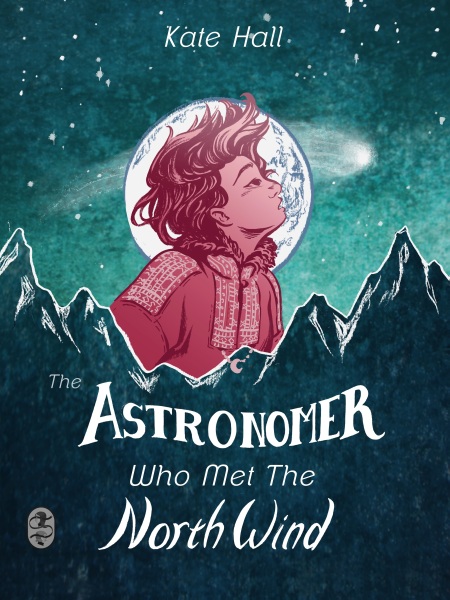

The Astronomer Who Met The North Wind by Kate Hall

Published 12/2/2014 | 3,312 Words

Down there, the North Wind whispered in her ear. Down where I don’t blow so fierce, there you will be able to observe your stars.

Once upon a time, high in the northern mountains, there lived a great astronomer and his daughter. Though Minka was clever and loved the stars as much as her father, no one believed she would ever become an astronomer—for this was not a path meant for little girls.

But on her twelfth birthday, the North Wind blows at Minka’s window, beckoning her to leave safety and warmth of her bedroom. With her father’s telescope and journals strapped to her back, Minka embarks on the adventure of a lifetime, under the starry night sky.

High in the northern mountains, where for six months of the year the sun barely graced the sky, there lived a great astronomer. He was much sought after, both for his knowledge of the cosmos and his practical development of telescopes, which he was always refining to better see the sky. He was loved by his students and colleagues alike, and considered one of the finest scientists of his age.

The astronomer, being an eligible man and scholar, married a young woman and they had a daughter, Minka, as smart and curious as her father. She loved the elegant simplicity of geometric proofs, created her own puzzles, and as she grew she impressed her parents with her cleverness.

But when Minka was six, her parents went out on an expedition, and in the bitter winter cold her mother took ill with an infection of the lungs, and died.

Minka mourned her lost mother with a child’s ferocity. The astronomer, unsure how to comfort his daughter and distracted by his own grief, tried everything he could think of to no avail. At last, he brought his reflecting telescope into Minka’s room, and angled it at the clear night sky. As she gazed at the glittering stars through the telescope’s eyepiece, Minka’s thoughts drifted away from grief and resolved on a new singular goal: Minka, too, would be an astronomer.

But whenever she spoke of her plan, people smiled and patted her on the head.

“What a sweet idea, wanting to be like your father!” they said. “But you’ll probably change your mind, you know. Children don’t ever know what they really want to be when they grow up.”

Even her father, who let her keep the telescope in her room after that night, chuckled when she told him and ruffled her hair. “We’ll see, darling. You’re young yet, you may want to do something else.”

Minka didn’t like it when people spoke so. I know I’m smart, she thought, and I know what I want to be! It annoyed her that people thought she didn’t know what she wanted just because she was young. So she saved her money to buy books on distant planets and galaxies, plotted constellations on her bedroom walls, and observed astral phenomena. Still, despite her studying and dedication, when her father went into the field and Minka begged him to let her come along, he always declined.

“Going out in the dark is dangerous for a child,” he said, for the fear of losing his daughter like he had lost his wife weighed heavily on him. “Besides, it’s not very interesting! Much of the time you are waiting in the cold for something that isn’t there. You would be bored.”

“You don’t know that.” Minka crossed her arms. “I think I’d find it fascinating.”

But her father only tugged a curl of her hair with a fond smile, and left her to her books and telescope.

For her twelfth birthday, the astronomer gave Minka new clothes, a jewelry box, and a spun-glass model of the night sky, dyed dark blue and filled with silver air bubbles for stars. He gave her only one book on constellations, and it was an introductory text for children with more pictures than words.

“Are you pleased?” he asked her. A cake shaped like the constellation Cygnus sat between them, the gold icing stars twinkling in the lamplight. “I asked some of our friends in town for advice. Your mother would have known what to get you, were she here”—he offered a rueful smile—“but I was assured that these would be perfect for a young lady.”

Minka turned the glass model over in her hands and set it aside. “They are very…pretty,” she said at last, because she knew her father had tried, and that he meant well. “But I didn’t want these things. All I want is to go out to make observations with you.”

The astronomer wrung his hands. “But Minka—”

“Please?” She pointed at his gear and field telescope—his latest refinement, with thin parabolic mirrors and long legs that could fold—stacked by the front door. “You’re going out soon, aren’t you?”

The astronomer sighed. “I had thought to go out, yes. A few nights ago I thought I glimpsed a comet, and wanted to see if it was just an anomaly…but the weather is too poor tonight. Besides, it’s your birthday! I wouldn’t want to miss that.”

Minka leaned forward. “A comet? A new comet? But that sounds amazing! Please let me come with you—we could look for it together.”

Her father reached around the cake and took her hand. “Darling, the weather is wretched. You would get soaked, and cold. Astronomy isn’t a glamorous job. I know you like the idea, but it’s not something you really want to do, I promise.”

Minka stared at him for a moment, then withdrew her hand and pushed back from the table.

“Thank you for the gifts,” she said in a low voice. “But if you won’t take me out with you, you might as well not give me anything.” She left the kitchen before her father could see the tears on her cheeks.

In her bedroom, she threw open her window, letting the air cool her flushed face. Clouds scudded across the sky and the mountains stood guard around her, round and ancient, cradling the half-visible stars. Minka leaned on her windowsill and wiped her eyes. Her stomach churned, bitter, and even when she heard her father call her name softly through the door, she let her angry silence answer for her. She reached for her telescope, always pointed skyward, and sniffled; there would be no stars tonight. She watched the clouded sky, waiting for it to clear, until she fell asleep at her window.

Minka.

The wind blew, a sudden, cold slap against her face, jerking Minka awake. Over its whistling, Minka heard again what had woken her: a voice calling her name. It didn’t sound like her father. It sounded like pine needles crushed underfoot, like snowflakes whispering against the windowpane. Minka.

“Who’s calling me?” She turned toward the door, but it remained closed. She turned back to the window, but no dark silhouette marked the snow to accompany the whispering voice. The stiff wind blew snow off the roof overhead and it spiraled through the window, catching on her sweater where it twinkled and melted.

I, the North Wind, call you, the voice said, and another cold breeze ruffled Minka’s hair. Why are you angry, Minka who gazes at the stars?

Minka crossed her arms. “Who says I’m angry?”

Ice stung her cheeks, and the North Wind laughed. Minka pursed her lips and let her arms drop.

“Fine. I’m angry because I want to be an astronomer, and no one believes me. I’m tired of people telling me I’m too young to know what I want to be when I grow up, or that astronomy is too hard or dangerous for me.” She drummed her fingers on the windowsill. “If I could go out there and show them what I can do, no one would ever doubt me again.”

And what is stopping you? The North Wind teased the blankets on Minka’s bed. Look up, stargazer!

Minka did, squinting against the snow’s glare. A break in the clouds showed the half-moon, and it edged the mountains in silver. The lower rises, flattened from years and weather, looked like stooped shoulders, the higher mountain peaks like hunched heads.

Do you see those plateaus? The North Wind said. From there, you could see every star in the heavens.

Minka leaned on her elbows. She could see the closest plateau, a black outline against the night sky. She thought of her father’s gear, waiting by the door. She thought of the mystery comet, somewhere out in the sky. If she found it, if she could glimpse its position in the sky, maybe, just maybe, people would listen. She grabbed her hat and jammed it over her dark hair.

“Let’s go, North Wind.”

She let herself out the front door, taking her father’s bag, his notes and tools, as well as the telescope strapped to it with her. The bag was large and heavy, and even after she emptied it of extraneous things, like extra socks and blank journals, Minka still staggered to adjust its weight on her shoulders. The North Wind gusted around her, stinging her cheeks and making her eyes water. The snow drifted like fog, but she could make out the footpath stretching from their property, tamped down from her father’s frequent trips. Her boots crunched as she began to climb.

She ventured through scrub and snow, over slippery rocks and frozen lichen. Her shoulders ached, the straps from her father’s bag digging into her muscles, and the cold chewed through her coat and sweater until her arms and legs burned with it. She pulled her scarf up over her mouth and nose, but soon her breath iced the fabric. All the while, the North Wind hissed around her, goading her onward. Climb! Climb! Show them what you can do!

Minka gritted her teeth and pressed on. The trees began to thin, and overhead starlight peeked through the clouds, glass shards poking through thick wool. The air tasted thinner up here, sweeter, and the powdery snow gave way to hard, frost-laced rock and moss. She crested the last rise, and a flat, uninterrupted plain stretched out before her. The plateau. Minka ran to the edge, breathless, and gazed down. She could see her house, small as a child’s toy, nestled below, a curl of smoke drifting from the chimney.

“Look!” She shouted down at her father, though she knew he couldn’t hear. “Look up here!” She laughed and clapped her hands, warmed by her triumph, then turned to deposit the bag and set up the telescope.

But the wind blew even harder up here, ripping the hat off her head and tangling her hair in her face. Her eyes teared when she tried to look up, and though she wiped and blinked them, she couldn’t get them to stay clear. She couldn’t look for the comet like this.

Down there! The North Wind cackled, and a cold gust struck the side of Minka’s face. She turned away from its violence, and shuffled against the wind to the far end of the plateau. The slope down this side was steep, and it gleamed with ice and rock. At the bottom, a small lake had carved a clearing in the evergreens, its frozen surface reflecting the sky above. The bushy trees stood tall in all directions, their needles still.

Down there, the North Wind whispered in her ear. Down where I don’t blow so fierce, there you will be able to observe your stars. The clouds parted, as if to prove the North Wind’s point, and the frozen lake glowed.

Minka studied the incline, and reached back to touch her father’s bag. The slope looked tougher than the one she had just climbed, and going down her balance wouldn’t be as good. But the unblemished snow below sparkled, and somewhere in the sky a comet begged to be found. The North Wind shrieked around her as she considered her descent. Go, go, go! Down, down, down!

Her first step made her slip onto one knee, the pain jarring up the bone. Minka tried to climb down at an angle, grabbing at whatever brush or handholds she could find, her boots struggling to find purchase on the slippery ground. Her father’s bag slipped, pulling her overbalance, and Minka paused to correct herself. All around her, the North Wind howled, urging her on.

She stepped down again and her foot shot out from under her, foothold crumbling away. Minka toppled forward, felt her father’s bag swing up over her head, and then she was sliding, careening down the slope. She tried to dig her hands into the snow to slow her helter-skelter descent, but the stones snatched off one glove, then the other, ripping at her hands so she left scarlet trails behind. She heard a tearing noise, and metal flickered out of the corner of her eye. The telescope! Her father’s bag sailed past and she grabbed blindly, her hand closing on something smooth and cold. She folded over the telescope as the snow rushed up to meet her and the world became a dizzy sky-snow-sky-snow tumble.

At last, she rolled to a halt: dizzy, soaked, and freezing. For a moment, she lay silent in the snow, listening to her heart thud in her ears and feeling the cool cylinder pressed against her ribs. Then she pushed herself up onto her hands and knees. Her hands bled and stung in the deep powder, and she flexed them, wishing for her gloves. Then she sat up and scanned the clearing.

Her father’s bag lay a few feet away. One of the straps had torn off, ripping a hole in the side. Books fluttered in the breeze, scattered across the clearing. She gathered them up and put them back in the bag, then went back to the telescope, holding her breath. The eyepiece had detached and was buried in the snow, and one of the foldable legs had bent. Minka dusted off the eyepiece and let out a breath of relief—but for some scratching along the edge, it seemed unharmed. The rest of the telescope, too, seemed to have escaped unscathed. She had made it. And now she would see the comet! She reattached the lens, searched for a suitable surface and finally brushed one of the lakeside rocks clear of snow. She unfolded the tall legs, using branches to support the bent one, and looked through the eyepiece eagerly at the night sky.

Nothing.

Minka looked up, disbelieving. Clouds, thick and low, covered the stars once more.

There are your stars! The North Wind rushed down the mountainside, howling with laughter. Minka, her clothes wet and ruined, shivered. Didn’t your father tell you this was no place for a little girl? Had you listened to him, you would still be home, warm and safe!

Minka jammed her hands under her arms and felt moisture freezing to her cheeks.

This isn’t what you want to do, little girl. The North Wind chortled and the fir trees, their needles chattering, seemed to laugh with it. You’re a child, and children know little. Look for your precious comet, and weep. Weep, and remember that your vanity and silliness brought you to this low place!

Minka studied the clouded sky, blinking back tears, then swiped her cheeks with the back of her hand. She exhaled quietly. “No.”

The air stilled, like a held breath. Minka looked up to the plateau, and shook her head.

“No!” she said again, louder this time. “I won’t weep. Why should I? I came looking for an undiscovered comet. That’s not silly, it’s what astronomers do. We look for the new and undiscovered things. Maybe I won’t get to see it tonight, but there will be others.” She steadied the telescope and sat on the rock next to it. “I will not weep, North Wind, because I’m glad I’m here. I am an astronomer, cold nights and danger and all.”

The North Wind roared, and Minka’s teeth chattered. She clenched her jaw and tucked her chin into the tatters of her scarf.

Then, in the trees, she heard the jangle of bells, and the rush of wood runners over snow. A reindeer, silver-ruffed and velvet-antlered, trotted into the clearing, pulling a wooden sleigh behind it. It came to a halt and its rider stepped off, pushing a fur-lined hood back to reveal a woman, her cheeks ruddy with cold. She gazed at Minka for a moment, then lifted her dark eyes to the sky, where the clouds were whipped into a froth by the wind.

“Knock it off!” she shouted.

The North Wind stuttered with a discordant huff, and fell silent. The woman nodded and marched up to Minka, then bent over to study the torn bag. Minka gaped at her.

“Who are you?”

The woman straightened, bag in arms. “I am the North Wind’s sister,” she said. “You are the stargazer, aren’t you?”

Minka nodded and the woman’s face crinkled into a smile. She set the bag down on the sleigh and covered it with a thick, brown pelt—moose, perhaps, or bear.

“I came to rescue you from my capricious brother,” she said over her shoulder as she worked. “But you seem to have things well in hand. I’m impressed. So is he.”

Minka snorted and gripped her father’s telescope tighter. “I didn’t come out here to impress either of you. I came out to see a comet.”

“So you did.” The woman turned to face Minka, and her eyes sparkled like stars themselves. “Look up, then, and see what your tenacity brought you.”

As Minka watched, the woman looked up and blew a cloud of breath with a soft whistling noise. The branches shivered and a mild breeze tickled the hair on the back of Minka’s neck. She looked up and gasped—the clouds coiled and pushed against each other, breaking up so patches of sky showed through. The North Wind’s sister blew again, and the clouds rolled away, revealing stars as far as Minka could see. She peered through the telescope’s eyepiece, and saw the same magnificent stars, illuminated and magnified. And in the center of her telescope’s view, she spied a blip only a bit brighter than the rest, its color a little different, its light a little strange. Minka fumbled with the telescope, focusing on that bright point, squinting to see its form more clearly. What does it look like up close, she wondered? Visions of a blazing star flickered through her imagination, its long tail cutting an arc through the sky, and her cheeks ached with her widening smile.

“That’s it! Oh, I bet that’s it!” She waved one hand at the North Wind’s sister, the other cupped around that blurred light smudge. “Could you bring me some dry paper? And a pencil?”

One of her father’s notebooks appeared in her line of vision, a pencil tucked into its folds. A pair of fur mittens and her missing hat followed them. The North Wind’s sister saluted her, then sat in the snow and leaned back to look up at the sky. The whole clearing gleamed.

Minka unfolded the notebook to a blank spread. She stuffed her hands into the mittens, breathless with excitement, bowed her head, and got to work.

The North Wind’s sister accompanied her home, several hours later. Minka lugged her father’s bag through the front door, only to be pulled off her feet by the astronomer and spun around.

“My girl!” He wept with relief. “My beloved girl!”

He ushered them into the kitchen and fed them slices of birthday cake. “Never do that again,” he said. “You could have been killed!”

“But I wasn’t,” Minka said. “I told you, this is what I want to do. And look what I found.” She pushed her sketches and notes across the table and waited while he read them. At last, he looked up at her, eyes wide.

“This is excellent,” he said. “Truly, it is. I’ll need to watch it a while longer to ensure—”

“We,” Minka said.

The astronomer paused, then nodded. “Yes. We. We will need to go out and monitor its progress.”

Next to her father, the North Wind’s sister winked at Minka.

They named Minka’s discovery the North Wind comet. She and her father went out every night, charting its trajectory until it passed out of sight, then documenting other phenomena, together. And no one ever again suggested Minka wouldn’t be an astronomer.

Order the Ebook Today

Kindle US | Kindle UK | B&N | Google Play | Kobo | Smashwords

Coming Soon

iBooks

Buy from The Book Smugglers:

DRM-Free ePub, Mobi

Add the book on Goodreads: HERE.

3 Comments

Paul Weimer

December 2, 2014 at 6:14 amA sweet and well written story!

Catherine King

December 3, 2014 at 2:13 amThat was a beautiful story! Even though it was brief I got a clear sense of Minka’s character, and the wily wild North Wind. And the descriptions of the cold and stones on the mountain were so sharp I almost felt them myself.

Your Emergency Holographic 2015 Hugo Short Fiction Reading List | File 770

March 8, 2015 at 7:35 pm[…] The Astronomer Who Met The North Wind by Kate Hall ( * ) […]