SFF in Conversation is a new monthly feature on The Book Smugglers in which we invite guests to talk about a variety of topics important to speculative fiction fans, authors, and readers. Our vision is to create a safe (moderated) space for thoughtful conversation about the genre, with a special focus on inclusivity and diversity in SFF. Anyone can participate and we are welcoming emailed topic submissions from authors, bloggers, readers, and fans of all categories, age ranges, and subgenres beneath the speculative fiction umbrella.

Today, we are pleased and proud to host a diverse mythical creatures round table with an amazing group of authors: Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Shveta Thakrar, Octavia Cade, Marie Brennan, Whiti Hereaka, Rochita Loenen-Ruiz, E.C. Myers, Aliette de Bodard, Benjanun Sriduangkaew, Bogi Takács and Joyce Chng.

We will open the proceedings with an introduction from Shveta Thakrar, responsible for the prompt that originated the round table:

I’ve always loved faeries, always, always, but ever since I looked around one day in my early twenties and realized that was pretty much all I knew about, I’ve been hunting stories using folklore and mythical creatures from around the world. Until then, it never occurred to me to wonder why I didn’t see the nagas and apsaras from my own South Asian heritage in any media outside Amar Chitra Katha, the comics I’d read as a kid. At best, they might show up in the cloth painting or statuary a Hindu household tended to have, but beyond that, they might as well not exist. And once I realized that, I got angry–and started writing my own tales and thinking about what else I could do?

So when I saw Strange Horizons posted a column on types of fey beings, I mentioned on Twitter that I would love to see a global version that would introduce people to creatures they might not have heard of. Ana of the Book Smugglers saw my tweet and approached me about hosting a round table on her website. Of course, I jumped at the opportunity!

I still love faeries, but now I want more. I want to see the mythical beings that exist outside Celtic and British lore, too, and want to see them star in stories that everyone knows, no matter where they grew up. I want it to be common knowledge that J. K. Rowling did not invent naginis, and I want our fantasy novels and movies to encompass the true richness of global lore and myth. (When I say myth, it’s referring to the original meaning of “sacred story” as opposed to “lie.”) Highlighting one branch of folklore at the expense of most of the rest is othering and dismissive, but even more than that, it’s cheating ourselves of the rest of the beauty and wisdom out there. Folklore, whether or not you believe in its creatures, exists to show us other ways to be and to remind us to stay open to wonder and magic. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I am starving for all the flavors of magic I can find, so as far as I’m concerned, bring on the world treasure trove of stories!

And now, without further ado here is part 1 of the round table, featuring the contributions by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Shveta Thakrar, Octavia Cade, Marie Brennan, Whiti Hereaka, Rochita Loenen-Ruiz.

Part two with E.C. Myers, Aliette de Bodard, Benjanun Sriduangkaew, Bogi Takács and Joyce Chng can be found here.

SILVIA MORENO-GARCIA

Mexican by birth, Canadian by inclination. Silvia lives in beautiful British Columbia with her family and two cats. She writes speculative fiction (from magic realism to horror). Her short stories have appeared in places such as The Book of Cthulhu and Imaginarium 2012: The Best Canadian Speculative Writing. Her first collection, This Strange Way of Dying, was released in 2013. Her debut novel, Signal to Noise, will be released in 2015 by Solaris.

A nahual is a shape-shifting witch or warlock. Many creatures in Latin American folklore shed their skin and can transform. The nahual can transform into any kind of creature, though generally it will be a turkey, owl, dog or coyote. It is always malicious, ranging from small things such as killing cattle to making people ill with its spells.

The name nahual derives from the Nahuatl word nahualli, and in Aztec mythology it was the animal double of a person, determined by the day you were born. These beliefs probably merged with European myths to create the modern nahual, which has a negative connotation the nahualli did not have.

When my great-grandmother told me stories about nahuales she would start by saying “there are animals that are not animals…” and proceed with her tale.

I’ve seen chaneques called Aztec fairies or goblins, which I think is a wrong interpretation and also reduces the intense disquiet I feel about these creatures. They are described in different ways, frequently as children with the face of old men or women, who hide objects and play pranks. They also kidnap travellers that venture into the forest, jungle or hills, and can cause disease. They are strongly associated with the natural world. My great-grandmother used to tell me a very frightening tale about a specific chaneque who devoured a child.

La Llorona is probably the most popular Mexican legend outside of Mexico. Literally, “The Weeping Woman,” she is a spectre that spends her nights wandering around, screaming for her children. She is associated with bodies of water, like rivers or lakes, though more modern takes have her haunting highways. The story goes that the Llorona was a beautiful indigenous woman who married a Spaniard and had children with him. He then dumped her and in a fit of fury she drowned her children. The story has tones of Medea, but also is connected to Mexican history. It is supposed to symbolize the clash of European and native cultures. In a way, the Llorona can be interpreted to be crying over all her children, the Mexicans who emerged from that fusion of cultures.

Though La Llorona is generally portrayed as having a connection with water, the story about La Llorona I heard from my great-uncle was that he met her one day while riding across a rather arid area.

The tlahuelpuchi has been called a Mexican vampire and I suppose it qualifies as one, since it drinks the blood of people. However, it is more of a witch-vampire, which is quite normal: a lot of witches in Latin American folklore drink the blood of people or eat babies. The tlahuelpuchi can transform into a turkey. It makes its way, loosely interpreted, as a vampire in modern-day Mexico City in my second novel Young Blood.

I’d like to make one final point now. My folklore came via by great-grandmother, who was a peasant and grew up in the country-side around the time of the Mexican Revolution. Her view of the world colours my writing. It is, however, not the typical education I think most Mexicans have. I doubt very many city-folk nowadays talk or even know about things such as nahuales or chaneques. My husband, who was born and raised in Mexico City, for example, is often surprised when I talk about certain creatures and superstitions. My knowledge is of another time and place, one that I think is ceasing to exist even in rural areas, for a variety of reasons which include the popularization of ‘foreign’ myths, legends and stories.

SHVETA THAKRAR

Shveta Thakrar is a writer of South Asian–flavored fantasy, social justice activist, and part-time nagini. She draws on her heritage, her experience growing up with two cultures, and her love of myth to spin stories about spider silk and shadows, magic and marauders, and courageous girls illuminated by dancing rainbow flames. When not hard at work on her second novel, a young adult fantasy about stars, Shveta makes things out of glitter and paper and felt, devours books, daydreams, bakes sweet treats, travels, and occasionally even practices her harp.

Apsaras are extremely beautiful, sensual female spirits associated with clouds and water in Hindu and Buddhist lore. Skilled dancers and singers, they often perform to the music of their gandharva consorts at King Indra’s and Queen Indrani’s court in the heavenly realm of Svargalok.

There are two types of apsaras: earthly and divine. All renowned temptresses, they are often tasked by Lord Indra with trying to tempt ascetics away from their practice. When Siddhartha Gautama was sitting beneath the bodhi tree on the brink of achieving enlightenment, a group of apsaras was dispatched to distract him with their feminine wiles. (Such was his devotion to his goal, he resisted.)

Apsaras can change their shape at will, often taking the form of waterfowl. Creatures of the moment, they make fleeting lovers and tend to abandon any children that come from these unions. It is not surprising, then, that apsaras are thought to preside over the outcomes of games of chance and gambling.

Famous apsaras from literature include Urvashi and Tilottama. Urvashi fell in love with the human king Pururavas and won him away from his human wife. During an argument, she wanders into forbidden territory and is temporarily turned into a vine before Pururavas finally finds her again.

Meanwhile, Tilottama was created by the divine architect Vishwakarma to deal with two demons who had won boons protecting them from everyone but each other. Made from all the best ingredients in all the three worlds, she was so lovely that the brothers fought over her and ultimately committed mutual fraticide. Even some of the gods themselves are said to be smitten with her.

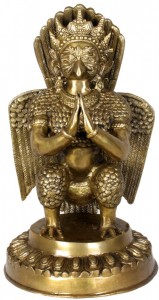

Garudas (feminine form garudi) are eagle people, born of the creator-sage Kashyapa and his wife Vinata. The first garuda hatched from an egg in a fire so great, it scared even the gods.

Garudas are depicted as having the golden body of a strong man, a white face, red wings, an eagle’s beak, and a crown, though they can also shift shape in order to hide among humans. They have wingspans of many miles with plumage thick enough to hide a man.

Cousins of the nagas, they bear their serpentine kin an eternal grudge and seek to devour them whenever possible.

This grudge is the result of a foolish wager made between Garuda’s mother Vinata and her sister Kadru, mother of the nagas; When Vinata lost, she became enslaved to Kadru. Horrified, Garuda approached the nagas and asked what price his mother’s freedom might fetch. The nagas would settle for nothing less than the amrit of immortality, which was safely ensconced in the heavenly realm of Svargalok. Garuda went to Svargalok, where he fought off the devas (demigods) and defeated all their protective mechanisms. Then he took the elixir into his mouth. On his way down, he encountered Lord Vishnu, who promised him immortality and agreed to let him take the amrit as long as he did not swallow it, and in return, Garuda agreed to serve as his mount. Then Garuda came across Lord Indra and promised that once the amrit had been delivered to the nagas, he would find a way to return it to Svargalok. In return, Lord Indra granted him free passage and offered to let him have the nagas as food.

When Garuda deposited the amrit on the grass near the nagas, he urged them to cleanse themselves via ritual before partaking of the amrit. While they were occupied doing so, Lord Indra appeared and reclaimed the amrit.

Garuda

Nagas (feminine form nagi or nagini) are shape-shifting serpent people, born of creator-sage Kashyapa and his wife Kadru. Some nagas dwell in the heavenly realm of Svargalok, while others reside in a subterranean kingdom. They are depicted as having human faces and torsos (sometimes with a snake hood) and a long, serpentine coil from the waist down and are thought to be fond of gold and jewels.

Cousins of the garudas, nagas bear their avian cousins an eternal grudge and avoid them as much as possible in order to avoid becoming dinner. But Garuda’s revenge for their mistreatment of his mother was not complete; though he tricked them out of drinking the amrit of immortality, a few drops fell to the grass when Lord Indra came to retrieve it. As the nagas thirstily licked up those droplets, the sharp grass blades sliced their tongues, giving them forked ones, and they received the power of regeneration—the molting of old skins in favor of new ones.

Examples of famous nagas include Sheshanaga and Uloopi. Shesha is the king of all nagas and one of the primal beings of creation. He has a thousand heads and floats in the cosmic Ocean of Milk, serving as a lounge for Lord Vishnu. Disgusted by the cruel actions of many of his brethren, he left his family and chose to practice severe penance for Lord Brahma. Pleased with the naga’s devotion, Brahma sent Shesha to the netherworld to support the unstable earth with his hood, where he remains even today.

Uloopi is a nagini princess from the subterranean kingdom, and one morning when Prince Arjun went to take his bath in a river, she caused him to fall down to her land. There she confessed her love for him and begged him to marry her. Charmed by her adoration, Arjun agreed to stay with her for one year as her husband. At the end of the year, he returned to the surface world and married a human princess, Chitrangada, who bore him a son, Bhubhruvahan. Uloopi learned of Bhubhruvahan and helped raise him as her own. Later, Arjun was cursed to be killed by his own son in battle. Knowing she can bring Arjun back, Uloopi convinced Bhubhruvahan to commit the slaughter and thus fulfill the curse. Once Arjuna lay dead, Uloopi revealed and employed a powerful gem belonging to the nagas, Mritasanjivini, to restore a now curse-free Arjun to life.

OCTAVIA CADE

Octavia Cade has had short stories published in Strange Horizons, Aurealis, and The Dark amongst other places. Her first book, “Trading Rosemary”, was published this year and an urban fantasy novella, “The Don’t Girls”, is due out in October. She has a degree in botany, and still kind of hopes that the trees will win.

Some years back I spent a summer in Denmark, picking strawberries. This was about as far away from New Zealand as I could get. It was also the year that LOTR: The Two Towers came out. I went to see it eleven times. Now I could tell you that I went because the Danish landscape, pretty though it may have been, was pikelet-flat and I was sick for the sight of mountains, and that would be true. It wouldn’t be the whole truth. I also went for the Ents. There was a deep, visceral pleasure in seeing trees beat hell out of those orc industrialists, the smash and crash of branches.

But here’s the thing: fond as I am of Tolkien, and as interesting as I find the tree mythology that permeates his work, there comes a time when the Edda and all its derivatives take a back seat. When I think of the world tree, it’s not an ash I think of. It’s a kauri – that giant of the New Zealand bush, so very far from Denmark. Tolkien wouldn’t have known one if he’d tripped over it.

That’s the thing about tree mythology, about the creatures and structures we conjure up. In many ways it’s a local thing. Most people on Earth – not all, but most – live in regions where trees are a common thing. Not any old tree either, but different species, representing different biomes, different ecologies. Different uses. Local trees, shaping local stories. In Northern Europe the sky is held up by an ash or a yew. In Australia, it’s a gum tree or a casuarina. We use what we have, what we see in front of us every day.

Most cultures have some version of the world tree – a cosmically significant, even structural object. Yggdrasil is a common example of this, but one of the younger and far from the only one. Think, for instance, of the kiskana tree of Babylonian myth, with its appearance of lapis-lazuli. It’s a short step from a world tree to a wise tree. Myth and legend around the world abounds with examples of trees of knowledge. You can understand why it happens. Age tends to be associated with experience, and when a community spends generations living with something so much older than they are – bristlecone pines can live for thousands of years, as can kauri, cypress, and a number of other species – it’s no wonder that connotations begin to spread.

But knowledge is useless if it can’t be communicated. Hence, there are a number of trees of knowledge that can do just that – that can talk and reason and even foretell the future. An example from down the Pacific way is the Fijian Tree of Speech, Akau-lea. This tree would direct the kava bowl, instructing the gods gathered beneath who would be next to drink. It also gave warnings, as it did to Maui, though as is the nature of warnings these were not always listened to and disaster inevitably followed.

One can of course take this idea of a literal tree-creature and expand it to the idea of the associated creature – a dryad-type of woodland creature that resides with the tree, linked to it. The tree and the creature are essentially symbiotic, a living pair. Offhand I can think of a great heaping pile of fantasy books that take advantage of this aspect of mythology. There exists a flip side to this associated relationship, though, one where the connection is death instead of life. Consider the relationship between the ghostly women who make their home in banana trees (Nang Tani of Thai folklore, for instance, or the predatory Pontianak of Malaysian mythology). Or how in the Pacific Islands, for instance, trees (pohutukawa, breadfruit, coconut…) are often related to the afterlife, and used as a sort of jumping off point for the spirits of the dead, who crawl along branches and roots. In the Gilbert Islands, this is taken even further, with a myth of men and women mixing it up when they shouldn’t under the tree of death and thus becoming mortal.

You’ll note a lot of my examples are Pacific based. I can’t help it – these are the stories of my doorstep, even if my ancestors came from another place entirely. They’re not my stories, but I can’t close my eyes and pretend not to see them, pretend they don’t inform the local world in which I live. That’s a pohutukawa up at Cape Reinga, the leaping place of spirits, not a bloody yew. Both are associated with death, in their ways, and those ways are not the same. Looking the other way so as to have an excuse not to deal with the (admittedly significant) problem of appropriation isn’t, I think, helpful.

I’m about to get off mythology here, I know, but I’d like to offer an opinion. If we want to diversify speculative fiction then we need to see where stories come from, the stories of other cultures – and one of those places is biology, the extraordinary diversity of the natural world. If you’re looking for diversity, you can’t go past the trees. Biological diversity goes hand in root with that of culture, and tempting as it is to stick with the same old standbys – oak and ash and the willows that walk behind at night – consider that truth can be as strange as fiction, and walks behind as closely. Tolkien made up his Ents from whole cloth, and they might be fantasy tree creatures par excellence, but if the Central American manchineel could walk it’d give them a run for their money. The damn things are so toxic they come with their own warnings signs. Try to kill one with fire and the smoke will blind you. That’s a tree that doesn’t need to touch you to hurt you: a true stationary horror. Or there’s the Gympie-Gympie stinging tree (alright, it’s technically a shrub) from Queensland, proof positive that in Australia, even the vegetation’s out to get you. Capable of killing a horse, the sting of this green beast has been described as a cross between an acid burn and an electric shock. The pain experienced from walking into one unawares has been known to last for years. When this is what’s outside your door, it’s going to have an effect on your stories – from myth to fantasy and back.

MARIE BRENNAN

Marie Brennan is a former academic with a background in archaeology, anthropology, and folklore, which she now puts to rather cockeyed use in writing fantasy. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she spends her time practicing piano, studying karate, and playing a variety of role-playing games.

What’s in a name? A dragon by any other name would be as dangerous . . .

Or would it?

“Dragon” is one of those terms that’s both specific and generic — kind of like “Kleenex” or “Band-Aid.” Your standard dragon, the name-brand variety, is reptilian, four-legged and winged, probably breathes fire, is almost certainly fond of treasure. But there’s a whole range of stuff from around the world that gets grouped under that name . . . and it’s easy to forget their differences in pursuit of their similarities.

Take the Quetzalcoatl, for example. Capitalized, it’s an Aztec god; the name means “feathered serpent.” Lowercase, it’s a creature often seen in Mesoamerican art. (The Mayan equivalents are Kukulkan or Q’uq’umatz.) It often gets lumped in with European dragons as their Central American cousin. But what do they have in common? When you get down to it, the answer is “not a lot.” As the name suggests, a quetzalcoatl has feathers instead of scales, and the historical depictions — as opposed to the modern ones you find in texts like Dungeons and Dragons — don’t generally have legs and wings. They don’t breathe fire. In fact, they have more of an elemental connection with wind and clouds.

In that respect, they’re much more like Asian dragons than the European kind. And maybe that’s the key to the answer: Europe had large, magical snake-type creatures in its folklore, and so did East Asia, which made people decide that “dragon” was a universal concept — whereupon they started looking for dragons all over the world. Any sort of creature fitting the general concept gets the label.

There’s merit to that kind of approach. Sometimes noting the commonalities between different things helps us understand things about the world, whether those commonalities have their roots in cultural borrowing or simply the same impulse giving rise to the same ideas. But for storytellers especially, it’s important not to lose sight of the trees for the forest.

Because those differences? Those are where the story lives. Writers are often told to be specific; well, that applies to concepts as much as to the words that go on the page. A medieval European dragon has symbolic connections to snakes, ergo to the serpent in the Garden of Eden, ergo to Satan and other evil things. But a quetzalcoatl’s connections are to one of the most important gods in the Aztec pantheon, a patron of the priesthood and civilization. If you go a little way down the research rabbit-hole, you find echoes of fertility and vegetation, a link to the planet Venus — and if you’re researching Mesoamerican stuff more broadly, instead of just cherry-picking out one creature, you find that the sacred 260-day calendar (tzolkin to the Maya; tonalpohualli to the Aztecs) may have had its origins in the astronomical cycle of Venus. Interesting, isn’t it? If you treat a quetzalcoatl like a dragon with feathers, you’ll get one kind of story: a standard piece of Eurofantasy with a Mesoamerican paint job. But if you pay attention to the context, you’ll tell something much different, much more vivid — and much more respectful.

I’ve focused on this example because it’s one I know reasonably well. The same applies, though, to other dragon-type creatures around the world: the Rainbow Serpent of Aboriginal Australia, the naga of South and Southeast Asia, the multiplicity of dragons found in China, Korea, and Japan. Their similarities to European dragons might be a reason to look at them — but once there, look for the differences, and think about what they mean. What happens when your serpentine creature lives in a river instead of a cave? What changes when the creature is a god, or worships the same gods human beings do, or is sacrificed by humans to those gods? What are the stories told about these creatures in their home cultures, and how does the shape of those stories differ from the standard shapes we see in Western-style tales?

Writing about them presents its own challenges, of course: the balancing act between fidelity to the source material and adaptation to the standards of modern fiction. And to be honest, folklore isn’t as consistent as we like to think; one primary source may contradict the next. But that doesn’t mean research isn’t worth the effort. Without knowledge of those differences, we’ll just end up telling the same stories.

WHITI HEREAKA

Whiti Hereaka is an award winning playwright and novelist. She is the author of The Graphologist’s Apprentice and Bugs (available from: http://www.huia.co.nz/). She is currently working on a novel about the life, death and life of Kurangaituku, the bird-woman.

The supernatural creatures of traditional Maori stories have not really been used as character “types”. If a supernatural being appears in a story it is usually has its own name and history. Also, they are often associated with a specific area or people (iwi or tribe), so it would be unusual for an outsider to appropriate that creature.

The supernatural creature most New Zealanders are familiar with are Taniwha. “Taniwha” is usually translated to “monster”. Although this translation is a little simplistic: a formidable (rather than monstrous) person can be described as a “taniwha”.

Taniwha have been described as water “dragons” as they mostly live near or in water. Often taniwha are described as gigantic lizards; but many taniwha can take on whatever form they wish. The man-eating taniwha Hotupuku, who preyed on travellers making the journey through the Kaingaroa forest between Rotorua and Taupo, has been described as being at once like a tuatara and a huhu grub and was the size of a sperm whale.

Horomatangi, the taniwha who lives in the lake of my hometown Taupo, is known to take the shape of a lizard and as a black rock when he is observed in the lake. He lives in an underwater cave off the small island in the middle of Lake Taupo – Motutaiko. Near Horomatangi’s home is a reef (also named after him) that is treacherous to those who cross the lake. Those who dared to cross over the reef risk the wrath of Horomatangi; who would trap waka (canoes) in a whirlpool, capsize the vessel and devour all aboard. The journey could be made safe if a person with sufficient mana (prestige, power, charisma, pride) was on board and they managed to mollify Horomatangi.

Some taniwha, Horomatangi included, act as guardians for the local iwi; but even if the taniwha is your guardian, they must be treated with caution. In one story about Horomatangi and his cousin Hurukareao, a local woman who was insulted by an iwi near Rotorua, called upon the two taniwha to restore her mana. Her incantations roused the taniwha so much that they did great damage to her own village before they set off to lay waste to the people that had insulted her.

Horomatangi is credited with the creation of some of the natural phenomena in the Taupo region. On his journey from White Island to Taupo to assist Kuiwai’s search for her brother the tohunga (expert or priest) Ngatoroirangi, Horomatangi’s exhalation created the Karapiti blowhole at Wairakei. Other taniwha have helped shaped New Zealand as well – the battle between two taniwha shaped the harbour in our capital city, Wellington.

As a child, whenever my family travelled north we’d stop at Hatupatu’s rock to leave a koha (gift) for a safe journey. This was the very rock that had sheltered the hero Hatupatu from the terrifying bird-woman, Kurangaituku. At the front of the rock is the opening that Hatupatu created with an incantation and that he crouched in while Kurangaituku’s claws gouged the rest of the rock.

Hatupatu’s rock appears near the end of the story of his encounter with Kurangaituku. It is the kind of story that is told in the dark of night; a brave young hero who faces the wrath of an ogress or witch.

Kurangaituku (or “Kura of the Claws”) has the head of a bird – her lips are pulled into a long, sharp beak. She has wings are attached to the underside of her arms. She has long fingernails or claws at her fingertips. In the pictures of her I remember from my childhood, she is flat chested – almost mannish; but this could be because the publishers were a little shy of female nudity in a picture book! In that story it is said that when Kurangaituku found Hatupatu in the forest she took him home as a mokai (pet); in other versions it is said she takes him home as a husband. I favour the latter telling – in old stories fingernails are sometimes used as a motif for sexuality; so it makes sense that “Kura of the Claws” would take a husband rather than a pet. Also the story of Hatupatu is a classic hero’s journey, his coming of age, so I doubt the original storytellers would have shied away from the sexual inference.

Kurangaituku is capable of travelling vast distances quickly – helped by her wings and an incantation she recites.

Her home is a cave filled with wonders. Kurangaituku has amassed a collection of birds and lizards that act like her familiars – they watch Hatupatu while Kurangaituku is away hunting. She also has a collection of taonga (treasure): fine, feathered cloaks and weapons that Hatupatu covets.

Hatupatu stays with Kurangaituku for a while. She shares her food with him (raw birds, which he pretends to eat and then cooks while Kurangaituku is away hunting) and her home.

One day, Hatupatu convinces Kurangaituku that the best hunting grounds are far away at the foot of a mountain range. As soon as she sets off, Hatupatu kills her familiars and takes the taonga. He misses a small bird, who flies to Kurangaituku to tell of Hatupatu’s betrayal.

Kurangaituku races back to her home to see the destruction. Enraged she chases after Hatupatu, who takes shelter in a rock. He emerges from the rock thinking the coast is clear; but Kurangaituku pursues him again.

Near Hatupatu’s home is a boiling mud pool called Te Hemo. In the story Hatupatu jumps over the pool, but Kurangaituku being a stranger wades through it. She dies in the boiling mud and Hatupatu returns home with her fine, feather cloaks and weapons to become a celebrated hero.

ROCHITA LOENEN-RUIZ

Rochita Loenen-Ruiz is a Filipina writer living in the Netherlands. She attended the Clarion West Writer’s Workshop in 2009 and was a recipient of the Octavia Butler Scholarship. Her work has been published in various online and print publications in the Philippines as well as outside of the Philippines.

Shapeshifters, flesh-eaters, beings who capture and take away children and humans at will—no matter what culture or place magical and horrific creatures seem to be part of the tapestry of storytelling.

Probably the most well-known of all Filipino monsters is the being called Aswang. Most popularly depicted as a being who takes on the visage of a beautiful woman who lures in her prey only to consume them later, the aswang has many different manifestations and functions as a sort of blanket term for all these different forms.

The most popular form of aswang is of a woman who divides in half at a certain time of month. From being a beautiful woman, she takes on the form of a hag, grows wings and leaves her lower half in a secret place while she goes off to hunt. Her preferred prey being the innocent and untried youth as the flesh of virgins is said to be more succulent than the flesh of older and more experienced prey.

Another form that the aswang takes is that of a shapeshifter. It is said that this kind of aswang will take on the shape of a huge black dog or a gigantic wild boar who then goes off in search of a victim.

In the Visayan region, the aswang may sometimes take on the appearance of a good-looking male. This particular kind has a familiar who is called the tiktik. Deriving its name from the sound that it makes, the tiktik is the creature most feared by pregnant women.

Pregnant women are often advised never to sleep on their backs as this leaves their bellies exposed. The tiktik is depicted as a large black bird with a sharp yellow beak. When the time is right, it flies to the home of marked prey.

With its sharp beak, it proceeds to drill a hole in the ceiling. Through the hole, it lets down its long sharp tongue which passes painlessly through the woman’s bellybutton. Through its tongue, the tiktik proceeds to suck up the fetus.

From the stories I heard when I was a child, the tiktik’s consumption of the fetus also serves to re-energize its master, the aswang. It seems that a symbiotic relationship exists between the two and when the familiar dies, the master perishes as well.

There are various means of warding off these aswang manifestations. The most popular being to hang garlands of garlic at major entry points to your house. Something about the smell of garlic disgusts these creatures.

Throwing holy water on aswang is said to melt them and kill them. A method that is particular to the kind that divides in half is to find the lower body and sprinkle sea salt into the lower half. It is said that when the aswang returns from her hunt, she becomes unable to rejoin with her lower half as the sea salt stings and corrodes the flesh. An aswang who is unable to rejoin with her lower half perishes when the sun rises.

There are other horrific creatures in Philippine myth, but of all these creatures, the aswang has been one that has been most depicted in films. Whether the fascination has to do with the various forms it takes, with the danger or temptation it represents, one can only guess.

One of the creatures that I used to find both horrific as well as fascinating was the tikbalang. It’s interesting to note that there are also a number of variations in the stories told about this creature. The tikbalang is another of those creatures that is capable of shifting shape at will, but its most popular form is that of a gigantic creature with long bony arms and legs with a horse-like countenance. Some versions of the tikbalang have him taking away children while other versions depict him as a harmless creature who is simply terrifying to look at.

Whichever version you hear, depends on who does the telling and to whom it is told. The version I heard as a child was one where the tikbalang would come to get me if I didn’t go to bed on time. I now suspect that this story was simply told to get children into bed with as little fuss as possible.

There are more magical and horrific creatures in Philippine mythology. Some simply exist to hunt and eat prey, while others exist as a form of romance.

It’s said that the tiyanak is a manifestation of aborted babies. It often manifests as an infant and appears in bushy or jungle areas.

The tiyanak lures in its prey by its cries. Passersby often assume that this baby is an abandoned child. It is when they pick up the baby that it transforms into a tiyanak who then proceeds to kill and consume its prey.

There are also stories that go around about how the tiyanak disorient their victims and cause them to lose their way. Children are a particular favorite for this particular trick.

Peque Gallaga, a multi-awarded film director from the Philippines, has made a number of movies around some of Philippines’ most famous (notorious) monsters. Unfortunately, the version of the film I saw which featured the tiyanak, made it clear that the tiyanak was made out of plastic. Something which somehow robbed the film of the scary effect. Perhaps this has been rectified in later film versions.

I still am undecided as to whether the enkantos are romantic or horrific. Stories that circulate around these beings feel more like a horror romance rather than pure romance.

Enkantos are said to occupy places that are rarely visited by humans. They are said to be invisible to the human eyes except to the men or women who they become enamored with.

A friend told me a story of an enkantos courtship of her great grandmother. Her great grandmother encountered this being when she was already married and had children. The enkanto courted her and asked her to join him in his kingdom but she refused him. Regardless of her refusal, the enkanto continued to come and visit her at her home. Sometimes alone, sometimes accompanied by an entourage.

According to this story, the woman would point them out to her family declaring their presence in the home before she would fall into a trancelike state.

The head of the family who happened to be a seer was able to corroborate these visits and through his efforts, the enkanto were eventually driven away.

Another version of the story has it that the enkanto were never driven away but they simply waited for the day when she was liberated from her body.

The tales around the enkanto range from kidnappings of the desired prey. They rarely end in violence, but they often involve unexplained disappearances, trances and physical seizures.

Horrific or romantic, I leave it up to the reader to decide.

FURTHER READING:

7 Comments

Paul Weimer

September 23, 2014 at 6:05 amOh, this is wonderful. I’ve heard of some of these (Nagas are, um, in the D&D Monster Manual) but many of these are extremely new to me.

Shveta Thakrar

September 23, 2014 at 10:51 amPaul, yes, a horribly distorted version of nagas can be found in D&D, which really upset me when I saw it. That’s not what nagas are, and why we have to be careful when we take things from other people’s cultures/religions.

Annamal

September 23, 2014 at 8:19 pmThis is awesome, thank you.

One Maori supernatural character “type” that I think has been used successfully are the Patupaiarehe.

Kim Aippersbach

September 24, 2014 at 12:04 amWhat a great idea for a roundtable discussion and what a great bunch of contributors! I have never heard of most of those supernatural entities, and I would love to read stories and novels about them. European fairies have been done—maybe not ad nauseum, but ad infinitum for sure.

I love the stories told by peoples’ grandmothers, and I think those are the people who need to write the novels, because they know that frisson of fear that the monsters are real, and they know the ins and outs of how to placate them.

Cindy

September 24, 2014 at 6:24 amSuch a great initiative! I love reading and knowing more about mythical creatures and I found it a pity when you always read about the same creatures with few variations. Thank you Book Smugglers ladies and the authors for this post, I’m looking forward to the second part!

Kristy

September 29, 2014 at 12:33 pmI love this round table! I love mythological creatures and I go out of my way to find new/unusual/rarely used creatures in my own writing. This round table is fertile character/story ground! There are two books I use quite heavily in my own writing that might be of interest to the folks in this thread. The Dictionary of Mythology is an enormous tome filled to the brim with mythology. The other is A Witch’s Guide to Faery Folk by Edain McCoy and it has an incredibly diverse array of beings from all around the world. Far from complete of course, but an excellent resource all the same.

Signalboosts & Links • Little Lion Lynnet's

August 4, 2015 at 4:31 am[…] have started up a round table about diverse mythical creatures. You can read the first part here and the second part […]