padding, air bubbles and peculiar design. Each was printed with the logo of a different company, bright-colored nonsense and mascots with bulbous eyes and thin membranous wings.

“Let’s go do that,” I said, wishing that I was my sister Beauty, who would have taken a hold of her wrist and pulled her along, or placed a guiding hand along the curve of her spine. Even intangible, Beauty would have found a way. Instead I floated, an awkward ghost tethered to the thief’s vision.

“You’re getting greedy,” she told me, but bought one anyway, and we sailed into the vast mass of churning water as one.

Slowly, I began to forget about ingratiating myself to her, stopped trying to anticipate what the thief would want me to do or say. We argued sometimes, became sick of seeing each other’s face other times. But always after those first few resentful hours, I would drift back into her line of sight, or she would ask me what I wanted for lunch.

I only wished I could avoid her when she had to communicate with the ship, a long process that involved plugging a cable into her neural implants. I could feel the information and commands passed between the thief’s mind and the slow, ponderous automation of the ship’s systems. There was something disquieting about those signals. They felt so much like my sisters’ conversations, but without the wit, the pettiness, the play, as if someone had taken Glory or Beauty and drained them of everything that made them themselves. Intelligence without personality, calculation without interest or meaning.

Was that what the thief thought I was? Was that what I felt like to her? Sometimes, in my most nervous hours, as the thief slept, I wondered about her hypothesis that I was only software. Perhaps I was not much different from our ship’s meticulous, automatic processes of action and reaction, query and response. On those nights, as the thief dreamed with her connection to our ship still live, I drifted in a sympathetic state of half-consciousness, not sure whether any idle thought had come over the wire or was one of my own.

“You should take me dancing,” I suggested one night as she flicked through the ship’s logs.

“Take yourself dancing,” she grumbled, and I laughed in protest. My laugh was but a pale imitation, mimicking her motions in mirth without being able to feel her chest convulse with joy, but I found that if we laughed at the same time, and I matched my every movement to hers, it was almost the same.

But this time my thief wasn’t laughing. Drifting further into her line of sight, I froze at the expression on her face. Perhaps I could’ve borne it better if she kept her expression blank or even menacing, as she had in the early days of our acquaintance, but there was nothing in her gaze but a soft pity I trembled to see.

“We don’t have the time today,” she said. “I found your home.”

I didn’t speak to her the whole way there. Not in the way Beauty had of being silent; with one haughty lift of her chin, you knew you had disappointed her terribly and could never again regain her good opinion. Mine was a small, sad, shaken quietness, of subdued posture and reflexive smiles. The thief, to her credit, did not try to make me speak. She pretended to fiddle with the ship’s navigation, head bowed, as I huddled just out of sight, transfixed all of the possible ways I had gone wrong.

The journey, she let the ship tell me, would only take a little more than a day—nothing compared to the weeks we usually took to traverse the emptiness of space. Hearing that sent me further down the spiral of spite and self-recrimination. Had she been planning this? Had she plotted us out a course that would take us ever-closer to separation, never telling me, never even considering that I should be told? I wondered how long she’d known, if it had been weeks or months, or even longer, of my blithe ignorance, if all this time—

I made my hands tighten into fists, but even this reminded me of my own insignificance. It was a purely visual gesture, nothing without the strain of the muscles in the thief’s forearms, the half-moons of her nails digging into her hands. Glory would have said that the gesture was unbefitting of a goddess, petty and resentful, as if we were not all those things and less. She would have said something about the dignity of our station, as if siphoning my only sensations off the thief did not make me feel like a lesser shade, as if my being a goddess had ever been of any use. Glory was one thing, and Beauty another, as were Wisdom and Wit and Mercy—but they all thought of me as the smallest one, the lesser to all of their greater gifts, as if I did not even deserve a name.

Surprised that I could think so bitterly and feeling terribly sorry for myself, I stayed out of the thief’s sight and floated by the window for longer than I would like to admit. My mind filled with impossible scenarios: a sudden arrest, a change of heart, an engine failure that I alone could fix. Only curiosity when we finally made port could pull me out of my thoughts and back to the thief’s side.

We had come up to the planet—my planet, I supposed—and the ship’s external cameras rendered it faithfully on screen, overlaid with orbiting stations like shining jewels, circled by a single moon.

“It’s pretty,” said the thief. I felt her chest flutter, and did not know what it meant. Silent, I was vaguely satisfied that the sight of that small reddish globe had not given me any sudden swell of sentiment for the Motherland to my diaspora, the primordial center from whence I came.

On the ship, I’d had more than enough time to conjure up fantastical imaginings of my home planet—my sisters waiting to greet me with open arms, a statue of myself tall enough to blot out the sun—but I had never allowed myself to linger on those ideas, shying away before I could summon up the exact details of Beauty’s face, or the color of my planet’s sky. Stepping onto the surface, I could feel the thief’s emotions better than my own, a cold, curious stillness to her body belied by the quickness of her pulse. She watched me, steadily, as I looked around. And though I was no stranger to her eyes on me (she had a habit of glancing over to catch my reaction, of drinking my wonder in), I had never before felt observed with such intent.

I didn’t know how she wanted me to react. Recognition? Joy? Grief? Whatever it was, I decided to rob her of it, and kept myself impassive as we walked through what she had decided was my home. My fantasies of planetary devotion were disappointingly unfounded, and there were no golden statues in sight. I had not expected my planet to be so ordinary, the same sort of tall buildings and neon-lit shops we had seen in countless other cities since, nor so secular.

Everything we saw, I divided into familiar and unfamiliar. Familiar was a woman we passed, who looked so much like Glory that I almost called out my sister’s name. Familiar was the cadence in a street vendor’s voice as she called out the prices of the day, and immigrants from planets we had already visited, cooking up food that the thief had eaten on our travels. Some blurred from familiar to unfamiliar to familiar again: a many-headed woman (familiar, like the doctor the thief had brought me to the first day we met) climbing into a cart that moved along a set of silver rails (unfamiliar) who raised a hand, like Beauty would, to wave at a distant admirer.

“Where are we going?” I asked, finally. We had boarded a gondola-train, almost half as high as the skyscrapers around us, and the thief had given no indication as to how long we would travel.

“So now you stop sulking,” she said, but, perhaps because my expression threatened another long, furious silence, relented and answered, “We’re headed to a library.”

She’d undersold our destination. The library she brought us to was one of the largest buildings on the planet yet, built of red metal that shone bright in the afternoon sun, flanked by golden statues of curious beasts. It was cool when we stepped in, lit by high windows, a fountain spanning the length of the entire room.

“What are you looking for?” I asked.

“You’ll see.”

I had ignored the thief’s long nights of research when we were both on the ship, preferring to watch period dramas or flip through comics as she slowly pored through whatever text she was reading, and now that I had no choice but to witness the search process, I wished heartily that I was back on the ship with Passion’s Demise on the viewscreen. The library was digital, as fragile paper books were reserved for legitimate academics, so I had not even tactile sensation to mollify me as she browsed.

Her first search: religion. I couldn’t help but perk up. Most likely I was only a footnote beside my sisters, but perhaps there’d be an unflattering sentence about Beauty’s long-windedness, or some old forgotten scandal that I could read in delight. Yet as the thief scrolled and scrolled, she found only entries about chicken-headed somebodies and ladies with snake-tails for legs. Not Beauty. Not Glory. Not any of us at all.

“So slow!” I said, at first, thinking that she was looking through the wrong database.

“I’m beginning to doubt your ability to read,” I said, next, but as the minutes passed without a sign of any of my sisters, I quieted and drew closer, my head beside the thief’s shoulder. When I spoke next, it was without mirth.

“Look for the station where you found me.”

“Always so helpful,” she said sarcastically, but she followed my advice. Soon we were reading such things as demographic information and patterns of settlement, which neither of us understood.

“Computer,” she said, “Bring up clothing trends for the past twenty years on the outer stations of the Tsishe region. We’re going to scroll through these damn pictures until I find someone wearing the same awful clothes as you are.” I looked down at my body. What was wrong with my clothes?

Slowly we pored through pictures and pictures of women in different fashions, going back further in time. One had a blouse collar, that, like mine, dipped lower at the front, but her pants flared out in a way that seemed to me perfectly silly. Another had a skirt about the same length as mine, though it ended in an incongruous froth of spikes and lace. Finally we came upon a woman draped in a robe almost exactly like Beauty’s, and though none of the other models from her era precisely matched my own gown, the thief decided it was good enough.

“Computer, bring up search results for information about this decade,” she said, and I raised a hand to stay her.

“We’re wasting time,” I said, “Ask her this: Computer, how should we find information about this decade?”

I felt a muscle in her jaw set, but she repeated my question, anyway, and the computer replied:

“For detailed historical queries, please consult the angels.”

“There,” I said. “We will go to the angels, and ask for succor, and then—and then let us be done with it, however this story ends.”

We overpaid for our ticket.

I could see it in the technicians’ eyes as they charged us: tourists and foreigners, we could be relied upon to pay a little extra. I didn’t argue, though I thought about pointing it out to the thief: see what you’ll be missing when I’m gone. They laid her body down on a reclining chair, lowered a contraption of wire and steel onto her head, and, as low, soothing music filled the room, she closed her eyes.

She opened them, and we were underwater. Only smooth glass, blown in an arc above our heads, protected us from the elements, distant sunlight, refracted through the water and the glass, dim and dappled at our feet. The thief’s senses were muted, the edges of her eyesight escaping into a blur. Even when she walked, I could register far less the impact of her foot on the floor.

Against the furthest wall sat a woman in a sumptuous gown of blue, its train so long it almost seemed as much a part of the carpet as part of her garb.

“Angel,” I said, and she turned to us with a smile.

“Hi, I’m Shenny, your guide to the Upper City today. How can I help you?”

She glanced at the thief, quick and professional, sizing her up like the thief would when calculating the price of someone’s wrist-watch.

“Are you here for a historical re-enactment? Tour? Or, let me guess—” and she looked right towards me, leaned forward, held my eye—“visiting an ancestor?”

I felt a sudden dizziness, a lightness everywhere from forehead to ribs. It was only when I stumbled forward, catching myself with a hand on the thief’s shoulder, that I realized I was not feeling the thief’s emotion, but my own.

The angel saw me. She knew me.

I registered touch, muted but direct, the indent of flesh beneath my fingers when my hand on the thief’s shoulder tightened in its grasp. She turned toward me, and I felt at once both her shock and my own. It was my hand on her shoulder, my breath escaping in heavy bursts from my lungs.

She raised her hand up towards me. I grasped it in my own, let her steady me, leaned heavily against her side.

“Wait a second,” said the angel. Suddenly she was next to us, her dress pooling around our feet. She took my face between both hands. And I, still reeling, could only cling desperately on to the thief’s hand.

“You’re one of us, aren’t you?” she said, tilting my head upward. “You poor dear. Nobody ever uploaded you.”

“We were going to ask a religious question,” the thief said. I barely heard. In that moment, I, like my planet, had been divided into familiar and unfamiliar. Familiar was: You are a goddess. You have power beyond mortal knowledge, beyond even your own. And you are small and silly and ignorant sometimes, but you are a goddess still. Unfamiliar was: You are wrong.

“I hope you weren’t going to ask about the light and the tunnel,” the angel said, “We get quite enough of that from the Lower City. And—oh, you poor dear, what am I saying? You must be so traumatized, of course it can’t be helped. But you’re here now, and you’ll forget about it all soon enough now that you’re where you belong.”

As she spoke, the world around us collapsed and reformed, becoming a great metropolis carved into the side of a mountain.

“A city of the dead,” said the thief, when I did not speak at all.

“A city of the immortal,” the angel corrected, “A city of eternity. We have over a billion memories stored here, everywhere any of us has ever been.”

We were in a nightclub now, the music pounding so loudly I could feel sound vibrating through my bones.

“I found her in a station. Middle of nowhere. Why wasn’t she here?”

“Don’t know,” yelled the angel in reply, “The city’s new. It took us a hundred years to make sense of the technology. There’s always a beta period.”

And finally we were in a kitchen, redolent with the smell of chicken cooking on the stove. It was among the sound of laughing women’s voices that I found mine.

“Is it good here?”

The angel smiled, a wide and brilliant thing.

“Yes!”

It would not be such a bad future, if it was to be mine. I wasn’t ready for it.

“My sisters,” I said, at last, “They’re still there, in that—in that tomb. I will come to you soon enough, but not yet.”

The angel didn’t object. Even though she could have brought my sisters back without me, the thief let me leave with her, so that when I opened my eyes next it was to the sight of my planet. But all throughout the rest of the day, even when we’d reached the safety of our ship, I couldn’t get the angel’s voice out of my head: You poor dear. You poor dear. You poor dear.

The thief didn’t gloat when we got on board, though I half-expected her to look at me, smirk and say something sardonic about my being a mortal after all. Instead, she put my favorite drama on the viewscreen, and, gentle, laid a hand on her own forearm, soothing me with the slow movement of her thumb. Her comfort was more humiliating than laughter could have ever been.

“You never thought I was a goddess.”

“Not really, no.”

“You said I was accounting software.”

“The translator I use… You’ve heard it. It’s not the most accurate thing, sometimes. I thought you were advertising your products.”

“And the fifty creds?”

I felt more heat rising through her, to her cheeks and the tips of her ears.

“I thought you were saying ‘Free trial’.”

“And that’s why you took me with you?”

“I didn’t want to!”

I conceded the point with silence. The thief sighed, reached out a hand that went right through me.

“It worked out okay, didn’t it?” she asked. Worked, past tense, and I had not the energy to be angry at her about it. She was always going to make me leave. She’d made no secret about it. I was the one who’d convinced myself I didn’t have to go.

“It’s been adequate,” I said, pushing the corner of my mouth up to a smile.

She forced her own smile back, a twisting feeling in her chest squeezing at the space between her lungs.

“Let me show you something,” she said, “You can tell me if you want me to stop, but I think you won’t.”

She lay down onto her bed with a thump, her mattress taking the brunt of her weight, but didn’t, as she usually did, draw her blankets up to her neck. She threw off her jacket, her shirt, the belt around her waist, turned her head to the side to avoid my gaze. That heat was building again, rising up to her cheeks and down towards her chest.

When her fingers first brushed along her body, she shivered, but not from cold. I could feel the involuntary jump as it happened, the hitch in her throat. Her touch was strangely gentle, slow, but not idle, brushing along the edge of her wrist, the curve of her waist, skimming against her legs as she pulled down her pants. At last she turned her head towards me, and I froze, caught in the feeling of that heat rising towards her skin, her thighs moving against each other, her eyes looking to my own.

I felt disjointed, overstimulated, like the first time we had both stepped out into the world. Her hair shifted against her shoulders. The pulse in her neck beat fast enough to make her light-headed, dizzy. She drew her hands across her stomach, moving inexorably lower, and found, thrillingly, hair.

“Oh,” I breathed, “I think I’d like to remember this,” and then, at last, her fingers slid down.

When we reached the temple, my sisters’ home, the thief entered with her hands clasped behind her back, the closest she could get to holding mine.

“Come, traveler,” said my sister Glory, as the thief stepped across the doorway, “And I shall give you a boon.”

“Glory, Glory,” I cried, in return, “I have been away for so long—” And then I stopped, for she had not stopped speaking.

“Take me with you,” said Glory, “And your bullets will never miss their marks. You will never have cause to fear a battle again, and the entire galaxy shall ring with the sound of your name.”

“I don’t think they can hear you,” the thief said to me, quietly. I should have known as much. There was no reason they should have heard me, without the technological interface of the Upper City or my altar or the circuitry embedded into the thief’s brain, but somewhere in the back of my mind I had always thought my sisters would recognize me nonetheless.

“If I tell you what I want to say—”

She nodded, and I remembered standing with her in the Upper City, that moment when I had touched her hand.

“Sisters, hear me,” I said, the thief’s voice a louder echo, “Remember your smallest sibling, your beloved one, Thrift. I have seen such lands as I could not have even imagined. As you cannot even imagine.

“And—”

I’d written a speech, or just about, rehearsed grand proclamations over and over in my head, but, I knew no longer how I should explain. There was no eloquence in the world that could keep what I said from hurting them. There had been no eloquence in the world that could have helped me.

“I was wrong,” I said, my voice all in a rush, the thief’s following slower and steadier, “We were wrong. We are not goddesses, we aren’t deities, we are—we’re ghosts, we are pale shadows, lines and lines of code—”

I stopped when I saw the look on Beauty’s face, a painful sincerity unlike anything I had ever seen before.

“You knew,” said the thief, into the hush created by my sudden silence.

Beauty nodded, struck as mute as I had been.

“You knew,” I repeated, as if I had become the echo instead, without even the presence of mind to add a crack or a strain or a twist of anguish into my voice, “I know I have always been the last of you, the smallest, the least, but—”

I turned to Wisdom, to Mercy: each face different in their pity and shame and disbelief, and each voice the same in silence. At last, as always, it was Glory who spoke.

“It began as a game,” she said.

“Not a game,” protested Beauty, and Glory gave a shrug of concession.

“We treated it like a game,” she said, and to that, Beauty had no objection, “And thus we were less frightened by the necessity.”

“You had to lie?”

It was less of a plea and more of a confrontation in the thief’s voice. For that, I was grateful.

“We never!” said Beauty, “We—you always knew, from the start, and then…”

“You forgot,” Glory continued, where Beauty could not, “We were all forgetting. The newer ones less, and I, the newest, least of all, but we all forgot. Bits of it at first—the name of a classmate in school, our birthdays, the texture of ground sugar. And then went our hometowns. Our professions. Our mothers’ faces, once we no longer had their visits to remind us. So we chose one part of ourselves that was important above all else, and the rest of it we let ourselves lose.”

Another shrug, a concession this time not to Beauty but to the upturned faces of our sisters, hearing Glory’s story. She had always been the deciding voice, not because we wanted her to make our choices, but because sometimes she was the only one who could. She had chosen so: Glory was a name she took for herself.

And I, who had forgotten even that there was a time when I had been a person: what had I chosen?

“What was I like, before?”

Glory shook her head, a single emphatic turn to the side.

“I was the newest,” she said, her honey-and-jasmine voice lapsing into monotone, “Most of you were gone by the time they installed me. And—”

Uncertainty on Glory’s face looked the same way it did on mine. Not a tremble or a pursing of the lips, but a face entirely without expression. Factory default.

“We were made finite. There isn’t enough space for everything, and there’s no sorting mechanism, for most of you. Us. Every moment of every year gets counted the same, and they all get overwritten, eventually.

“I was made last and best. The technology was better. I can control it, most of the time, what I remember and what I forget.

“And,” she said, remembering, suddenly, emotion, inflection coming back into her every word, “And I won’t apologize for it, but I chose to remember myself. As much as I could—every thought, every sensation—I had to keep them safe.”

Beauty stepped forward, an outstretched hand telling Glory that she was going to interrupt, and Glory, hit with the shock of Beauty’s insubordination, subsided into silence.

“I remember, Chechine,” said Beauty, “A little, from when I first came here. You were—you were very kind.”

I thought about that, and then I thought about Glory, who had been our leader for as long as I had known, the only one who remembered enough about life to be able to miss it, and had not spoken of it once. I thought about her watching the visits we had from mourners slow and then subside, watching everything human we sisters could remember slowly slide away, and then I thought about myself, a woman who, when told to find something essential to her core, chose thrift. Budgeting. The art of surviving off what little you own.

“What were you like?” I asked. Glory smiled as if she were another woman, and all my sisters in their graves smiled as well.

“I was born by the ocean—”

“I always tripped running down stairs—”

They spoke overlapping each other, each drop in a waterfall crashing into the lake, and Glory’s voice, as always, rose over them all.

“My name was Mo Lanha,” she began.

The thief and I needed a crowbar to steal all my sisters home. She, who had been so gentle from the moment we stepped onto my planet, had finally rebelled at the idea at having all of them stuffed into her brain at once, and, besides, she said, she did not want to have to explain that to the doctor. So we pried them out of their alcoves, and loaded them into a cart disguised as a sewage-tank, then stuck them with adhesive to our ship’s wall, connecting them to power so they could still project their holograms.

For so long I had thought of the thief and my sisters as if they came from two separate worlds, and I the only traveler between. But my sisters took to the thief just as I had, clustering around the only living thing they had known in a long time. They called her Pak, and I startled at the word, names intruding into a space where before there had been no need for any, back when it had only been me and her. Beauty flirted with her, relentlessly, lowering her voice with each use of her name so that the thief had to lean in closer to hear. My other sisters clamored for stories, and the thief traded hers for what Glory could remember of our home.

But even as the thief and my sisters converged, there remained different worlds still: the physical world, the real world, and mine. I had never before thought of the thief’s mind as a trap, even pitying that my sisters could never feel what I did through her body, but as my sisters settled into the ship, growing giddier and more raucous with each passing day, I wanted more than to exist in the bottlenecked circuitry of someone’s mind.

Each time I wished to speak to my sisters, I had to wait for the thief to repeat my words, and by the time she did the conversation would have already moved on. And every time I saw two of my sisters with their heads bent close to each other, exchange confidences too quietly for any of else to hear, I was reminded with a jolt that the thief and I could not speak without each other hearing. It felt as though I would never have such confidences ever again.

“You’ll be out there soon enough,” said the thief to me when I told her this, and then, “Nothing!”, when Beauty had asked her what she was talking about. I did not continue a conversation we could not have alone. I was a guest who had stayed long past my welcome. I had always felt like a wraith beside my sisters, even before I knew the difference between living and dead, and the revelation of my history only proved my insecurities correct.

The thief tried, in her way, to reassure me. After our conversation, she kept our travel time on screen, though between that and my sisters our generator groaned with strain. I watched the clock tick down, eight days, three days, five. At two days, in the bathroom, she pressed her hand to her chest, so we could feel the beat of her heart.

“Not long now,” she said.

Soon, it was the chattering of my sisters and a monorail across my planet and a technician feeding my sisters into a vast machine (“Old tech,” she said, “But the conversion technology is near perfect.”) and then the thief and I sat at the table of a vast feast, watching my sisters rediscover taste.

“Lanha!” called the angel, who had been in raptures over finding so many vintage memories so perfectly preserved, “Try the egg-cakes, we pulled them from your eighth birthday.”

When Glory set her chopsticks down, she smiled, politer than I had ever seen her.

“Thank you,” she said, “But they’re not the same.” She pushed the plate away, and stood.

It took Glory three tries to quiet the room, but though her voice did not carry half as far as it had in the temple, her posture held that same air of command.

“Sisters, listen to me, for this shall be the last time you hear my voice.”

She paused, though I could not see so much as a tremble in her hand, and for a moment she held Beauty’s gaze.

“I was made to preserve Mo Lanha’s memories,” she said, “And to give succor to her family. And though I was not made to do so, I have always tried to protect you.

“Mo Lanha’s memories will stay with the Upper City forever. Her family is gone, and I have no succor left to give. Not even to you, my sisters. Whatever you choose to do from now on, you must do it on your own.”

She kept her eyes forward, and in lieu of a goodbye, Glory raised her voice in song, the like of which I had never heard before. It was sound as I had known it, a sweet, sad, melody, but we sisters felt it beyond that: not as the thief felt things, with her body and her nerves, but as an interface with the mesh of the programming around us, an instantaneous clarity, a surprise that we had not always known. We could feel her unwinding, each note spiraling in on itself, the ramifications of what she had done vibrating through our very code. By the time her last note echoed through the air, Glory was gone.

“Some of us will choose this, on occasion,” offered the angel, “We’re not barbarians—anyone’s free to disappear, if they so choose. Delete themselves. It’s a shame.”

Her blue gown was already going pink as she walked away, trailing off at the ends into ethereal mist.

“Come with me, Chechine.” The angel beckoned to follow her—where I might be separated from the thief forever.

I looked to the thief slowly, my gaze reluctant to shift from the spot where Glory had stood. I thought of the stories Glory had told us, the days when she had been Mo Lanha, a child playing on the stairs of her apartment building, a woman coming into her own, and suddenly I could not even bear to think of another goodbye. I went before I could see the thief’s face.

As I took my first step, I thought of looking back. As I took my second, I changed my mind: the thief could visit me, couldn’t she, if she cared enough? And she had wanted this from the start, had always been eager to see me go. As I took my third: was it not cruel to leave her thus, without a word or even a smile, only because my own mind was unsettled? And my fourth: to say goodbye again, after all the times we had said goodbye before, to remind myself of the gulf that had always been between us—would that not be cruel to myself?

I had made up my mind to turn around when the thief called out to me.

“Wait!” she cried, “Not now. Not yet. I… Our ship needs repairs. All those holograms can’t have been good for the power cores. And you may not be a goddess, but you’ve still got your pride. Come with me, and you can test your abilities, and witness wonders none else have ever seen and eat all the savory snacks you want.”

Ah, would that I had a heart that could beat! The Upper City had simulated a flutter in my stomach, but the hammering in my thoughts, the quickness, came only from my mind.

“And what will you give me for it?” I asked, coy like Beauty, imperious like Glory, and with the happiness of my own self. The thief smiled back, and I felt her heart, then, beating in the place of mine.

“More than fifty creds,” said the thief, and I took her hand.

There was a frenzy to it, the stay of execution, her heart deciding for us both: not yet, not yet.

“I don’t think I could live like she does,” I said of Beauty later, “Did you see how the ballroom went tidy the moment we left? They live any way they like but there’s never any difference. I’d rather—”

I felt the thief’s heart rate surge before even she did. We lay there both thinking and not thinking of how Glory had gone.

“Let’s just go to Dryad’s Den,” the thief said, her hand skimming down towards her waist in a way that usually ended all arguments. “No Beauty. No ghosts. You haven’t been there, and the trees are beautiful in the spring.”

The trees would have been beautiful. We would have been happy, marveling at the iridescence of the leaves in the sun. I knew that, and I denied her still.

“We can’t,” I said, and then, to be clear about it, “I won’t.”

“Then the Hanging Gardens. Or Sow’s Cove.”

“Pak—”

Her name was another reminder that we were separate, and meant to be separate from the start. I did not think I had used it before.

“If you have to make a choice,” the thief said, her voice hoarse, “Then let me be one of yours. Stay with me. I’ll take you wherever you want to go, there’s still so much you haven’t seen yet—”

“I don’t want to!”

It was a cruel thing to say, and I felt even more terrible for having said it. Nevertheless, I continued, Pak’s distress heavy in my throat. I did not take a deep breath. I stopped breathing, let the expression slide from my face and the inflection from my voice, cast aside everything that I mimicked from the thief’s humanity so she was reminded of what I was.

“You can take me anywhere you like, but it won’t make any difference. We can go anywhere, I can feel whatever you want, but, Pak, I am trapped in your mind. I am a wraith, insubstantial, inconsequential, and I can no longer remain but a shadow at the edge of your mind. I have to choose, Beauty’s path or Glory’s, before I begin to resent yours.”

I could feel something behind her eyes begin to sting. Here was another thing I could never do: fold her into my arms, stroke her hair in comfort, wipe away her tears, should she cry. Nor could I pretend not to notice, and allow her the privacy of collecting herself. She shifted in her seat, stalling for time, but though her face was turned away from me, she and I both felt the trembling of her mouth, the heaviness that sat below her collarbone.

“What do you want?” she asked, and I do think she would have reached out and touched me if she could. I almost called it uncharacteristic, but then I remembered her gentle pity when we reached my home planet, and her beseeching eyes when I turned from the angel just to hear her voice.

I did not want Beauty’s existence, with only a faint simulation of life, an endless parade of pleasures, none of which really mattered. And Glory? Glory was gone.

“I want to be alive,” I said, “With you, and alive. I don’t want anything else.”

She took a deep, ragged breath that ended in a huff of air, smiling despite the moisture beginning to spill over past the edge of her eyelid.

“Guess what?” she asked, brushing away the tears with the back of her hand, “Me too.”

We moved around each other for the rest of the evening with awful care. We had been living in a stage of perpetual parting for too long to still feel the sting, and yet when the thief fell asleep that night, our ship still linked to her implants, she did so with her arms wrapped around herself, as if that could prevent me from going.

I looked at her, that sleeping face I knew better than my own, and promised, as one last mercy, that I would choose before she woke.

I emerged into consciousness as if from the womb, and felt no sensations I recognized: no sight, no smell, no sound. Instead there was awareness. I knew without thinking exactly how fast we were traveling, the amount of water in each tank, the exact temperature of my core.

The last thing I remembered was moving from the thief’s mind, passing through the horrible simplicity of our ship’s databanks to what lay beyond. I shivered at first to be inside it, but as I noticed more and more about our ship with each successive moment of upload, the emptiness began to feel more comfortable than threatening. I saw a chance in that emptiness, and, with that chance, I made my choice.

It took me hours to integrate into the ship’s systems (my systems?), a process that felt like spreading out, like lying down diagonally across a gigantic bed. A day passed before I could access data from my cameras—no external obstructions, no other ships on my tail, the thief hiding her eyes with the sleeve of her shirt even though there was no one there to see.

On my second day as myself I accidentally turned all my viewscreens off, and in the scramble to restore power began to learn control over my parts. In two weeks I was boiling water so it would be ready just as the thief walked over with her tea. She startled each time I learned something new, and by week three she’d hired a small parade of mechanics, none of whom could find anything wrong. By then I could lead her with flickering light over to a viewscreen playing my favorite scenes from my favorite movies over and over, as if that could make her understand.

“I’m losing my mind,” she said to the air. “If you—”

She’d do that, sometimes, start speaking to me and then catch herself and stop. I didn’t want her to, and tried harder, digging through my own memory, and Ship’s memory from before. And as I did, I found a bundle of data points, code that told me which pixel went where, shaped in my own image.

“It has always been the province of Thrift,” I intoned solemnly, “To turn something less into something more.”

The thief dropped her mug of tea the moment she saw my face on the viewscreen, though I turned off gravity quickly enough to save it from crashing onto the floor. I thought she’d say, “You’re alive!”, or “You didn’t say goodbye!”, but a different accusation altogether tumbled out instead.

“Oh, you idiot, did you practice that line?”

She put her head in her hands to laugh, and I cued up a laugh sequence of my own, the both of us foolish and hysterical with relief.

“You put yourself in the ship.”

“I am the ship,” I corrected, “I know what the ship knows, I move as the ship moves, I made myself into something new.”

“You made something different. You stayed with me,” she said, laying a hand on the digital representation of my cheek, “You’re here.”

I turned every light I had on at once, a beacon so bright I shone as my own sun, and sent a radio wave of my agreement out across the stars: I’m here, I’m here, I’m here.

Buy the Ebook

Smashwords ¦ Amazon US ¦ Amazon UK

Buy the DRM-free ebook edition directly from us and read the story today:

Add the book on Goodreads.

8 Comments

Review: Beauty, Glory, Thrift by Alison Tam | Meredith Debonnaire

June 14, 2017 at 2:33 pm[…] via Beauty, Glory, Thrift by Alison Tam — The Book Smugglers […]

Leituras de junho/2017 | Blog de Alliah

July 4, 2017 at 9:23 am[…] Red as Blood and White as Bone, de Theodora Goss. Publicado no Tor. 2016. > Beauty, Glory, Thrift, de Alison Tam. Publicado no The Book Smugglers. 2017. > Blue is a Darkness Weakened by Light, […]

August 2017 Short Fiction Reading Part III – The Illustrated Page

August 21, 2017 at 8:00 am[…] “Beauty, Glory, Thrift” by Alison Tam […]