Welcome to Smugglivus 2015! Throughout this month, we will have daily guests – authors and bloggers alike – looking back at their favorite reads of 2015, looking forward to events and upcoming books in 2016, and more.

Who: Clare, who blogs about books and movies at The Literary Omnivore, is a first reader for Strange Horizons AND one of the new co-editors at Lady Business.

Queer lady geek Clare McBride was raised by French wolves in the American South. Exposure to toxic levels of VH1’s I Love the 80s, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and Mystery Science Theater 3000 as a preteen mutated her into the woman that we know today; an entity all about fandom, feminism, pop culture, speculative fiction, queer history, and any other way those words can go together. There is no cure for her addiction to run-on sentences.

Please give it up for Clare, everybody!

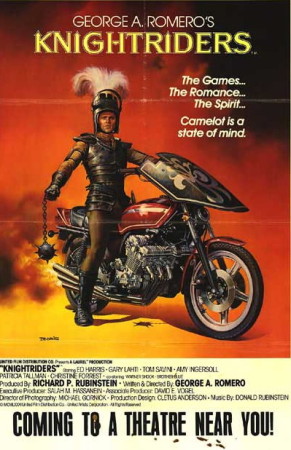

“Camelot is a State of Mind”: The Charms of George A. Romero’s KNIGHTRIDERS

As someone who didn’t see Star Wars until her twenties (I do not count watching the Special Editions as a teenager, because they left me ice cold) and still hasn’t seen either The Sound of Music or The Wizard of Oz (I was raised by French wolves), I am well-used to being on the receiving end of “How have you not seen this movie?!”

I realize that this question is an expression of the questioner’s love for the movie in question, but it’s still kind of a jerk move. There’s lots of reasons people haven’t gotten around to certain movies! Luckily, I’m hearing it less and less, as I see more movies and people seem more aware of its jerk move nature. One of the greatest panel experiences of my life happened at Dragon*Con one year, when a panel on the films of 1982 opened with the moderator stating that nobody was going to be shamed for not having already seen something, but rather celebrated for having it in their future.

Obviously, I try not to ask that question. My substitute colorist told me my reaction to her having never seen (“Oh! Well, they’re fun, but you don’t have to.”) was the mildest reaction she’d ever received. But the 1981 film Knightriders is the kind of movie that makes me want to ask that question. A lot.

But I do know how you have not seen this movie, kittens. It’s an answer in three parts. One: Knightriders is an outlier in director George Romero’s filmography, since it doesn’t involve zombies or other horror elements. (But it’s not the only non-horror film in Romero’s back catalog, lest we forget the romantic comedy There’s Always Vanilla.) Two: There’s never really been a big market for dramas about Renaissance Festivals. Three: It’s long been a pain to get a hold of, although it’s now blessedly available on iTunes. (I originally saw it thanks to the good graces of the Denver Public Library system. Thanks, friends!)

And that’s a shame, because Knightriders is a gem of an sf-adjacent film.

Knightriders is about a Renaissance Festival troupe helmed by Billy “King William” Davis. Billy originally founded the troupe as an alternative society to the world around him, one where he can practice his noble ideals and his knightly code and live a life that he believes in wholeheartedly. While the other members of the troupe respect and love him, they don’t adhere to his code as closely or fanatically as he does. Nonetheless, the troupe is a merry, loving found family. But by the time the film opens, their festival has become successful enough that they need to start thinking about the troupe less as an collective and more of a business if they’re going to stop living hand to mouth. But Billy is adamantly opposed to any change, leaving everyone else conflicted and worried about the future of the troupe.

And that’s largely it. At two and a half hours, Knightriders is languid and unhurried. The troupe goes from town to town in Pennsylvania, setting up shop for the weekend, and, largely, talk about their feelings and their problems. A characteristic scene is the one where Merlin, Steve, and Bagman get the usually abstinent Billy high in a forest to keep him from running himself ragged. (That is the most late seventies thing that has ever happened, by the by.) They end up talking about the conflicting drives for idealism and survival. While they don’t convince Billy and Billy doesn’t convince them, the film lets the conversation play out.

It’s hard to convey the film’s fascinating essence in total. Instead, here are some of Knightriders’ charms to entice your viewership:

There’s No Villain

Morgan, the Black Knight, seems, at first blush, the perfect villain: he cares more about bikes and girls than knightly ideals, openly advocates bribing cops, and jumps on the first entertainment agent who comes calling. But his adventures outside of the troupe only teach him that what he had back home was more valuable than what Hollywood could provide. While the troupe does battle with skinheads and crooked cops, the only antagonistic force really seems to be Billy’s dogged devotion to his ideals at the expense of others. No one’s really at fault here, but everyone’s best-intentioned actions brought them to this crossroads nonetheless.

The Ladies of the Troupe

There are three major female characters in Knightriders: Linet the queen, Angie the mechanic, and Rocky the lady knight. And they’re all fantastic. Linet, Billy’s Guinevere, seems initially fated to wring her hands in the background, but once she steps up, she turns out to be a shrewd, loving leader. When Billy orders the troupe to stay overnight on the road while he white knights in jail, Linet takes control in the pragmatic way that the troupe could use as a way forward. And she even outright states that she loves the troupe more than she loves Billy.

Angie is a plainspoken grease monkey, both a genius with bikes and hopelessly in love with Morgan. But she’s aware of who he is, what he does, and what kind of influence he has on her. She loves Morgan (and they are bonkers cute together), but she refuses to rise to his bait when he tries to exploit this by luring her away from the troupe that accepts her as she is.

And Rocky? Rocky is amazing. In a cast of characters who all suffer some doubt about who they are and/or their place in the world, Rocky is, to quote Stacker Pentecost, a fixed point. She’s the de facto leader of the knights, leading them into battle against skinheads at one point. She’s a fierce competitor in the jousts as well as a graceful loser. And everybody in the troupe fully accepts that Rocky is the coolest person in the troupe. Even her friendly rival knows that Rocky, in his words, kicks ass.

Pippin and Punch

Pippin, the troupe’s announcer, is one of the earliest positive queer characters I’ve found so far in film. He’s an important and beloved part of the troupe; even Angie needling him about his sexuality seems more sisterly concern than baffled heterosexual meddling. I mean, it’s not great behavior on her part, but they talk about how it wasn’t great, because the film sympathizes equally with both characters. And Pippin ends up finding love in the troupe with one of the tumblers, the strapping Punch. Pippin first notices him when Punch comes to defense after not talking for the first half of the movie, and Pippin’s look of both dumbfounded attraction and “You can talk?!” is pure romantic comedy.

They’re cute, they’re happy, they’re accepted, and neither of them die in a movie from the eighties. Treating queer characters like people: whatta concept!

Diversity

In 2015, we’re still dealing with people baffled by and openly hostile to black Stormtroopers and people who complain that diversity in fantasy and historical fiction is political correctness gone mad. In 1981, Knightriders features three black male characters (with lines, even!) and a Native American character. It’s not a paragon of representation by any means, as it plays into Magical PoC tropes with both Merlin and the silent Blackbird, but it is nice to be able to watch a thirty year old movie that doesn’t take place on that weird planet of just white people most mainstream films seem to be set on.

Hoagie Man

The greatest thing about watching older movies is seeing how they function as a time capsule, and Knightriders is no exception. It’s late seventies, very early eighties Pennysylvania at its best. The hair! The clothes! The glasses! On the story’s forays into the regular world, it’s like, well, Obviously, this isn’t intentional, but it’s so hard to get a good feel for what regular people—or regular Pennsylvanians—looked like at the dawn of the eighties that this is a surprising benefit.

All of this is epitomized by Stephen King’s scene-stealing role as Hoagie Man (and Tabitha King, his wife, as Mrs. Hoagie Man). That’s right, horror novelist extraordinare Stephen King turns up to eat hoagies and talk smack, and he’s… got plenty of hoagie.

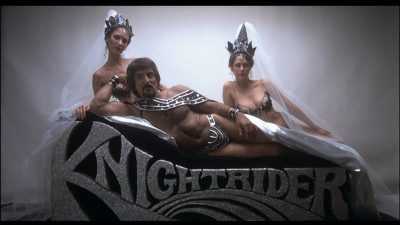

This Scene

You’re welcome, Internet.

Motorcycling Jousting!!!

I’ve buried this lede well on purpose. Motorcycle jousting is the raddest, most visible, and least important part of Knightriders. But it’s an integral part, with motorcycle confrontations and leisurely bike trips down the road making up a fair portion of the runtime. Even without the gut-punch association of motorcycles with the counterculture that was present in the seventies, it’s just cool to see knights on motorcycles. This is also a great way to lure your gearhead friends into watching it with you, if they are so inclined.

Knightriders is by no means perfect. The action set pieces are filmed perfunctorily in a way that has not aged well, did I mention the magical PoC trope overtones with Merlin and the Blackbird (who is only credited as “the Indian”: ouch)?, and the film’s youngest female character, the charming Julie Dean, is abandoned to her abusive household at the end of the film.

But it’s nonetheless transfixing. It’s not a good bad movie, to borrow the rating system of bad movie podcast The Flop House; it’s a good movie whose greatness is visible in fits and snatches. It’s easy to see where things could have been tightened and fixed, but I find that I don’t really mind once I’m an hour and a half into the movie.

You can rent Knightriders from iTunes in both standard definition and luxurious high definition. There’s a 2000 DVD release and a 2013 Blu-Ray release, which looks gorgeous. I am considering purchasing a Blu-Ray player for this movie. That’s how much I love this movie.

5 Comments

Martha

December 28, 2015 at 3:35 pmI just … I cannot BELIEVE I didn’t know this movie existed until now. Why is the known world not shouting about it, like, 24/7??

*puts it at the very top of the To Watch in 2016 list*

Dr. Humpp

December 30, 2015 at 12:26 pmWhat a great, loving article. This is one of my favorite movies ever

The Week in Review: January 3rd, 2016 | The Literary Omnivore

January 3, 2016 at 8:36 am[…] The Book Smugglers kindly invited me to contribute to Smugglivus, so I wrote about how much I love … […]

Book Blogger Appreciation Week: Recommendation | The Literary Omnivore

February 17, 2016 at 7:04 am[…] And it is—it is so dark and so bleak and so good and so necessary. I don’t want to say that the subject matter is so delicate that I would only read this if someone I trusted recommended it, because feminist dystopian fiction is a very real genre. But it was really nice to read a review of the book from a quarter that got what O’Neill was trying to lay down, whether or not the blogger liked it or not. (Ana liked it, obviously.) One of the things that I really appreciate about book blogging is that you get a taste for other people’s tastes, which makes recommendations a lot less fraught. I know that I can trust the Book Smugglers for feminist-minded sf, and I’m not just saying that because they let me yell about Knightriders for Smugglivius. […]