SFF in Conversation is a monthly feature on The Book Smugglers in which we invite guests to talk about a variety of topics important to speculative fiction fans, authors, and readers. Our vision is to create a safe (moderated) space for thoughtful conversation about the genre, with a special focus on inclusivity and diversity in SFF. Anyone can participate and we are welcoming emailed topic submissions from authors, bloggers, readers, and fans of all categories, age ranges, and subgenres beneath the speculative fiction umbrella.

Today, we continue our ongoing new series “SFF in Conversation” with a guest post from Foz Meadows – YA author and 2013 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award nominee – on Fanfiction.

Thoughts on Fanfiction

by Foz Meadows

In the Beginning

The first book I ever wrote was a work of fanfiction.

Aged about five, I wrote a story about My Little Pony, illustrated it by tracing over pictures from my colouring book, then taped all the pages together to make an actual booklet. It was messy and childish and probably very sweet, and it was the most natural thing in the world for me to do, because this is how little kids play: by taking characters they know and like and transposing them into new narratives. Making up dialogue and adventures for my toy ponies during solo games involved an identical creative process to writing those same stories down, and if Starscream of the Decepticons sometimes joined in, too – well, why not? As films like the Toy Story franchise and, more recently, the Lego Movie are eager to point out, children don’t tend to compartmentalise their play. It doesn’t matter that Batman and Sailor Moon come from completely different franchises: if you have action figures of both to hand, then why not try and figure out which one would win in a fight? Toys are props in our earliest narrative engagements: they show us that it’s OK to cross the streams and create new things, to build pirate ships crewed by Barbie and Han Solo and random plastic animals invested with Original Character Status by sole virtue of our loving imaginations, because really, that’s what they’re there for.

And then, somewhere along the way, we stop – not because the benefits of creativity, imagination and empathy are suddenly any less, but because we learn to prioritise official narratives over our own; or at the very least, to stop viewing our participation in the story as a natural means of extending it. We become self-conscious, aware of the boundaries of fictional worlds in a way we weren’t before. Which isn’t to say that the impulse to tell our own or hybridised stories goes away; far from it. But like Philip Pullman’s Lyra learning to reuse the alethiometer at the end of The Amber Spyglass, the transition from childhood to adolescence, or from adolescence to adulthood, often requires us to relearn consciously actions we once performed without thought; not because the actions themselves have materially changed, but because our awareness of their implications have – as, indeed, has the sophistication of our storytelling. Children’s playtales are an unapologetic Super Smash Brothers brawl of conflicting worlds and characters brought together for the sole purpose of having fun; and however hard we might try to recapture that sense of freedom as adult storytellers, our awareness of setting and context means we’ll construct these new stories differently.

What is Fanfiction?

At first blush, fanfiction is easy enough to define: as any fan-produced writing that utilises the settings and/or characters of other stories. Because fanwriters have no proprietary claim to their borrowed protagonists, fanfiction tends overwhelmingly to be produced and distributed for free – a literal labour of love. But the functionality of this definition is swiftly undermined when you consider the vast wealth of professionally produced stories which borrow from public domain, rather than copyrighted, narratives, or which reference mythological or cultural stories rather than professional fiction. In every instance, the impulse towards borrowing, reinvention and narrative interdependence is the same, regardless of whether the writer is drawing on copyrighted material or something else, and when you consider that one can simultaneously be a fan and a professional writer, it becomes increasingly difficult to draw any rigid distinctions between fanwriting and the other kind without hinging your definition, not on the type of story being told, but on whether the writer has permission to sell it.

Which, all things considered, seems rather backwards; not only because it makes the status of any given story potentially subject to change with time – as in the case of a fanwork based on a narrative whose copyright expires – but because it completely ignores the phenomenon of shared worlds and permitted adaptations. In 2011, for instance, author John Scalzi released Fuzzy Nation, a reboot of H. Beam Piper’s 1962 novel, Little Fuzzy. Though originally created as a writing exercise rather than a commercial project, Scalzi received permission from the Piper estate to publish his story, which makes it – I would argue – both a work of fanfiction and an original adaptation. Similar questions are raised by the existence of certain long-running narrative franchises, like Doctor Who or Superman, whose original creators have long since been replaced by writers raised as fans of the very stories they now control. That being so, to what extent can these communally created narratives be considered fanworks? What is more important to the definition of fanfiction – the writer’s status as a fan of the original creator, or whether or not they have that creator’s permission to sell new stories set in the same world?

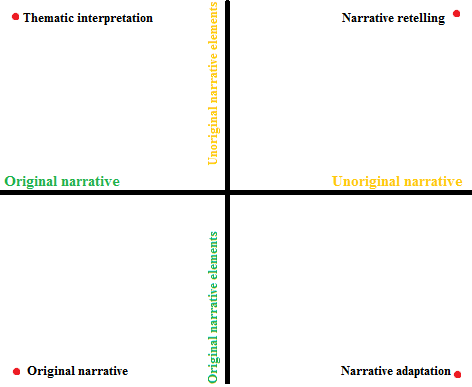

And what about stories which significantly reference other works without explicitly borrowing from them, or whose thematic structures are explicitly meant to evoke or echo those of another narrative? At what point does a new story cease to be inspired by another and become, instead, an interpretation of it? Instead of trying to look at fanfiction as the dichotomous twin of original fiction, perhaps we would be better served by envisaging an x/y axis of narrative interdependence whose arms account for original narratives/unoriginal narratives and original narrative elements/unoriginal narrative elements. For the purposes of this example, I’m defining original as invented by the writer, unoriginal as borrowed from the writings of others, and narrative elements as settings and characters. The end result looks something like this:

Again, it’s necessary to define terms: for these purposes, an original narrative is a story whose plot, settings and characters are the unique creation of a particular writer, with no elements borrowed from elsewhere, such as Avatar: The Last Airbender; a narrative adaptation is a story whose plot is borrowed from elsewhere, but whose setting and characters are unique, such as Clueless; a narrative retelling is a story whose plot, settings and characters are borrowed from elsewhere, but sufficiently altered to constitute a new work, such as The Muppet Christmas Carol; and a thematic interpretation is a story whose plot is original, but whose setting and characters are borrowed from elsewhere, such as Penny Dreadful. These are by no means perfect categories: indeed, the point of depicting them as quadrants around axis is to demonstrate their mutability in individual cases, and to highlight what almost amounts to a vaugeness paradox around the issue of thematic inspiration.

In the case of the 1995 film Clueless, for instance – which is itself a narrative adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma – the fact that the names of the characters are altered (Emma Woodhouse becomes Cher, George Knightley becomes Josh, Jane Fairfax becomes Tai) is not the primary difference between their iterations. Rather, and in deference to the fact that characters are a product of their environment, their personalities are adjusted to fit the context of a modern setting while still retaining the core romantic dilemmas of Austen’s plot. This being so, and without wanting to get overly philosophical, which elements do we consider as being more integral to the definition of the original characters – their names, their dilemmas or their personalities? Within the context of the narrative, is Cher still the same character as Emma because they ultimately have the same problem, or is she a wholly different creature, not because she has a different name, but because of the alterations to her personality? This is what I mean by mutability and vagueness: it is possible to argue the case both for and against, which means that, no matter how helpful our narrative interdependence graph might be in some respects, its deployment will always depend on our interpretation of the changes to, or originality of, particular narratives, and the extent to which we consider them to be linked to other works.

Consider, for instance, the ease and regularity with which modern books, movies, comics and TV shows all cheerfully encompass one another. The 2010 film Easy A is a deliberate tribute to the works of John Hughes, mentioning his various films, characters and narrative techniques while echoing them in a story that simultaneously references and parallels Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. In 2013, the lead characters in TV’s Supernatural took a break from killing monsters to watch HBO’s A Game of Thrones in an episode that also saw them teaming up with Dorothy Baum, aka Dorothy Gale, to save Oz by defeating the Wicked Witch. In the 2002 Futurama episode ‘Where No Fan Has Gone Before’, the original cast of Star Trek guest starred as themselves: which is to say, as actors forced to play their characters forever for the amusement of an alien fan. Last year, there was a crossover episode of The Simpsons and Family Guy, while back in 2009, Stewie Griffin had a cameo appearance in, of all things, Bones. Neil Gaiman’s classic Sandman series of graphic novels is practically a homage to the interconnectedness of stories, featuring characters as disparate as Hellblazer‘s John Constantine and the gods of ancient Egypt. And in one of the many defining scenes of Kevin Smith’s 1994 film, Clerks, the protagonists engage in a detailed discussion about the construction of the Death Star in George Lucas’s original Star Wars trilogy.

How are we to categorise these instances? Should we even try? Or is it more accurate and more practical both to acknowledge that narrative interdependence, rather than being an optional aspect of storytelling, is in fact an integral part of it – something to be analysed on the basis of its degree and intention rather than according to whether, under current copyright law, the writer can legally sell their work?

Because if we apply the concept of fanfiction to the above graph, it quickly becomes apparent that, while our original definition most closely aligns with the thematic interpretation quadrant – that is, with original stories featuring borrowed settings and characters – individual works can also fall under the auspices of narrative retelling and narrative adaptation; and even, arguably, in the case of published works that began as fanfiction but were altered to make them saleable, such as E. L. James’s Fifty Shades trilogy, original narratives.

Some fanfiction, for instance, retells the existing story with only a few crucial alterations, such as having two characters meet earlier than they do on screen or page, or resurrecting someone who dies in canon and rewriting later adventures to include their presence. Similarly, fanfiction might also make use of an established plot while populating it with different – though not necessarily original – characters. How might we categorise a story which combines the plot and settings of Harry Potter with the characters from Doctor Who? How do the four quadrants account for narrative length – for stories which retell fragments of existing plots, rather than entire narrative arcs? Is a plot still borrowed if a work only focuses on part of the whole, or alters some of the details? And how might we categorise fanfiction which, in addition to telling new stories about existing characters, also mentions or parallels other works into the bargain?

The point being, not only aren’t stories created in a vacuum – being both products of culture and cultural forces in their own right – but after a few thousand years of storytelling, it’s a comparatively rare narrative that doesn’t, however obliquely, acknowledge the existence of its fellows. Telling stories about stories, retelling old tales in different, original ways, or using pieces of existing narratives to inspire, build, subvert, recreate or otherwise enrich new ones is a fundamental aspect of storytelling, and always has been. Mythology and religion, regardless of whether we believe their tenets to be true or merely illustrative fables, are nonetheless human stories, and from the earliest days of the written word, our fiction has borrowed from them. You cannot understand tales like the Odyssey, the Ramayana or the Divine Comedy without acknowledging their interdependence with other narratives, both religious and secular, any more than you can analyse works like Wide Sargasso Sea, Ulysses or My Fair Lady without also studying the earlier novels and stories from which they draw their primary inspiration.

I’ll say it again: narrative interdependence is fundamental to the act of storytelling, and as such, compartmentalising fanfiction on the basis of its legal saleability alone gives the misleading impression that narrative borrowing is both the sole province of fanwriters and inimical to writing either successfully or for profit – neither of which is true.

Romance, Sex and Representation

All that being so, the universality of narrative borrowing within human storytelling doesn’t change the fact that what we generally refer to as fanfiction – that is, fan-created stories featuring characters and/or settings that exist outside the public domain – has a culture and a context all its own. Though the term itself was originally coined in the 1950s to indicate original but amateur works of science fiction, such as might have appeared in fanzines rather than professional publications, it more commonly came to be applied in the 1960s to stories written specifically within and about the Star Trek universe, spreading from there to other franchises. As Star Trek fanfiction is what famously coined the term slash or slashfic in the 1970s – a reference to the / used to signify romantic pairings between characters, such as Kirk/Spock – it’s by no means a stretch to suggest that an emphasis on sex and romance, while not integral to our current definition of fanfiction, is nonetheless a foundational aspect of many such stories.

Spirk

Even a cursory examination of the language of fanfiction tends to support this thesis. In addition to various terminologies used to describe the relationship between particular works and their source material – such as AU (Alternate Universe), indicating that the characters have been transplanted from their original setting to somewhere else; crossover, indicating the combination of multiple source stories or characters into a single coherent whole; and mashup, which tends to be a more riotous, less structured species of crossover – a slew of terms exists specifically to describe romantic relationships.

OTP (One True Pairing) indicates the writer’s preferred romantic pairing, whether canonical or otherwise; an OT3, by linguistic extension, is a similarly beloved threeway relationship. By contrast, a ship – contracted from relationship – is any pairing, canonical or otherwise, in which a fan feels emotionally invested, with the process of such investment called shipping and those who engage in it shippers, while someone with many ships, and especially if they potentially contradict one another (such as shipping both Kirk/Spock and Spock/Bones), is called a multishipper. Thus: all OTPs and OT3s are ships, but not all ships are OTPs or OT3s. Stories which are domestic or romantic but not sexual are called fluff, a term which has come to replace the older lemon; erotica or explicit sexual content is marked as smut, and a host of additional terms exists to denote varying types of emotional or physical relationship, such as hurt/comfort, UST (Unresolved Sexual Tension) or PWP (which stands variously for Plot What Plot or Porn Without Plot). Though slash itself is technically an umbrella term for any same-sex pairing, as the tradition began with male/male relationships, the term femslash has been subsequently coined to describe the feminine equivalent. Male/female pairings are sometimes referred to as het (short for heterosexual), but generally speaking, if you’re talking about sex and romance in fanfiction, you’re most likely talking about queer relationships.

Though there are any number of individual reasons as to why this is, speaking more generally, one of the primary functions of fanfiction is emotional catharsis: the creation of apocryphal stories intended to mitigate, subvert or otherwise redress perceived absences or failings in the canon. Whereas heterosexual relationships are common across all forms of media, queer narratives are far less common: ergo, fanfiction strives to supply what the source material either can’t or won’t. Throw in the generally poor representation of women in mainstream films especially, and you end up with a lot of emotionally intense stories where the most important relationships overwhelmingly exist between (apparently straight, usually white) men. This is the perfect breeding ground for slashfic ships: not just because emotional intensity is the bedrock on which fictional pairings are invariably founded, but because the lack of forced romantic pressure frees the characters up to engage in ways which, ironically, can be construed as providing a much more realistic basis for connection than exists between participants in many canon het romances.

One of the most ubiquitous formulas of modern film and TV, for instance, is the early narrative signposting of the protagonist’s endgame partner. In the first episode of TV’s Bones, we’re quite purposefully shown the sexually charged chemistry between the two lead characters, Temperance Brennan and Seeley Booth, the better to establish a will-they, won’t-they tension which, in this instance, lasts for six full seasons before developing into an ongoing relationship. In action films, by contrast, where the representation of women is especially poor, the ‘signposting’ tends to be nothing more than the inclusion of a single female character for the hero to eventually kiss or sleep with, the very fact of her presence made synonymous with her availability regardless of any other virtues she might have within the context of the narrative. Though Bones treats its female characters respectfully – and while I’m not inherently against the idea of relationships being signposted early on – there’s also a sense in which the general tendency to leave such pairings unconfirmed until the end of the story or as late in the series as possible, the better to build anticipation in the audience, can instead have the opposite effect: stunting the growth of the characters, denying them new and potentially more satisfying relationships, distorting the plot, and otherwise leading writers to sacrifice potential narrative gains for the sake of an arbitrary, early commitment.

While some such relationships obviously feel more natural or compelling than others (and while, as in all things, your mileage may vary as to which is which), when it comes to stories that either fail the Bechdel test or contain only one woman of note, there’s a weight of both cultural and narrative expectation that often leads not only audiences, but creators, to treat female characters as love interests first and everything else second – and where said romance is consequently signposted as endgame, the very fact of its inevitability can often have the paradoxical (yet understandable) effect of making the pairing feel emotionally unjustified, because the structural expectation of a romantic outcome has become an unthinking substitute for the sort of character development and chemistry that more realistically translates into actual romance.

One of the most pleasing recent examples of a female character being permitted to develop beyond these limits is Teen Wolf‘s Lydia Martin. At the start of the show, popular and beautiful Lydia is the object of everyman character Stiles Stilinski’s devoted affections, despite her longstanding relationship with Jackson Whittemore, a bullying jerk-jock. The confluence of these archetypes is so deeply driven into the cultural bedrock that we seldom, if ever, see them taken in new directions, and yet Teen Wolf does exactly that: even with Jackson out of the picture, Stiles and Lydia are allowed to develop naturally into close and significant friends who both see other people, free from the pressure of any overarching imperative that they eventually end up together. Stiles’s crush, rather than being treated like an underlying prophecy, is allowed to naturally fade away: he doesn’t compete with Lydia’s subsequent love interests, and all the narrative signposting usually employed to reassure the audience of an endgame romance is absent, allowing both the characters and the show itself to develop in newer and considerably stronger directions than it might otherwise.

More often, however, predetermined pairings are kept as a narrative staple, regardless of whether their eventual execution either does justice to the evolving characters or fits the eventual context. That being so, it’s hardly surprising that relationships left to develop naturally, without this sort of pressure, can often yield more interesting results – and given that queerness is both a human reality and something all too often absent from or elided within mainstream narratives, why should the gender of the participants stand in the way of fans envisaging them together?

In fanfiction, the saying often goes, we don’t ship according to gender, but chemistry – that amorphous but tangible intensity that makes the screen, or the page, or the game, light up. Which, given the preponderance of straight, white male characters in our media, especially in films and on TV, goes some way towards explaining why so many ships involve queer iterations of canonically straight, white men: because, statistically speaking, that’s what we’re given to work with. At the same time, however, if we’re committed to arguing that one of the primary functions of fanfiction is to address canonical imbalance, then the comparative dearth of fics with POC protagonists, or which give equal attention to queer, female and/or POC characters, is compelling evidence that, whatever our thoughts about diversity otherwise, fanfic writers can be just as biased as mainstream creators.

Elsewhere in the literary community, for instance, it’s often argued that readers shouldn’t pay attention to the identity of authors, but should rather seek out only works they consider enjoyable – a policy which, on the face of it, makes sense. But when, as is so often the case, this leads to the promotion and circulation of a staggeringly disproportionate number of titles by, again, straight, white, male writers, it becomes somewhat harder to argue that the selection process is a neutral as it pretends to be. By the same token, pleading ‘shipping on chemistry’ to defend against a lack of diversity only gets you so far. In both cases, there’s clearly a cultural thumb on the scale, nudging both audiences steadily towards one alternative while staunchly claiming to do no such thing, but once the problem has been pointed out, the onus for redressing it falls elsewhere.

That being said, it’s not a perfect analogy. In the literary example, the obvious solution for concerned readers is to simply seek out a wider range of stories; the equivalent action in fanfiction, however, is to give more prominence to characters we haven’t necessarily come to love, or in whom we’re less emotionally invested, which preference may well be a result of the fact that their narrative of origin has failed to explore their potential and thereby grab our attention. Reading more widely is comparatively easy, but when – as is the case with fanfiction – you’re producing thousands of words for your own pleasure and the enjoyment of others without any expectation of recompense, then suggesting that fanwriters expend more of this time and energy on characters that don’t necessarily interest them seems, if not unreasonable, given the context of the request, but possibly a counter-intuitive way of reaching the ultimate goal, which is more varied media all around. The fact that fanwriters can and do create works that are frequently more diverse than the original source material, and that the community itself is, by and large, actively engaged with questions of representation, does not obligate people who work for free, for pleasure, to conform to higher standards of inclusivity than is expected of creators who are actually paid for their output.

Korrasami

In fact, and despite the nominal uselessness of the theory of trickle-down economics, there’s an argument to be made for a theory of trickle-down diversity in the relationship between original content and fanfiction, inasmuch as greater diversity in the former appears to translate to greater diversity in the latter. Using the contents of An Archive of Our Own (AO3), a prominent fanfiction site, as a not unreasonable gauge of community interest, it’s noteworthy that the most popular ship for Avatar: Legend of Korra – a show where every character is a person of colour, and where the protagonist is female – is the femslash pairing of Korrasami (Korra/Asami Sato). The most popular pairings listed for Sleepy Hollow, a show with a majority female and POC cast, are similarly diverse, as is the case with Elementary, while the pairings listed for Orphan Black, despite the fact that all the main female characters are clones of each other, consists almost exclusively of femslash.

Though the overall number of works attributed to each of these shows is low when compared to the immense output surrounding (straight white male dominated) shows like Sherlock, Supernatural, Doctor Who and Merlin, this is arguably influenced by the fact that the latter franchises have been around for longer, and have therefore had more time to build up an established, dedicated fanbase. Whereas Supernatural and the new Doctor Who both began in 2005, with Merlin starting in 2008 and Sherlock in 2010, Avatar: Legend of Korra and Elementary only began in 2012, with Sleepy Hollow and Orphan Black following in 2013. The smaller number of fics available for Avatar: The Last Airbender, the similarly diverse forerunner to Legend of Korra, is arguably a better indicator of fannish bias, given that it started in 2006 – but with a majority of fanfiction focussed on romantic and/or sexual relationships between the characters, the fact that the heroes of Airbender are all underage is also a complicating factor (the characters in Legend of Korra, by contrast, are older).

Teen Wolf, however, which began in 2011, is both immensely popular and comparatively diverse, featuring a strong ensemble cast that includes a range of queer, female and POC characters as well as the requisite straight white guys, a variety that tends to be represented in its works despite the preponderance of white slash. More importantly for the numbers, it’s one of the most robustly represented fandoms on AO3, such that even though the most prominent femslash pairing, Lydallison (Lydia Martin/Allison Argent) has far fewer fics than the ever-popular Sterek (Derek Hale/Stiles Stilinski, which is, in fairness, one of the most beloved slash pairings of any modern fandom), it still has almost double the attributed works of Avatar‘s Korrasami. None of this is conclusive data, of course, but in terms of providing an overview on the priorities of fanwriters, it does tend to both confirm the current predominance of white male slash while simultaneously suggesting that diversity in the original content leads to diversity in fanfiction.

Sterek

Returning again to the idea of fanfiction as a medium which reacts to absences, missed opportunities and problems in the original narratives, however, and which is therefore fundamentally invested in doing what the source material doesn’t (or at the least, in doing it a different way), it’s important to consider other potential factors behind the dominance of white male slash. Particularly when it comes to films and TV shows, for instance, the default audience is usually assumed to be male, while the vast majority of fanfiction writers are not. As such, while the straight male gaze is catered to almost constantly, the straight female gaze seldom is, and while there’s some overlap between the queer female and straight male gazes – as Jane Lynch famously said of sexualised women on magazine covers, “As a feminist, I am appalled by these images. And as a lesbian, I am delighted!” – this leaves the straight female and queer male gazes both fundamentally unrepresented in mainstream culture. That being so, it makes a certain amount of sense that slash, as both a subversion of and a reaction to the absences of these gazes, would dominate fanfiction. Or to put it another way: given the fact that both straight and queer women are relentlessly sexualised in just about every form of media, why should it surprise us that fanfiction, which is both heavily romantic and female-dominated, frequently decline to make this a priority?

According to feminism, equality can’t simply be achieved by women taking on traditionally masculine roles; men must also adopt traditionally feminine ones, too. This principle extends to narrative depictions as well as everyday life, and as such, the arena of slashfiction takes on a fundamentally radical aspect when you consider how rarely romantic narratives are constructed about men alone, and how infrequently men are sexualised for female audiences. And while there’s an argument to be made that going tit-for-tat on sexual objectification isn’t the best way to progress, I’d contend that, generally speaking – and despite the problematic fetishisation of gay men by straight women that is certainly one of fandom’s uglier problems – the sexualisation of men in fanfiction tends to be much more sympathetic and respectful than anything habitually extended to women in, for instance, mainstream pornography, with which slashfic is sometimes compared.

By its very nature, slash is concerned, not just with the sex and physicality of the characters, but their personalities and backstories; as I’ve recently had occasion to mention elsewhere, there is no pornographic equivalent to the domestic fluff stories that fanfiction offers, or even the purely romantic ones, in which the characters are simply shown to be in a loving relationship without any explicit sexual content. Male characters in slash might be sexualised and, yes, objectified, but this is not their sole or even primary value to the readership – something which categorically cannot be said of the subjects of mainstream pornography, whose narratives, such as they are, exist exclusively to satisfy a sexual need.

This being so, and given the frequent use of fanfiction as a means of emotional redress for fans dissatisfied with aspects of the original content, there’s also an intriguing argument to be made – though not, I hasten to add, one to which I necessarily subscribe – that the greater the volume of fanfiction produced about a given franchise, the greater the level of fan dissatisfaction with the canon itself; or at the very least, with its romantic options. For instance: if queerness in fanfiction is written as a means of countering the blanket heteronormativity of certain stories, then there is much less of a need to produce queer fanfiction about narratives which portray queerness well. Whereas, for instance, when it comes to shows like Supernatural, which is famous for putting its ostensibly straight male protagonists in overtly homoerotic contexts without actually making any of them queer, there’s a much greater reflexive desire in the fandom to write corrective works; or at the very least, to explore those romantic possibilities suggested by the canon, but which the canon itself is apparently disinterested in confirming.

Omegaverse, Gender Roles, Kink and Biological Determinism

In mainstream romance novels and dating culture both, the idea of the ‘alpha male’ – an aggressive, stereotypically masculine man at the top of the pecking order – is one that’s gained a lot of social traction, despite its heavy reliance on sexism and gender stereotyping. This being so, the inclusion of literal alpha/beta/omega dynamics in paranormal romance novels with a shapeshifting element – that is, of human(ish) individuals whose hierarchical status and/or physical abilities within (for instance) werewolf culture is determined by some mystical combination of personality, genes and biological determinism – can be viewed as a logical extension of the phenomenon, especially given the fact that the alpha/beta/omega terminology was itself originally borrowed from our understanding of wolf packs. As I’ve previously noted, however, the fact that the alpha/beta/omega behaviours originally perceived in wolves have long since been disproved, with zoologists coining new language to replace these earlier terms, is yet to have an impact on the popularity of the adapted usage in paranormal narratives, and thus remains a defining aspect of modern werewolf stories in particular.

In fanfiction, however, the presence of alpha/beta/omega dynamics – often shortened to a/b/o – is used in a different way again. Such works, which are collectively termed omegaverse fics, make use of a shared biological mythology which, while differing in its details from writer to writer, nonetheless remains generally coherent across its iterations. While one might reasonably assume that the omegaverse, being a comparatively recent advent in modern fanfiction, began with Teen Wolf – a show which not only features werewolves, but is canonically concerned with alpha/beta/omega hierarchies, albeit nonsexually – it actually began as a prompt within the Supernatural fandom circa 2010, and has subsequently spread across into other fandoms (including, naturally, Teen Wolf).

The omegaverse postulates a version of humanity where the most important aspect of our sexual identity isn’t (male/female) gender, but whether one is an alpha, beta or omega, which designation typically ‘presents’ at puberty. Betas are biologically the most similar to real humans, and are generally portrayed as the calmest, most level-headed members of their society, being free of the more extreme biological impulses of alphas and omegas. Alphas of both genders can go into rut, while omegas have cyclical reproductive heats; alpha females can both impregnate and be impregnated, as can omega males; and alpha males, like certain male canines, can knot their partners during sex. Given the lupine influence, there’s also a strong emphasis on the relationship between scent and sex for all parties: everyone in the omegaverse has a unique scent which not only evidences their designation, but changes to reflect their emotional and/or sexual state, especially during heat/rut. Sexual compatibility is often determined by how appealing an individual’s scent is (or isn’t), and the concept of mates, or true mates – individuals whose biological/pheromonal compatibility as expressed through scent translates to an intense, immediate emotional bond – is usually a given. Mating bonds are usually confirmed with a bite on the neck, which has the power to change one’s scent, signalling whether an individual – and especially an omega – is either bonded or unbonded.

As the name implies, omegaverse stories are often primarily concerned with the romantic/sexual adventures of male omegas, and there are often strongly constructed parallels between the societal mistreatment and stereotyping of omegas and real-life prejudices against women. Which makes the omegaverse a subset of sexual fanfiction whose worldbuilding provides a context in which male fictional characters are subjected to the same biological processes, social restrictions and gender stereotyping as many women, up to and including pregnancy (mpreg), restricted access to birth control (heat suppressants), frequent sexual harassment, glass ceilings in the workplace, historical and ongoing oppression (both legal and social), stigma surrounding divorce or separation (broken bonds) and generalised assumptions about their sexual preferences. Regardless of whether omegaverse fics are (to borrow a phrase) your jam, or if, as many people do, you have squick around the idea of mpreg, there is nonetheless something inherently fascinating about the concept, not just of myriad strangers writing vastly different stories across multiple fandoms within a shared, collectively generated framework, but of women specifically creating a means of recasting male characters in traditionally feminine roles, not only socially, but physically.

As such, omegaverse fics tend to straddle an interesting – and intense – emotional divide. On the one hand, the focus on social justice and the persecution of omegas, which is purposefully analogous to real world sexism, lends itself to the discussion of some genuinely serious issues, such as rape, slavery and sex trafficking. Yet on the other hand, the more sexually animalistic aspects of the premise are often treated with an intensely pornographic fascination, and given the altered mental states brought about by heat, rut and scent bonding, this translates to a correspondingly high incidence of dubious consent (dubcon) narratives. Given the steady popularity of historical romance novels, whose female characters struggle to autonomously navigate love and marriage despite their lack of legal, social and sexual protection, it shouldn’t be so surprising that omegaverse stories reflect a similar tension/dialogue between submission and activism in a context where the one is simplistically taken to negate the other. Nonetheless, there’s a compelling paradox in the idea that omegaverse fics are just as likely to condemn such violent oppressions as to explore them in the context of kink or sexual fantasy, while the fact that both elements might be simultaneously – and deliberately – present within the same narrative is a testament to fanfiction’s versatility.

Also paradoxically, it’s interesting to note that, thanks to its mating/scent bond elements, there’s a deliberate correlation between sex and love in the omegaverse that’s almost the antithesis of mainstream pornography’s lusty, unromantic approach to fucking. Even in PWP fics, which often focus solely on characters mating while in heat or rut, the fantasy isn’t of sex without emotional attachment, but of sex as a catalyst for emotional attachment, even between strangers, and while it’s not uncommon for PNR narratives to employ similar soulmate/mating tropes, their execution can be complicated by the fact that the audience has no pre-existing reason to believe those characters should be together. But in fanfiction, where the reader invariably has a strong emotional attachment to a given pairing, the trope of romantic/sexual predetermination carries a greater, inherent burden of fulfilment from the outset.

What’s even more fascinating about the omegaverse, however – and which puts it in marked contrast to the vast majority of alpha/beta/omega iterations I’ve seen in mainstream paranormal narratives – is the extent to which questioning the biologically deterministic aspects of the premise is so widespread as to almost be part of the premise. An astonishing number of omegaverse fics take the time to address representational issues as part of their worldbuilding: what it means to be asexual when your body still wants to go into heat or rut, what it means for an adult to be ‘unpresented’, to have body dysphoria, or to have a gender presentation that doesn’t match their identity. Though omega characters go into heat, we frequently see them asserting, correctly, that this one aspect of their biology dictates neither their personality nor their skillsets, despite how they might be perceived by others. And though alpha characters can be aggressive and possessive, we frequently see them fighting the ‘knothead’ stereotype that says they’re slaves to their sexual impulses, which comes across as a ringing condemnation of rape culture – rather than, as is often the case in mainstream romance and PNR, their ‘alpha male’ status being used as a blanket means of excusing controlling, abusive or otherwise unacceptable behaviour Because Biology.

This latter distinction is, I suspect, due in large part to fanfiction’s culture of tagging – and therefore, of necessity, analysing – its own sexual content. Being disseminated primarily through sites like AO3, tumblr and LiveJournal, fics are usually found and sorted according to a tagging system of key phrases and search words, allowing readers to look for specific types of content while avoiding others. Similarly, fanwriters have the ability to annotate their stories chapter by chapter, or to bookend the narrative with notes about their intentions, in a way that mainstream writers don’t. The culture of tagging for trigger warnings especially means that fanwriters are encouraged to consider the question of consent, not just within the context of the narrative setting – that is, what the characters consider normal or acceptable – but as perceived by the reader, with a particular eye to noting any dissonance between the two states, the better to distinguish (sexual) fantasy from reality. But mainstream publishing, both romantic and otherwise, lacks an equivalent form of author/audience communication, and while this isn’t a loss in other areas, when it comes to discussions of sexuality, there’s a strong case to be made for fanfiction’s approach.

In particular, the fact that fanfiction encourages the tagging of dubcon sets it apart from mainstream romance novels, which often employ the same sexual/romantic tropes, but without the same degree of consciousness as to whether or not they involve a lack of consent, or whether consent, once established, has become compromised. This might seem like a pedantic distinction, but there is a world of difference between reading a story that appears to romanticise or justify abusive behaviour by failing to describe it as such in the narrative, and reading a story where, from the outset, the reader knows that the author knows there’s a difference, even if the characters don’t. In the former instance, it is much easier for readers, and particularly uncritical readers, to assume the behaviours depicted in the narrative are safe or defensible by virtue of their association with a hero or heroine otherwise characterised as desirable; in the latter instance, the presence of the tag is a signal to the reader that, however sexy something might seem on the page, that doesn’t necessarily make it okay in real life. (Should any evidence be required that such a distinction is beneficial to all parties, I would submit the fact that baby onesies declaring that “I pretend Christian Grey is my daddy,” among other such nauseating variations, are an actual thing that exist, as Exhibit A.)

As such, well-written fanfiction can be an incredibly safe way for readers, and especially women, to explore their own feelings about kink, dominance, submission and any number of other sexual preferences. Not only does the practice of tagging sexual content allow the reader to be absolutely clear within herself about the difference between (for instance) liking the idea of dubcon as an explicit fantasy and being guiltily aroused by controlling, aggressive behaviour, but in the case of male slash, be it omegaverse or otherwise, the act of identifying with a male character’s sexual preferences while still having a male character as the object of desire can be enormously helpful for some women when it comes to figuring out what it is we actually like. This might seem counter-intuitive, but given the fact that almost every sexual preference can be negatively culturally loaded for women in a way that it isn’t for men – women who like submission are bad feminists; women who like dominance are maneaters; women who like kink are crazy; women who don’t like kink are prudes – the act of focusing on male arousal sans female objectification can potentially allow women to shed their own cultural baggage, helping us to identify with a character to whom the same problems don’t apply; or at least, not in the same sense.

Or as I recently felt moved to say elsewhere, if it’s really surprising to you that many women have a heavy emotional investment in erotic fanfiction – a genre which, among other things, compulsively examines how sexual power dynamics between partners are reflected (or not) in other aspects of their relationship, and how this interplay is shaped by the expectations of both third party observers and the surrounding culture – then you should perhaps rethink your understanding of all these things.

Gazing at Straight White Men

The downside of this focus on men is, of course, a tendency to do so to the exclusion of women, both sexually and otherwise, with queer female relationships doubly losing out in terms of representation. This is a thorny issue, and one we would do well to be conscious of. That being said, it seems relevant to note that, along with straight, bisexual and pansexual women, lesbian and asexual women within fandom also identify with and/or emotionally invest in queer male relationships via fanfiction and fan culture, a fact demonstrated by, to pick just one example, the number of female couples who routinely cosplay as Supernatural‘s Destiel (Dean Winchester/Castiel). Which isn’t to downplay the fact that femslash is still proportionately under-represented, or suggest that female characters – and especially queer female characters – aren’t deserving of more attention, both in their source material and in subsequent fanfiction. Rather, I would suggest, there’s a sense in which many female fans find analysing male sexuality and masculinity to be less personal – and therefore, potentially, less exhausting and less painful – than the alternative, and while this still contributes to the same cultural bias that says men are inherently more worthy of such critical attention in the first place, the need to escape into characters who aren’t being judged in the same ways that we are, and who we can judge without simultaneously judging ourselves, is an understandable reflex.

Destiel

The argument is often made – or implied, at any rate – that straight, white, male characters are, in some sense, narratively neutral: that they are literal everymen, capable of being identified with and related to by any sort of audience in a way that queer, female or POC characters, who are perceived as being more ‘niche’ or ‘token’, just aren’t. This is, of course, complete rubbish; but the ubiquity of this attitude does raise the amusing possibility that the omegaverse is simply one way of taking the fallacy to its logical extreme. Namely: that if straight, white, cisgendered men really are a type of universal human, then creating versions of their characters who share only some or none of those attributes – or who can, as per the omegaverse, give birth and go into heat – might just be a natural expression of their true versatility. Only in fanfiction is the unassailable dreadnought of the straight white male character remade into Theseus’s ship, subject to racebending, genderbending, altered biological and sexual states, differing levels of ability and more sexual fluidity than a liquid Kinsey scale.

Minus the tongue-in-cheek perspective, however, it’s clear that any perception of universality or neutrality that does exist for straight white male characters is due, not to anything inherent in this combination of characteristics, but to the privileges historically afforded to such men within Western culture. That we have so comprehensively stigmatised all potential avenues of female sexuality with endless variations on the Madonna/whore complex, such that it’s now simpler for some women to channel their desires through male identification characters as a means of filtering out any internalised misogyny, is hardly a ringing endorsement of sexism-as-fallacy. That we have such a collective, historical deficit of characters who aren’t straight white men to make up for, and a cultural habit of resorting to stereotypes when we try, is proof of a longstanding lack of neutrality in narrative, not its opposite. That we are making a conscious effort to redress these imbalances via the creation of new, more diverse content doesn’t change the fact that we have a long way to go, and it doesn’t mean we’re wrong to develop coping mechanisms in the interim.

Similarly, straight white men have been touted as human universals for so long that, even when we know better, there’s a practical (if paradoxical) sense in which our very enthusiasm to change this perspective can end up supporting it. When the representation of other groups is so small and stereotyped by comparison, our eagerness to encourage more positive portrayals can become a double-edged sword, the weight of our expectations for new queer, POC and/or female characters causing us to hold them to higher standards than we ever expect of white guys, and – as a direct consequence – to be more sharply critical of them.

Which means that, as frustrated as we can become with straight white male narratives, and as much energy as we’re wont to invest in discussing their many problematic elements, there’s also a sense in which returning to them can constitute a critical vacation. Our disappointment at their failings is ingrained enough that we can almost laugh about it: the lower our expectations, the less it hurts when a given franchise once again fails to meet them. Like the comments section on any YouTube video or article about feminism, we already expect so much to go wrong that there’s a kind of freedom in simply declining to engage, or in focussing exclusively on what positives exist to be found. But when a newer story – one that perhaps inspires us to hope; which lets us trust that maybe, this time, we’ll see ourselves represented well – fails to deliver on its promises, even if only once, the pain is amplified a hundred times over. It’s the difference between being beaten up by a bully and beaten up by a friend: we expect the former to hurt us, and while that doesn’t make the pain any less, we can usually take steps to protect ourselves in advance. But attacks from friends – from the people we trust – can hit us where we live, and even though the physical damage might be lesser, the hurt can be just as intense.

To quote the anonymous wisdom of the internet, the saddest thing about betrayal is that it never comes from your enemies.

Conclusions and Paradoxes

If, in the course of this essay, I’ve asked more questions than I’ve offered answers, it’s because, despite the amount of time I currently spend writing, reading and thinking about fanfiction, I’m still in two minds about many of its issues. I would love to see more and better representations of POC characters in particular, and for more discussions to be had around the fact that, despite the popularity of slash, there is a real elision of men and women of colour. At the same time, and as much as I believe that there’s an individual onus on fans to engage critically with the media they consume, I find it harder to argue that this implies a commensurate obligation for fanwriters to create more and different content than they are already, given that, as they’re working for free, they’re not technically obliged to do anything.

When creators are paid for their output – and especially when said output is popular and widely-disseminated enough to influence the creation of more new works – it becomes somewhat easier to argue that writers have a responsibility towards diversity, if only on the basis that profit is a mechanism with heavy traction across all areas of society. But in the case of works that are made for free, for pleasure? As much as I’d like to believe that all writers, regardless of whether they’re being paid, feel a certain responsibility about the potential impact of the content they create, there is no objective reason why this should be so – and when the content in question is so routinely mocked as unimportant, unliterary and unsavory by mainstream outlets, why shouldn’t its creators strive to please themselves ahead of anyone else, when there’s no way of predicting if a given piece will get a bare handful of views, or tens of thousands?

Which brings us back, full circle, to the idea that fanfiction is currently distinguished as such, not because it’s the only form of literature to make use of narrative borrowing, but because its writers cannot legally sell their work without, at the very least, changing some key details – and where such work is produced and distributed for free, it becomes inherently more difficult to hold it to any kind of collective, critical accountability, not because such criticism is unwarranted or without benefit to the community, but because its usual power to influence any future publications is wholly dependent on whether or not the writer is both listening and amenable. Bad reviews can sink a planned trilogy after the first instalment when money is involved, but if the creator is reliant on third parties for neither funding nor distribution, what negative outcome can criticism threaten that isn’t already an inherent part of the process?

Which is, in a simultaneous paradox – and I seem to be using that word a lot; and with reason – one of fanfiction’s greatest strengths: that it lets you try literally anything. Fanfiction allows writers to take the sort of narrative risks which, in paid or professional contexts, are frequently frowned upon, and which – again, paradoxically – can sometimes be all the more popular for being unfamiliar. I’ve seen fics clock in at under a hundred words and over a million; fics whose entire plots consist of a couple being domestically content, or which are nothing but unremitting damage and heartbreak. Given the ability of readers to subscribe to an ongoing fanfiction, receiving digital updates when a new chapter is ready, I’d even argue that the medium is closer to the classic type of rapid serialisation employed, once upon a time, by traditional newspapers than even current digital magazines, whose longer editorial times mean most new issues are monthly or quarterly, rather than weekly or daily, can manage, lending to one of the most immediate production/feedback relationships of any creative medium.

Fanfiction is old and new, smutty and sweet; it is flawed and complex and achingly human, and we will continue to discuss it for as long as we discuss stories – because if narrative borrowing can be reasonably considered an integral part of storytelling, then whatever its faults and professional status; whatever its biases, blind spots and mainstream perception, fanfiction is and will remain a pure, joyful expression of our impulse to tell stories about stories, an endless cycle of narrative interdependence that, for all its complexities, is also fundamentally simple.

As a child, my mother read me stories, and whenever they ended, my response was always the same: I’d ask, What happens next? Even children understand that the reality, the importance of a story transcends its physical endpoint: the characters don’t cease to matter just because the credits are rolling any more than our emotional involvement ends with the closing of a book.

And so we go away, and we tell our own stories to fill the gaps.

And so we always have. And so we always will.

About the author: Foz Meadows is the author of two YA urban fantasy novels,Solace and Grief and The Key to Starveldt, both with Ford Street Publishing. She is also a contributing writer for The Huffington Post and Black Gate, and a contributing reviewer for Strange Horizons and A Dribble of Ink. She has been published in Apex Magazine and Goblin Fruit, and in 2013, she was shortlisted for a Best Fan Writer Hugo Award for her blog, Shattersnipe.

An Australian expat, Foz currently lives in Scotland with not enough books, her very own philosopher and a Smallrus. Surprisingly, this is a good thing.

25 Comments

E.Maree

January 13, 2015 at 5:56 amAbsolutely fantastic article. I love that Foz didn’t shy away from the problematic aspects of fanfic, but also considered that fanfic writers are doing this for fun and that naturally affects what they cover.

Estara Swanberg

January 13, 2015 at 8:35 amYou should do this as a lecture, preferably at TED ^^, or maybe you did it at Loncon, there was so much stuff I didn’t see it all. Outstanding – from the historical background to the introduction of terms to the thoughts about ramifications.

Sherwood Smith

January 13, 2015 at 9:26 amWhat a terrific essay. And yes about the history of fan fiction: a few years ago I was reading Ariosto, and it hit me that Arthurian was nothing more nor less than pan-Euopean fan fiction. A thousand years of it.

I think the female gaze has been primarily important in romance, ever since Jane Austen wrote witty, trenchantly observant books in which the female POV mattered. Female writers have taken up that torch ever since (Elizabeth Gaskell directly addressing the question in her brilliant Wives and Daughters) but the twentieth century publishing world saw fit to constrain female narratives to het romance and domesticity until relatively recently.

It’s worth nothing that writers such as Louisa May Alcott and others also wrote what was dismissed as “potboilers”– works in which females are not constrained by the social rules of being a “lady”. They are every bit as wild as Emily Bronte’s work.

I’ve seen fan fiction’s rise during the late sixties and seventies as female writers sidestepping mainstream publishing’s constraints to write what they wanted to read. And they found an audience that is still growing.

Ana Maraya

January 13, 2015 at 11:14 amI want to say thank you for this essay.

I think you have beautifully and gently explored the culture of fandom. As a part of fandom, I can see your respect for the community, your respect for the subversive and corrective and therapeutic properties of fic, and even beyond that, your loving examination of fandom’s problems.

This essay was a delight to read – I savored every one of the 45 minutes it took me to carefully walk through this, highlighting and digesting each impeccable sentence. When I read fan meta, which I LOVE to do because it’s so validating, I often pick out my favorite sentences and and e-mail them to myself so I can save and re-read them whenever the mainstream pokes it head in to pick on fandom again.

I had so many favorite parts of this that I eventually gave up on the e-mail and opened word document to bullet point everything. I loved your discussion of the invisible “cultural thumb” that is omnipresent even in fandom, and your grappling with the obligations/nonobligations of fan authors. I loved your characterization of slash fic as “fundamentally radical,” with women essentially producing and consuming their own pleasure narratives in this space, reversing and interrogating the male gaze, essentially wielding the narrative power that they are denied in mainstream media. Women writers and readers of fanfic transgress many of the strongest cultural rules that comprise the foundation of the patriarchy’s power. We unabashedly question gender, desire, masculinity/femininity, sex and submission. What could be more radical than that?

I loved your exploration of Omegaverse and share your admiration for its especially subversive world building. Omegaverse is literally dripping in political content, with authors constructing painfully familiar power structures only to allow characters the opportunity to dismantle them. I read an outstanding Omegaverse fic where the a male omega rose to captain a sports team, and was faced with the systemic suspicion of a society that privileged Alphas in sports. It was a classically satisfying trope subversion fic, but my favorite part was when an Alpha character said something along the lines of, ‘do you hate being an omega?” and the main character responded – “no, I’m not ashamed to be an omega, omega’s aren’t weak we’re taught to be shut up and be quiet, it’s society that’s got the problem, not us.” That slice of perfect societal commentary is why I love fic. Because I read omega verse, and then I turn back to real society and have stunning epiphanies like, “Holy god. Gender roles are entirely fabricated. Literally they are just a fake and created as a/b/o dynamics are.” and then I need to sit down and fan myself weakly as I contemplate the role of the patriarchy in my everyday life.

This comment is essentially an essay of its own now so I’ll try to wrap this up. I think this piece of writing is a fabulous, incredible examination of what/why fanfic is. In fact, it’s my new go-to explanatory article if I ever am outed to the point that I need to explain fanfic to an outsider. Seriously, I’m saving this thing on file and plan on refusing to discuss fanfic with any non-fanish person who hasn’t read this. Final comment: The one thing I wish you had addressed more in this article is the profound stigmatization of fandom in media, and the preservation/dissolution of fandom as a semi-secretive subculture (relating to some very current concerns about the fourth wall and the mainstream media “discovering” fandom.) I’m sure you have a thousand thoughts on why fandom is so negatively characterized in the press, and what, if anything, fandom should be doing about that (ignoring it? trying to change it? Ignoring it some more?).

But seriously, thanks for this. Apologies for the novella comment.

Alex

January 13, 2015 at 11:56 amThis essay is, of course, outstanding. One other thing I’d like to discuss specifically is the utility of fan fiction to the author, not just as a means of creative expression, but as a means of practicing in front of a built-in audience. Think of it like… opening for a popular band, perhaps? As an example, I’ve got a Korrasami fic on AO3 that, in less than a month, has been read almost 6000 times. Though this is hardly a remarkable number, I don’t think I could get any of my original fiction in front of 100 sets of eyes, at the moment. I’ve also received both praise and well worded criticism for this work, which I’d never get otherwise. I’m the same would-be writer, of course. But by writing fan fiction, I can A) Be read, which selfishly, feels good; and B) Get reactions from people who inherently care about the world in which you’re operating. These things have value.

Kisatsel

January 13, 2015 at 2:41 pmThis was a great read! I found your discussion of omegaverse particularly interesting. Fandom is such a unique space, that you can have a whole raft of stories existing in dialogue with each other, which on the one hand are essentially kinky erotica where men knot each other and have self-lubricating anuses, but also frequently contain nuanced and powerful exploration of gender roles and queerness from a female perspective.

Also interesting to note that slash fandom has been exploring those kind of power dynamics and gender roles for quite a while: BDSM AUs where every individual identifies as dom or sub in the same way as they do with genders have been a thing since Stargate Atlantis fandom, and though I’m kind of vague about this because I’m less familiar with Sentinal fandom, I know that the Sentinal and Guide dynamic in fic from the 90s onwards was developed by slash shippers into a sort of similar soulmate bond where the Sentinal occupies the more traditionally masculine role of protector and the Guide the more traditionally feminine role of supporting the Sentinal’s physical/emotional wellbeing and being more fragile.

There was a period where I was desperate to see fictional representations of bisexuality, and in relatively recent slashfic being bi isn’t just prevalent it’s totally normalized, which provided a way for me to feel comfortable within myself while also not thinking about myself at all. I’m also super interested in the parallel developments of the shift towards gay relationships becoming more accepted in society, greater LGBT representation in TV/movies plus the increasing criticism of ‘queerbaiting’, and fanfic writers moving from often writing the ‘gay for you’ trope where their true love ‘overcomes’ their straightness to more frequently reimagining straight characters as bi.

Bookgazing

January 13, 2015 at 3:51 pm‘As much as I’d like to believe that all writers, regardless of whether they’re being paid, feel a certain responsibility about the potential impact of the content they create, there is no objective reason why this should be so…’

I’m reminded of Maureen Johnson saying that she and many women grew up being told that stories about boys were super awesome. I’m one of those women. I like a lot of stories about dudes and dude worlds (especially when dudes go to sea) because those stories are fun and that’s cool. But I used to sometimes privilege those stories, and privilege seeking out those stories, over just as awesome stories about women because I’d been taught that stories about men were more awesome than stories about women. I felt I would automatically enjoy the stories about men more and so didn’t see why I would cut down that enjoyment by reading what to me seemed like ‘substandard’ stories? Which, yeah, was a huge problem.

Recognising that my thinking was off doesn’t mean I was wrong about what I enjoyed, that the stories I like about dudes weren’t cool, or that I had to stop seeking out or creating those stories (huge Reese/Finch POI shipper here) but it did make me sit back and think about why I wasn’t creating, taking in and loving other kinds of stories too. That was really just valuable for me and has led to a big shift in how I consume media.

I guess when I relate this to fanfic I think we don’t all have to stop liking or creating certain stories because of how their substance relates to real world representation, but I might say if all we’re liking and creating is one thing maybe we want to ask why we’re only making that one thing. And maybe just asking that question will open up new worlds for us – new things we want to explore. It doesn’t have to be a negative – ‘why don’t I stop creating these kinds of stories that I love’ – instead it could be a simple ‘why aren’t I interested in making other things as well’.

There will be a variety of answers to that question and in many cases people will find that staying creating one kind of romantic relationship etc. is right for them. As you say, a lot of fanfic is romantic or sexual and people like what they like there’s that side of things to consider as well. Also, a lot of people see women writing slash as a form of radical writing (and I agree with that on many fronts). How do we navigate these questions and examine our work without self-shaming ourselves when we’ve already potentially been hard on ourselves about wanting to write fanfic and we’ve been shamed by the media and others? It’s really difficult because I would never want people to feel like they lose that joy of creating. So, full acknowledgement that my way can’t be everybody’s way, nor is it perfect and I still have a really long personal media journey in front of me etc, etc, disclaimer, disclaimer. Just thoughts I’ve been mulling really.

A.B.

January 13, 2015 at 6:40 pmJust some corrections. The term “lemon” actually means a pornographic fanfic, and has for a long time. Also, if you look on Fanfiction.net, you’ll see that Avatar: the Last Airbender easily outstrips Legend of Korra in the quantity of fanfiction, and most of both these fandoms output consist of het fic.

Dolorosa

January 14, 2015 at 10:29 amThis is a fantastic post that really articulates the contractions and complexities of fanfic, its writers, and the community that supports them.

One thing that’s always struck me, though, is the role various individuals and subcultures within fic-writers can play in shaping our expectations and perceptions of fic as a whole. That is to say that there is no single fanfic-writing community, but rather hundreds of interconnected, overlapping communities, and the conventions of one community are going to shape the attitudes of that community’s members as to what fanfic is like. The example of the difference in ATLA fanfic between Archive of Our Own and fanfiction.net is a good one, and chimes with my own experience of ATLA fandom being primarily het, and congregating mainly on ff.net and Livejournal communities. Of course, the ATLA fic on Archive of Our Own paints a very different picture.

I also find the role individual writers play in shaping the fannish output of a community as a whole absolutely fascinating. One well-known and talented writer, writing the right fic at the right time, can end up creating a juggernaut pairing, a certain popular dynamic for that pairing, and various tropes within the fic produced by that fandom. These elements obviously speak to a lot of fans, or else they wouldn’t be popular and replicated, and I find the process by which such replication happens really intriguing.

Speaking as someone who’s mostly interested in stories about women, and whose interest in this regard extends into fanfic as well, it is possible to engage primarily with fanworks focusing on female characters, it’s just that there’s a lot less fic to read, fewer readers with whom to share a community, and the fandoms tend to be different to those in which a lot of (primarily) slash-reading/-writing fans congregate. More Orphan Black, Orange is the New Black, and Pretty Little Liars, less Teen Wolf and the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The brilliant thing about fanfic, which you highlight excellently here, is its infinite variety, meaning there’s space within it for all of us.

Danny Adams

January 15, 2015 at 7:49 pm“Consider, for instance, the ease and regularity with which modern books, movies, comics and TV shows all cheerfully encompass one another. ”

And farther back than that. I’m thinking in particular of Philip Jose Farmer’s Wold Newton series, in which he created a family tree linking many of the great 19th and 20th century classic and pulp heroes, from Sherlock Holmes and Captain Nemo to Tarzan, Doc Savage, and the Shadow.

From the world pool: January 16, 2014 |

January 16, 2015 at 11:40 am[…] to its position in terms of male/female gaze and the politics of gender relationships to…. Wow. Foz Meadows – Thoughts on Fanfiction. “Fanfiction is old and new, smutty and sweet; it is flawed and complex and achingly human, and […]

Links of Interest : January 16, 2015 « A Modern Hypatia

January 16, 2015 at 12:57 pm[…] Foz Meadows on fanfiction. […]

Arisia: Queering Up Canon panel | Fanfic Journal

January 20, 2015 at 12:05 am[…] replicating heterosexist gender roles, could those really be queer? I think it was here I mentioned a guest post at the Book Smugglers by Foz Meadows which was super-long and probably the first half could be skipped for people who were familiar with […]

Christy Broy

January 20, 2015 at 1:51 pmFoz, this is a wonderful article that perfectly illustrates the history and current state of Fanfic. I have been moved to put thoughts on paper, so you know you did well.

Re: Fanfic- real world application.

I would agree with your assessment that it is difficult to separate the fan from the writer. Not only in cases where someone is writing within or about a particular fandom, but possibly in regards to all fiction writing. I know that I have absorbed more characters and settings and circumstances from pop culture than can confidently be quantified and every single thing that I write is informed by that in some way. We as a society, obviously more so in some geographical areas than others, are raised with at least the most basic understanding of a few fictional worlds. I would argue that a vast majority recognize elements and faces from the Star Wars and Star Trek franchises and more recently Harry Potter and the re-popularized Marvel Universe.

Now, recognition by itself does not create an influence, but the characters are archetypal- one doesn’t need to know the detail to “get” the story. In this way, we are subconsciously aware of them and there is no doubt in my mind that elements seep through the cracks into writings and musings even when we do not realize it. You create a story surrounding a broken and roguishly handsome man who travels with his brother fighting evil. He turns out to be reminiscent of Han Solo and the brother seems very Sherlockian in his love of research and his encyclopedic knowledge. They are a little bit Hardy Boys a little bit Butch and Sundance. So, are Supernatural’s Winchester Brothers completely autonomous creations or constructs of a writer steeped in pop culture knowledge? I would argue that we are -most of us at least- unable to avoid informing our writing in this way with our history as “fans”. Following this argument to it’s obvious conclusion: Almost everything can be considered fanfic as it is written by fans of something.

Everything is an AU of the fictional world crossovers in our collective minds.

Who is to say that when we speculate on what direction a particular franchise or series might take, or share with friends and co-workers what we hope might be in their upcoming story lines (fleshing out our ideas with enthusiastic detail), that even then we are not participating in a long tradition of oral “fanfic” storytelling?

Re: Fanfic- Shipping

I was shipping before it was a conscious thought. He-Man and Teela were totally making out by the rocks in my backyard. When it snowed, I starred in epic dramas as Leia delivering tragic lines to Han Solo whose role was played by a tree. I spent years gnawing my fingernails over Mulder and Scully. I stayed up late Friday nights to see if John Crichton was gonna man up and make out with Aeryn Sun.

Though I had been constructing it in my head for decades, I never actually read any fanfic until my early 20’s and I will admit it was few and far between to find great works. I can tell you that my number one requirement for a fic was my then OTP. Nowadays wonderful writing is available in droves. I myself only read one fandom’s fic, but it is hard to miss how much is out there to be had across many genres.

I would posit that there is much more fic including romantic relationships not fully realized or addressed in canon than fic that mirrors canon completely with no divergence in these relationships. It is clear to see that there are unexplored stories that the creators of these shows, films, novels are not delving into which hold a lot of interest to the fans.

One would hope that the ‘Powers That Be’ would recognize this and take a lesson from the fans at some point and flesh out some of these relationships in an honest way. I stare at my TV frequently mumbling “I am not making this up am I? These two are totes in love.”. Wishful thinking worked for Mulder and Scully, but I hold out no hope for such bravery in the case of my OTP, which happens to be a slash pairing in a hetero white male wonderland.

My point is this: When it comes to shipping, sail away people. And to the fanfic writers: Just because the creators aren’t brave enough to do the thing, doesn’t mean it’s not the natural progression of the story. You are just as well informed a fanfic creator as they are, your fic is just unhindered by dollar sign and a fear of the board room. We are all ‘Fanfic’ writers, they just can’t seem to hold on tight enough to the ‘Fan’ part.

Teen Wolf: Subversion, Masculinity and Gender | shattersnipe: malcontent & rainbows

January 21, 2015 at 9:37 pm[…] dynamic is also evident in Stiles’s relationship with Lydia. As I’ve recently said elsewhere, one of the most satisfying of Teen Wolf’s trope subversions is the steadily developed […]

Anna

February 3, 2015 at 8:13 amI have a problem with fanfiction and the huge lack of open discourse exactly where you so nonchalantly call it “tit-for-tat sexual objectification”.

Not only that there are large percentages of underage porn among the sexual content of fanfiction, illegal even in written form in most of Europe and definitely also in New Zealand and Australia, which remains completely unaddressed.

No, there also is exactly that express fetishization of mostly underage or teenage gay males by what appears to be a foremostly middleaged female writer/readership. This, as also was noted by commenters further above, by now almost as a rule goes hand in hand with depictions of rape, non-con and torture, all of which often are presented as erotic.

That’s not just a tit-for-tat sexual objectification, on par with how straight white males objectify women. It goes far beyond that. Where Kirk/Spock, Ellison/Sandburg or Starsky/Hutch at least were adult men and tended to be written with some agency even within H/C and woobie tropes, my impression of more recent fanfiction is not at all similarly benign, in particular where audiences and writers differ largely from the portrayed age group. A 13-year-old teenager romancing Stiles is different from a 40-year-old woman writing rape and torture for the same character, or an even younger Draco Malfoy for instance.

The lack of open and critical discourse regarding this is most intriguing. Yet even a 20 pages long essay doesn’t mention it with a single word. As a consequence I might pose it that a second problem with publishing these fanfiction stories would be questions of illegality in another department than who owns the characters.

Limits, Assumptions & Narrative | shattersnipe: malcontent & rainbows

February 16, 2015 at 10:54 am[…] the concept of fanfiction: stories written about settings and characters with which we’re already familiar, but which […]

Jewy fanfic!

February 19, 2015 at 4:12 pm[…] addressed, as far as I can tell. But no one has to fight ALL the battles. And in the Book Smugglers essay I cited in the Tablet piece, novelist Foz Meadows makes an excellent point about why female […]

Franzen, Feminism & Fanfic | shattersnipe: malcontent & rainbows