Welcome to Halloween Week 2015! Over the course of the week, you will hear from guest authors, bloggers, and your very own Book Smugglers about all things Halloween–including reviews of horror novels and films, essays on the genre, and any number of spooky topics in between.

Continuing with this year’s Halloween Week, we have guest author Michal Wojcik to talk about Horror writer Stefan Grabiński.

![]()

Inner Demons in Motion:

The Horror of Stefan Grabiński

I like my horror slow and subtle, prefer a long atmospheric build instead of a visceral gut-punch. Start with a queasy feeling in the pit of my stomach that increases in increments over the course of the story and then stays with me long, long after; absorb the unsettling and the uncomfortable and then let it stew in my brain. That’s the ticket.

No other author affects me this way as much as Stefan Grabiński.

Grabiński was, for a long time, one of the forgotten horror writers of the early twentieth century, even in his native Poland. Born in 1887, he published a number of famous-at-the-time short story and novels while dying a slow death from tuberculosis, before succumbing in 1936 and falling into obscurity. Fortunately, he’s experiencing something of a renaissance at the moment, with several translations of his works released in English and reaching an international audience.

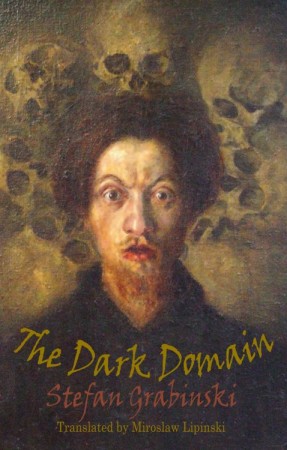

I first discovered Grabiński with the collection The Dark Domain (1993, edited and translated by Miroslaw Lipinski) while I was idly browsing the Polish literature section of the University of Alberta’s Rutherford Library in 2008. After tearing through the stories, I was entranced. And disturbed. Deeply and irrevocably disturbed.

The horrors of Grabiński are a horror of place, localized and personal, delving into the psychological issues of the protagonists with a relentless drive that’s warped and reflected by the space they inhabit. It’s a horror of isolation of a specific time, engaging with the clash of modernity with supernatural forces called forth by human progress. It’s a horror of human passions, desire, and deeply-experienced eroticism. The centrepieces (in my mind) of The Dark Domain display these features admirably: “Fumes” and “Szamota’s Mistress.”

“Fumes” is a hell of an introduction to Grabiński. A young engineer named Ozarski gets caught in a snowstorm, separated from his companions, and drags himself across the blank, snow-swept landscape until he stumbles across a ramshackle inn. There he’s cut off from the world, wandering the premises in the company of the innkeeper, his attractive young daughter, and a menacing old woman, none of whom Ozarski ever sees in the same room together. Their behaviour is just a tad bit off, but while Ozarski realizes there’s danger here, he also has feelings bubbling up that compel him to stay.

What follows is a night of transgressive sex (surprisingly frank and graphic for the time) and manifestations of the supernatural concentrating in his little room while the lamps burn low. As expected from the title, the experience of reading “Fumes” is very much like a hazy dream adhering to folkloric logic, never quite resolving into a recognizable reality.

That effect carries over to “Szamota’s Mistress”, where Szamota, a long-time admirer of a woman name Jadwiga, receives an unexpected invitation to her boudoir. Again, the action remains largely confined to a single room, this time with an image of Medusa watching the bed through nightly encounters with Jadwiga that become increasingly strange. Eventually, the situation resolves into body horror, but even that doesn’t quite stop Szamota from forging on.

For such small places, these locales themselves are important pieces in the atmospheric puzzle. Grabiński’s worlds are sparsely inhabited, with one or two significant characters, and claustrophobic, yet richly described. Every piece of the room in “Szamota’s Mistress” has some significance, innocuous on their own but together giving the sense that something is fundamentally wrong here; this little piece of geography has left the world that we know. Tight spaces and few (or any, as the case may be) other people gives sharp definition to the protagonists’ deepest thoughts and fears.

The walls truly crowd inward to a suffocating nearness with “In the Compartment”, which describes the bizarre psychological effects of a first-time train ride on the protagonist while he shares a compartment with a pair of newlyweds. That isn’t to say Grabiński’s stories are all like this, but I find the most effective ones are.

Discussions of early twentieth century horror writers often veer towards comparisons with H.P. Lovecraft—which seems especially silly here, given that Grabiński’s stories had no dialogue with Lovecraft’s in any practical sense, unlike much of the American horror canon. However, I’ll bring him up because I think Grabiński and Lovecraft reflect completely opposite approaches to the same interwar themes.

Lovecraft was revolted biological processes, manifesting in his personal life as queasiness around sex and manifesting in his fiction as slithering tentacles and squishy shoggoths. Sex, meanwhile, features prominently in Grabiński’s stories, not as a locus for revulsion but as a natural expression of desire that just happens to brush up against weird events. The focus is different: the main source for horror is not in vast alien beings but in the clean, impersonal steel of industrialization.

Trains feature prominently as agents of terror in Grabiński’s most lauded collection, The Motion Demon. The title gives a good sense of the horror Grabiński evokes: the increased pace of modern life awakening, or even creating, supernatural forces and beings that can manipulate us in terrible ways. The rational science that goes into technology produces irrational effects in the people who use it. Those effects are also decidedly divided from Lovecraft’s brand of “cosmic horror”: instead of an impersonal universe where beings outside human comprehension demonstrate our insignificance, the demons of motion remain inextricably bound to humanity; their evil is all too familiar and entirely knowable, and because of this are unstoppable.

In Grabiński, cosmic horror lives within us.

Nearly eighty years after Grabiński’s death, I still find this aspect of his work provocative. Grabiński frames the supernatural as outward and inward expressions of human hopes and fears as both outward and inward expressions of the same, and this gives his horror an inescapable quality. The further we try to escape the supernatural, the more malevolent it grows, the more it worms its way into our psyches and alters the world around us. And that’s scary, okay?

I’ve concentrated on The Dark Domain because for a long time it was the only collection of Grabiński’s stories available in English. More translations have since appeared, including The Motion Demon (2013), In Sarah’s House (2007) and On the Hill of Roses (2012). You can also read Grabiński’s short story “Strabismus” in The Weird Fiction Review for free.

![]()

Michal Wojcik was born in Poland, raised in the Yukon Territory, and educated in Edmonton and Montreal. He has a Master’s degree in history from McGill University, where he studied witchcraft trials in early modern Poland. His short fiction has appeared in On Spec: The Canadian Magazine of the Fantastic and Daily Science Fiction.

Michal Wojcik was born in Poland, raised in the Yukon Territory, and educated in Edmonton and Montreal. He has a Master’s degree in history from McGill University, where he studied witchcraft trials in early modern Poland. His short fiction has appeared in On Spec: The Canadian Magazine of the Fantastic and Daily Science Fiction.

Make sure to check his web serial: Zeppelins are What Dreams are Made of is a series of three steampunk-ish novellas featuring the dimension-hopping assassin Jennifer Asten.

Mrs Yaga, Michal Wojcik’s short story for The Book Smugglers is available now.

No Comments