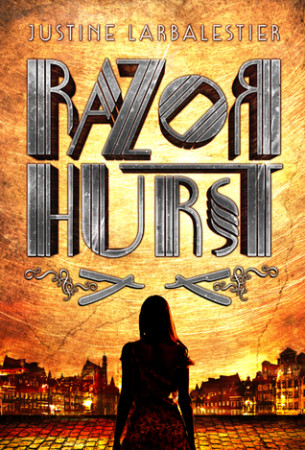

We are thrilled to unveil an excerpt from Justine Larbalestier’s newest (and most highly anticipated) novel, Razorhurst.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Razorhurst by Justine Larbalestier

Razorhurst by Justine Larbalestier

Published by Soho Teen

Available March 3, 2015

The setting: Razorhurst, 1932. The fragile peace between two competing mob bosses—Gloriana Nelson and Mr Davidson—is crumbling. Loyalties are shifting. Betrayals threaten.

Kelpie knows the dangers of the Sydney streets. Ghosts have kept her alive, steering her to food and safety, but they are also her torment.

Dymphna is Gloriana Nelson’s ‘best girl’, experienced in surviving the criminal world, but she doesn’t know what this day has in store for her.

When Dymphna meets Kelpie over the corpse of Jimmy Palmer, Dymphna’s latest boyfriend, she pronounces herself Kelpie’s new protector. But Dymphna’s life is in danger too, and she needs an ally. And while Jimmy’s ghost wants to help, the dead cannot protect the living . . .

THE EXCERPT

They called Miss Dymphna Campbell the Angel of Death because every man she was with for more than a couple of days wound up dead.

It started as a joke.

But some believed that she really was.

Dymphna believed that she really was. Dymphna knew that she really was.

Dymphna Campbell should have been dead. She should have died with her mother and her sisters. But she escaped death, only to live the rest of her life tainted by Death.

Dymphna Campbell saw ghosts. Had done so since before her name was Dymphna Campbell; from the moment she came into this world. Her mother’s parents died the day she was born. The very hour she was born. In the same house. Spanish flu took them both.

Death swarmed around that house. Took the three siblings that followed her.

Spared the twins: Vera and Una.

Until the night her father did for them and did for her mother too. He used an axe.

He tried to do for Dymphna-who-was-not-yet-Dymphna too.

She did for him.

With a knife from the kitchen. She didn’t know what she was doing.

It was the middle of the night. Still, balmy. She hadn’t been able to sleep. Tiptoed down to the kitchen, holding her breath as she passed her parents’ room, poured herself some milk. She heard one choked-off scream. She dropped the glass. It must have shattered.

Heard footsteps, a slammed door.

There was a carving knife in her hand. Sharp, it was. Isla kept all the knives sharp. Fewer accidents that way, she said.

Her father was there, in the kitchen, axe held high, blood all over him, dripping from his chin, from his hands.

She remembered wondering where the axe had come from. They had no fireplace. No wood to chop.

The carving knife was in her hand, and then in him.

She didn’t remember how she did it. How she knew to push up under his ribs. But she did. Again and again. She could not say how many times.

Her father dropped the axe. Tried to bring his hands to her throat. Fell.

There was blood everywhere.

The kitchen was bathed in it. She stepped over her father, knife in hand, followed the blood along the hall, up the stairs, into her parents’ bedroom where her mother lay in blood-soaked pieces, her eyes still open.

She tried not to wonder how that was possible. She closed them, kissed her mother good bye, followed her father’s bloody footsteps to the twins’ room.

Vera and Una looked like tiny, red, broken dolls in the middle of their bed. Four years old. She could not bring herself to touch them. She blew kisses at them and turned away. She left home to escape the place where they died, where she almost died.

She left because it could never be home again. She left because, as she walked down those

stairs, her father rushed at her, arms aloft as if he still held an axe, as if he still had the power to kill her. Even though he was dead and would always be dead.

He ran straight through her.

Then the ghost of her father screamed that she was a no-good slut. Screamed at her dead, unmoving mother that she was a foul temptress. Like mother, like daughter, he roared, face turned dark. Then he screamed the same at tiny Vera and Una.

As he had when he was alive.

She ignored him as she had tried so hard to do when he was alive. She would close her eyes and pretend he wasn’t there. It was much easier now that he was dead. He couldn’t lay a finger on her anymore. She could ignore him with her eyes open.

Dymphna put the knife down while the ghost of her father screamed that she was trash. She went to the bathroom and washed and washed and washed. She had to fill the tub three times before it drained away with no trace of blood. Her father stood over her calling her a dirty whore, pointing to the parts of her body that offended him most.

She went to her bedroom, careful not to step in any of her father’s bloody footprints. The door had come off one hinge. Bloody handprints were streaked around the knob. She dressed and packed one small suitcase. Swung her warmest coat over her shoulders, though it was summer. It wouldn’t always be summer.

She pulled all the money from her father’s wallet, from her mother’s purse, from the jam-jar hidden behind the breadbox, while her father called her a thief and a liar.

Almost fifty pounds in all. It seemed like a fortune.

Her mother and the twins did not become ghosts. For which she was grateful. She could not have faced them enduring her father a second longer. Or the ache of seeing Vera and Una unable to hug or kiss, unable to pick flowers from their mother’s beautiful garden. Her mother’s arms going through her… It would have been too much.

She could not have pretended not to see them; she could not have borne leaving them.

She left home before dawn not knowing where to go.

Her father followed her down the hall to the front door, across the porch, where she bent to put her keys under the empty flowerpot.

Down the path to the front gate, past her mother’s peonies, irises, roses, lilies, delphiniums, sweet peas, pansies, sunflowers, larkspurs, Queen Anne’s lace. Dull in the darkness, but come dawn the garden would sparkle with whites and yellows and oranges and pinks and blues and purples. People stopped from miles around to admire her mother’s garden.

Her old man walked with her every step of the way, even as she paused at each new cluster of flowers to bend and inhale. She loved the sweet peas best. They smelled exactly as fresh and sweet as her mother.

She was sure she would never smell their like again.

Those bloody flowers, her father snarled in her ear.

She shivered with fear that he would haunt her forever. But she opened the gate and stepped out of her mother’s garden alone.

She took a few more steps along the footpath beside her mother’s white picket fence. Her father walked through the flowers on the other side, his face contorted.

At the edge of the property, she turned, looked past him, at her mother’s beautiful cottage, surrounded by flowers, knowing she would never see it again.

That’s when she would have cried if she had not long since learned that it did no good.

She turned away, walking towards the water. She would walk the whole way. Not wait until the buses started running at five.

Her father screamed one last thing: But I loved you, he bellowed, calling her by her longforgotten name. I loved you all.

She told no one. She renamed herself before she boarded the first ferry of the morning. Dymphna for the saint whose life was all too like her own. Campbell because it was the name of the athletics coach at school who had encouraged her to run, far and fast.

Dymphna Campbell sat on the ferry bound for the city, watching tiny waves break against the hull, seagulls diving down across the water searching for fish, and wondered where to go, what to do. Her left leg began to shake.

Dymphna’s father was the first one to touch her. He was the first one to die. He was the only one she didn’t want to touch her, the only one she killed herself. She did not know if her father’s death had made her the Angel of Death or if she was born marked. Perhaps it didn’t matter.

All Dymphna knew was that Death had been with her from the beginning. She saw Death everywhere, and no one else could. But she hoped there was someone else.

Then she saw the crazy old man living on the streets in the Rocks. He talked to ghosts. They taunted him. Here was proof of what she had always thought: acknowledge the ghosts and they drove you mad and out onto the streets. Might as well be a ghost yourself.

Better to keep them at arm’s length. Avert your eyes.

Then Dymphna saw wee Kelpie, who might have been a darker Una or Vera if they had escaped their father, if they’d had more years of life, if they had not died. So many ifs.

Dymphna saw Kelpie talking to ghosts and knew she had to save her.

Excerpted from Razorhurst by Justine Larbalestier (March 3, 2015)

Razorhurst is available now! Get your copy below, or visit Soho Press for more.

2 Comments

Nikki Egerton

March 10, 2015 at 8:34 amHooked already!

Hebe

March 11, 2015 at 6:42 pmWow.