This month on Trope Anatomy 101, Carlie St. George examines the concepts of terror, fear, and standard portrayal of heroism in popular culture.

Trope Anatomy 101 is a monthly column in which familiar tropes, particularly in speculative fiction and pop culture, are broken down and discussed by new regular contributor and author Carlie St. George.

Beyond The Standard Heroic Range

Last year, a strange thing happened: I watched a super smart, telepathic, and mind controlling gorilla menace a police detective on a live-action television show.

The Flash was not my introduction to Gorilla Grodd. I was familiar with him from his appearances on Justice League and Justice League Unlimited, and admittedly, he was never one of my favorite villains. But on a cartoon also featuring a murderous alien supercomputer, the Olympian god of the underworld, and a demon bound to a disloyal knight from King Arthur’s court, Grodd didn’t seem so entirely bizarre. Prior to 2015, however, I never would have thought that such a fantastically outlandish character would ever appear on a live-action TV show designed to hook geek and non-geek fans alike. I remember watching the episode, not knowing what to expect.

And that’s when I saw something that surprised me even more than an evil gorilla with mental superpowers: the police detective in question, Joe West, showed abject and unrestrained terror in the face of his worst fears.

It’s a well-documented and unfortunate trope in Hollywood that “real men don’t cry,” not for any reason, particularly in action movies or TV procedurals (with or without a speculative bent). Sometimes I feel that the open emotional display of terror, even more than grief, is used as a sign of emasculation and weakness. Men who show any overt indications of fear are most commonly relegated to comic relief because, too often, bravery is considered synonymous with fearlessness, ergo the best, most masculine heroes are those who feel (or at least display) very little genuine fear. I, personally, am not quite as interested in that kind of hero, because real men DO feel fear, and the only time men can be brave is when they’re afraid, just like Ned Stark and A Game of Thrones taught us.

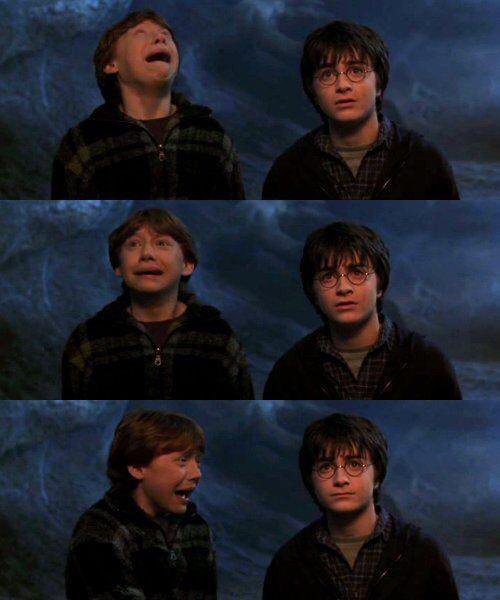

Now, it’s not that men don’t express fear in movies. Far from it, actually: men are afraid all the time; they’re just usually scared about someone else dying (often a love interest, or sometimes a child). When men are scared for their own lives, though, Hollywood seems far more comfortable turning their anxiety into a joke. Often you find that the more extreme the distress, the more exaggerated and humorous the performance: think Private Hudson’s memorable panic in Aliens or Brandt’s deep reluctance to jump into a giant computer array in Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol. This also applies to pre-teen boys; consider Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. Anyone unfortunate enough to come across a veritable horde of giant, man-eating spiders would be scared out of their minds–certainly if that person was also an arachnophobic twelve-year-old–but while I never read Ron’s terror as a joke in the book, the moment played differently for me on film. Rupert Grint’s facial expressions are not technically inaccurate to the text, but the tone of the scene itself seems far more comical, especially when one compares Ron’s abject horror with Harry’s considerably more restrained fear. We’re invited to laugh at Ron’s exaggerated facial expressions, just as we’re invited to laugh at Hudson’s hysteria or Brandt’s prolonged hesitation.

And there’s nothing particularly wrong with that; fear can be and often is funny. I’ve rewatched that Ghost Protocol clip several times now; I quote “Game over, man! Game over!” way too often in my own daily, non-alien filled life. But it seems to me that humorous fear has almost become the default, that outside of the horror genre, we generally expect terrified men to be a joke–and so it seems often noteworthy or even strange when those expectations are subverted.

Let’s go back to Joe West for a moment. There is some intentional humor in this scene: I, certainly, am incapable of watching a massive gorilla lean in and ominously declare, “GRODD HATE BANANA” without giggling. But Jesse L. Martin’s terror is played straight, and his performance is very atypical from what we’ve been led to expect from a grown man and police detective. Joe stutters, screams for help, and bursts into tears, begging, “Please,” as Grodd forces him to point a gun at his own head. Like Ron Weasley with spiders, Joe is frightened of even normal gorillas who are incapable of telepathically compelling you into suicide, so of course this experience is especially traumatic for him. But his reaction would have been incredibly realistic for anyone to have had in the face of such imminent peril . . . so why is it so rare that we see other men breakdown this way? Because while mind-controlling gorillas certainly aren’t the norm in movies and television, instances where heroic men must face down death occur relatively frequently in cop shows, superhero shows, action movies, etc. The danger is no less great, and yet it seems to me that the majority of heroes are boxed into a very limited range–let’s call it the Standard Heroic Range–of how much genuine fear they’re allowed to express, particularly when compared to how humans actually respond when they’re afraid.

Let’s look at a few ways a character might respond to anxiety, panic, and/or danger, and see if these response fit inside or outside this Standard Heroic Range.

SCREAMING/SHRIEKING

Possibly acceptable, depending on how long the scream goes on for, how high-pitched it is, and what’s causing the scream in the first place. Yelling in sudden surprise or alarm is relatively normal, such as Rick O’Connell in The Mummy, who jumps back with a startled “Whoa!” when he sees Imhotep for the first time. Likewise, a hero falling to his supposed demise (Kirk and Sulu, for example, as they’re about to splatter on Vulcan in the 2009 reboot of Star Trek) is usually acceptable, but again, it’s all about that pitch. Higher notes are generally fine if the hero is screaming in pain (especially while being tortured; think Han Solo in The Empire Strikes Back) but a man shrieking in fear is nearly always played for laughs. It’s an incredibly common trope on television; see Cisco Ramon on The Flash, Fox Mulder on The X-Files, Dean Winchester on Supernatural, and Shawn and Gus on Psych.

And outside horror movies, I’m hard-pressed to think of any men who deliver the kind of drawn-out, Hollywood scream you get from, say, Carol Marcus in Star Trek Into Darkness or Lydia Martin on Teen Wolf. (Admittedly, Lydia is a banshee, so she generally has semi-plot related reasons for this. Still, I’m finding it difficult to come up with men on TV who scream with this kind of intensity or frequency.) Even within the horror genre, honestly, men are far less likely to scream as long, loud, or as often as women. It happens, of course, but I wouldn’t call it a staple of the genre; there’s a reason we don’t often talk about Scream Kings in pop culture.

HESITATING/FREEZING UP

Likely acceptable, depending on what the threat is and how long the hero takes to recover. Ethan Hunt in Mission Impossible – Rogue Nation shows signs of mild apprehension when he has to jump into a spillway, hesitating briefly before diving in. The performance is subtle, not exaggerated, though, and he doesn’t hesitate for nearly as long our aforementioned supporting hero Brandt in Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol. In general, the longer a male character freezes up, the more likely it’s a supporting character; take, for instance, Scoggins in Deep Blue Sea, who understandably panics when super smart mega sharks start eating people and has to be talked back into action by our considerably more stoic hero.

A notable subversion to this is Tony Stark in Iron Man 3, who suffers from insomnia, anxiety, and multiple panic attacks. I really appreciated this subversion because, as a fan and a writer, I am particularly obsessed with emotional continuity and was thus happy to see Tony struggling after the events of The Avengers. I’ve spoken to some people who felt his anxiety was approached too lightly, which is a valid criticism, but I personally didn’t feel like the film was trying to make one big joke of Tony’s trauma; moreover, I appreciate a superhero struggling in this way, because it’s a damaging lie that anxiety just happens to the weak and spineless, and because seeing someone like Iron Man work through it can be an inspirational thing. Although it’s also fair to note that all Tony’s panic attacks are fairly brief and pretty much disappear when the plot needs them to, which I do find a little less inspirational. They also never strike in the middle of a battle; compare this to Natasha Romanoff needing an admittedly legitimate sit-down on the Helicarrier in The Avengers or Scarlet Witch panicking and needing a pep talk before rejoining the fray in Avengers: Age of Ultron. Both moments are fine when taken on their own, but it bothers me that lead male heroes seem much less likely to freeze up when lives are actually on the line.

FAINTING

Used for comedy in pretty much every genre and rarely played straight with any male character, much less the hero. (Unless, of course, that hero has succumbed to illness or blood loss.) Some (but certainly not all) examples of men swooning for comic relief: Bilbo in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, Gordy in Stand by Me, multiple students in Dracula: Dead and Loving It, and both Stiles and Liam on Teen Wolf. There’s also Ichabod Crane in the 1999 film Sleepy Hollow, who must win some kind of record, as he faints, I believe, five separate times in that movie. I find Crane interesting, though: on one hand, these multiple fainting scenes (along with his fear of spiders and general prim behavior) are pretty much the epitome of playing fear for laughs; on the other hand, it’s actually the sheer number of these moments that make Crane stand out to me because, funny bits aside, Sleepy Hollow is definitely not a comedy, and there are very few dark fantasy/adventure/horror films which allow their male protagonists to be this consistently fearful and still the primary hero.

Other possible subversions: Harry Potter passes out repeatedly in his movies, particularly in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, but I’d argue that this usually seems borne out of injury, not fear. Even his encounters with the Dementors are shot to look like physical attacks: Harry isn’t fainting merely because some caped guys frightened him and drained him of all happy feeling, good Lord, no. He’s simply passing out because the wannabe Nazguls are trying to suck his face off, as one will do.

I find Neo from The Matrix interesting, though, particularly his reaction to learning the truth about the real world: he panics, vomits, and immediately passes out. It’s one of the only film examples I can think of where a man fainting from a panic attack isn’t meant to be funny. Not to mention it’s just nice to see someone have an appropriate reaction to their entire worldview being upended. Compare Neo to, say, Captain America at the end of Captain America: The First Avenger, who is told that he’s (essentially) time-traveled about 70 years into the future. Somewhat hilariously, Nick Fury then asks if Cap’s going to be okay. Cap’s response: “Yeah. Yeah, I just . . . I had a date.” And NOPE, uh-uh. Not having it. Is this a poignant and sad moment? Sure, absolutely. Realistic? No. Oh my God, no. If ever there was a reason to faint in the middle of the street, it’s waking up and discovering that almost everyone you know is probably dead.

CRYING/WHIMPERING

Also well outside the range of how male heroes are typically allowed to portray fear, as crying and whimpering (much like fainting) are behaviors many people associate with weakness and/or femininity in a negative way, as the two unfortunately often go hand-in-hand in common vernacular. (Think “throw like a girl,” etc.) Men who are so frightened they begin to cry or whimper are usually around to provide humor, and even when they’re not, it’s rare to see the hero of a story providing the tears. Once again, it’s often the cowardly or weaker side characters who tend to cry from fear: for instance, Samwell Tarly in the second season finale of Game of Thrones, or Chunk when captured by the Fratellis on The Goonies.

Genuine subversions seem rare. Obviously, Joe West is one example. Another pretty good one is Nick Stokes from CSI, who cries when he’s held at gunpoint in the first season, and completely panics when he’s buried alive in season five, crying, screaming, and at one point totally incoherent from fear. It’s pretty good stuff.

BEGGING FOR MERCY

Finally, this one is leagues outside the Standard Heroic Range, presuming the hero in question is genuinely pleading for his own life. A hero can genuinely plead for someone else’s life, or he can pretend to beg in order to stall for time and gain the upper hand: Judge Dredd does this in Dredd, as does Josh Hartnett’s character, Calden, in the long forgotten Hollywood Homicide. But heroes who genuinely beg for their own lives? That pretty much never happens. I’m really struggling to come up with any new examples to add to the ones I’ve already discussed.

And really, why is that? Is it such an unfathomable thing, that a hero might be terrified of dying? Is a man really less of a man because he does not meet death with composed dignity? The bad guys in Dredd and Hollywood Homicide are both disgusted by their respective hero’s cowardice, but the real question is would we, the audience, be disgusted if it weren’t all a ruse? Can you see Netflix’s Daredevil–the Man Without Fear–sincerely begging for his life? How about any of the male agents on a criminal procedural like NCIS? Even McGee, the least alpha male of the agents, seems pretty unlikely, right?

And what about the other atypical fear responses we’ve discussed? James Bond struggles with his aim and a vague sense of doubt in Skyfall, but would you still consider him James Bond if he suffered from crippling panic attacks that struck in the middle of missions? Everyone knows Indiana Jones doesn’t like snakes, but could one cause him to faint in a movie without it being a joke? Can you watch this scene from Jurassic World and picture our manly man hero Owen whimpering like that obvious Red Shirt who gets eaten? And can you imagine Batman–even Batman dosed on Scarecrow’s fear toxin–being so scared of anything that he actually starts to cry? (If this happens in in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, do let me know–or of any other subversions you’d like to share–because as of this writing, I haven’t made myself go see it yet.)

The truth is that I don’t see of those heroes venturing far outside the established Standard Heroic Range. But just because I have a hard time imagining Hollywood subverting these expectations doesn’t mean I think audiences would necessarily reject them if Hollywood decided to surprise me. Some people would reject them, of course: I don’t think there’s a thing on this Earth that everyone universally agrees on, even obvious fundamental truths like the fact that Peeps are a vile candy and should be incinerated and then widely scattered, so that their ashes can never coalesce and return from beyond the grave. I digress. But sometimes I wonder if this is one of those things that Hollywood has decided for us, like how executives still seem terrified of making a female-led superhero movie, despite the evidence that there are plenty of successful action movies starring women. (And obviously even more now, since that article was written in 2013.)

Because the thing is, many of those subversions I mentioned before? There was a fair amount of positive response towards them: EW and TV.com both commended Jesse L. Martin’s raw terror in “Grodd Lives.” Reviews on Tony Stark’s state of mind in Iron Man 3 were divided, with some praising the film for allowing a superhero to suffer from psychological damage and others arguing that his panic attacks weren’t depicted realistically enough, but rarely have I seen people complain that Iron Man should have somehow been above all that. And even back in 2005, Nick’s utter panic in CSI was pretty well received; a website called CSI Files compiled reviews of the two-part episode, and a fair number of them specifically note George Eads’s excellent performance.

Hollywood loves its fearless, ultra-masculine heroes, and admittedly, they can sometimes be a lot of fun. But bravery isn’t the same as being fearless, and I’d like to see more brave heroes on the big and small screen; I’d like to see them have more moments of panic, of vulnerability, moments where they work through their genuine fear to save the day. Because if there were enough of those moments, Real Men Feeling Fear wouldn’t necessarily have to be a noteworthy subversion; it could just be accepted that men aren’t somehow less manly for being afraid. (And hopefully, by extension, we could address crappy gender perceptions that link femininity with fear and weakness, too!)

It’s a tall order, I know. But the world is changing out there; a lot slower than many of us would like, yes. But it is changing, and our heroes ought to continue changing with it.

7 Comments

Gerd D.

April 14, 2016 at 10:41 amAs an aside, to add to the Iron Man 3 praise – this is also the only Superhero movie in which a male hero not just needs (and aknowledges it, a novelity in itself) help but at the end gets saved by the female lead, which after the rather typical female support role Pepper played in the first movie really positively surprised me.

Couldn’t think of an example of a male hero showing true fear, but then I grew up watching Chuck Norris movies, who as we all know is what the things under the bed fear.

Hebe

April 14, 2016 at 1:40 pmI wonder if there’s something about comfort going on here as well – I’ve always found films that are emotionally honest about fear a lot more uncomfortable to watch than those that aren’t. Usually better, yes, but also harder to watch. Hollywood blockbusters are almost always trying to play to the widest possible audience, which makes being easy to watch a primary aim. Imagine trying to watch a film like The Hobbit if its protagonists were actually as afraid as they should be – it just doesn’t work.

Alyc

April 14, 2016 at 2:38 pmReally interesting article. A data point to add to the list: Westley, in one of the few really human moments not played for laughs in The Princess Bride. We’ve seen him swagger his way through the Fire Swamp and face off against Count Rugen when the odds were truly stacked against him. He confidently tells The Albino that he can cope with torture, but The Machine breaks him into quiet, helpless sobs.

Kirsten

April 14, 2016 at 3:56 pmI love The Princess Bride for so many, many reasons and this is one of them. Also, the scene when Inigo finally gets to say his line to the Count and the Count… RUNS. It’s funny in a way, but I think people laugh mostly out of surprise because it’s just not what you’d expect to happen. The run isn’t played for laughs. The Count is scared.

It’s another thing I love about the first Die Hard movie. John spends a lot of time looking afraid, confused, and overwhelmed. Sure, he ends up in the IDGAF mode, but at first he’s talking to himself, yelling at himself, pacing, sweating, and trying to remember where he is when he’s going through the guts of the building. When Tagaki gets shot, he jumps back so fast that he bumps his head on a table. When he has to jump off the roof he’s freaked and he has a pretty good response post-jump when he has to get that hose off of him before it drags him out the window. When he’s picking glass out of his foot he’s whimpering and tearing up and is pretty sure he’s going to die. It makes him way more relateable than other action heroes.