Octavia Cade is the author of Book Smugglers Publishing’s The Mussel Eater. Food & Horror is the monthly food-and-horror series by Octavia that will be appearing on The Book Smugglers over the year ahead. Tune in next month for a stickier exploration of food-as-tool in horror…

Tools of Nurture, Tools of Torture

Food is regenerative, and transformative. It’s the energy source, the fuel for our cells. What we eat turns into flesh, replacing the matter we lose every day… skin cells sloughing off, hair falling out, mucus and bile and the soft sinking calcium of aging bones. The meats and milks and meals we eat are transformed, through our digestive systems, into flesh and blood, into muscle and bone and brain matter. This is biological transformation, biological regeneration – but there’s metaphorical regeneration as well, passed off for fantastic biology as it often is – and it’s this regeneration that turns up so often in horror.

Oftentimes the regeneration is specific. The mutant serial killer Virgil Incanto, who appears in The X-Files episode “2Shy”, is absent of body fats. Without them his skin degrades, inelastic and coming off almost in chunks. In order to remedy this deficit he targets overweight women, luring them on dates, opening them up in more ways than one, for when Incanto seduces them enough for kisses he vomits digestive fluid into their mouths. This viscous stomach acid first suffocates his victims and then breaks down their fatty tissue, allowing him to suck it into his own body, to regenerate his appearance. “2Shy” is a study in appearances, in sexuality.

This serial killer’s after the fat of breast and belly and soft, wobbling bottoms, for if his victims don’t share the confidence of Rubens’ painted women, they definitely share the stature – and it’s only after taking the external characteristics of their sexuality into his own body that Incanto is attractive enough to successfully stalk his next meal. “The dead are no longer lonely,” he says, after he’s finally been captured, and part of the reason for that is that they’re with him always, lubricating his cells, keeping his gullet moist and smooth, unshredded. No wonder he woos those soon-to-be dead women with honey-words, with flowers and ancient Italian love poetry. Dining out is, after all, a sensual experience.

The X-Files has a particularly successful history of body horror and cannibalism, the most effective example of which is probably Eugene Victor Tooms. This monster antagonist of “Squeeze” and “Tooms” needs livers rather than body fat, and in a hibernation cycle that rouses him every thirty years he eats five livers before sinking back into sleep. These livers are ripped, bare-handed, from their still-living hosts, who promptly die from shock and blood loss.

They also die because they lack the regenerative capacity; it’s been taken from them. Agent Scully states, in her report of the investigation, that “The liver possesses regenerative qualities. It cleanses the blood”. She posits that the killer takes the liver in order to cleanse himself of his own impurities – and if The X-Files dealt in anything but monsters and metaphor, she might well be correct. But metaphor is the life-blood of the show, and Tooms gobbles down his organs body-fresh because of biological necessity – or I should say apparent biological necessity, for in his case the livers cleanse not sins or mental breakdown or the demented biology of monsters, but the natural, human threats of mortality and age. They are metaphorically regenerative, and Tooms survives hibernation after hibernation, never aging, a mutant in a nest held together by bile, waiting to wake and gorge again.

But for all Tooms’ ruthless efficiency, I never got the impression that he was particularly bright. Canny, yes. Instinctual in his movements, in his ability to blend in and pass beneath. But he wasn’t feeding for eternal life – how much life is there in decades of sleep punctuated with brief moments of manual labour cut with murder? Unless there’s a particularly active dream-life we never get a hint of, his natural state is unconscious.

Contrasted with this is the very directed, intelligent community portrayed in the second season episode “Our Town”, where cannibalism is practiced primarily as a means of getting – if not eternal – then certainly a substantially elongated life. Local residents disappear to the cooking pot, a communal meal that only comes to light when one of the victims, infected with Creutzeldt-Jakob disease, manages to infect everyone who stuffed down his boiled-up carcass. In this community, cannibalism may have prolonged life and youth but it does so at the cost of insanity and dementia – not to mention the chicken factory at the centre of it all, where the remains of the founder end up being fed to a different and wider population, another rung on the food chain… The regenerative has become degenerative, the infected brains disintegrating into a spongy texture full of holes, a mimicry of the community that feeds on itself – and indeed the happy family workforce of Chaco Chickens has started eating its own members instead of the neighbouring outgroups.

Yet consumption for the purposes of regeneration need not be total. It’s almost more horrifying when it isn’t. The Countess Bathory, staple or bit-player in so many horror stories, may bathe in the blood of virgins to regenerate her own appearance, to keep her skin young and smooth and supple, but once a virgin has been emptied into her bathtub then that’s the end for the virgin. The horror’s over, there’s nothing more that can be done to her. It’s a horrid ending but at least it’s a quick one, and quite different from that other bathtub conclusion wherein a hapless victim wakes in an icy tub, stitches all up their side and with their organs gone to nourish another body.

That ending is also a beginning – the start of the rest of life, the months and years the hollow host has to suffer, full of trauma and limitation and scarring.

Those years can be short. There’s a variant on the Bathory type of regeneration where it’s not blood that’s the catalyst for eternal life but youth itself. In these stories, the consumer sucks life and strength from the victim, leaving a formally young and healthy individual a withered shell of their former self, doomed to skip from adolescence straight to old age. That’s a really horror-filled fate, if you ask me. Not the being old (a state I hope to achieve myself one day) but the knowledge of what’s been taken from you, the sense of dislocation. It’s the death of dreams, of potential, the sudden entrapment in a body that’s almost nothing like the one you had. The awful consciousness of survival.

In the film Snow White and the Huntsman, Queen Ravenna keeps her youth and beauty by sucking life from the young women of the kingdom. We see a particular example with Greta, a pretty girl who is almost instantaneously transformed into a bent, grey creature clinging onto life. Her potential future is eaten up by the Queen, and the signs of age present in the latter disappear. It’s an almost vampiric relationship, except the victim of a vampire either transforms or dies, whereas Greta and her fellow morsels transform and then die. One can hardly call it an improvement, from the point of view of the person being consumed – but the popularity of this horror trope remains. Ravenna is only one of the later examples of such.

It’s not really accurate to call this facet of horror consumption an inversion of the original act. Food is so closely linked with regeneration – with the ability to regenerate – that the darker side of this ability is less the mirror surface of a bloody bowl than an extension of such. The horror here is what the desire to regenerate can be pushed to: how food can be used as a tool for not just bodily integrity but the survival of the ego-self. Virgil Incanto isn’t an ambush predator. He prefers to form romantic relationships with the women he’ll later digest, to give them something (confidence, the potential of attraction and the illusion of a love-relationship) in return for the nourishment he’ll get from their fat-stripped corpses. Ravenna has been so exploited as a result of her own personal beauty that she sees other women as something to be consumed as well. Neither of them lives by food alone. The methodology of their kills, the personal emotional resonance of feeding maintains self-image as well as bodily integrity. Each time Ravenna strips another woman of their future in order to reinforce her own she’s reliving her identity as abuse survivor, using her body to ensure her own future. Each time Incanto shares poetry with another doomed date, he’s reinforcing his perception of himself as something other than monster; as a man involved in some kind of mutually beneficial transaction. More beneficial for him, of course, but he doesn’t like to take without some form of relationship-payment. It’s the regeneration of self-illusion as much as anything else that keeps these two monsters slavering for more: he is not just a cruel man on the hunt for fresh meat; she has not turned into the abusers that made her to begin with. In this they justify their consumption, and the regeneration goes on.

But if food in horror can bring with it regeneration, it can also mean extinction – and not just the simple piece of poison, the easy death. Let’s look back at the “Snow White” fairy tale for a moment. The apple given to the exiled princess is transformative in that it causes her death and sends her coffin-wards, but the Evil Queen is interested in more than the death of her step-daughter’s body, and the clue comes much earlier in the piece.

“Bring me her lungs and liver,” she says the Huntsman, and when he does – or appears to do so – she has them cooked up and eaten. It’s here that the principle of inversion, of inverted regeneration, is particularly well illustrated. The detail of the liver is especially interesting. Dana Scully isn’t around to lecture the Queen on the regenerative ability of the organ, apt as it may be (the Queen is looking to regenerate her own appearance after all, to reclaim the title of most beautiful in the land), but the liver here represents more than regeneration. The liver was also seen by the ancient Greeks as the seat of the soul, and if that belief waned over the millennia it survives in odd places, in stories and fairy tales and the dinner plates of jealous queens. Snow White’s stepmother isn’t just interested in devouring her daughter’s body. She wants to eat her soul as well, to truly wipe her off the map in all possible ways; to consume her spiritually as well as physically.

Let’s also remember that the princess is her father’s only child, his one true heir. In eating her, the Evil Queen destroys not only body and spirit but bloodline. There is to be nothing left of Snow White, no potential for resurrection in her daughters and grand-daughters. Everything about her is to be eaten up, to be remade in the Queen’s own image, transformed as her offal-flesh is intended to be, into the Queen’s own body. If Snow White is food, she’s also the death of potential, of the regeneration of children. Her death is the extinction of an entire line.

The Evil Queen is not the only horrifying mother of this type to chomp her way through children. One of the typical prototypes here is the mythological Procne, whose husband Tereus rapes her sister and rips out her tongue. The women kill Procne’s son Itys and serve him up to daddy for dinner. On discovering what he’s just eaten (being presented with the severed head of his young son is a dead giveaway) Tereus chases after the women but is transformed into a hoopoe bird, so there’s no more kiddies for him. Poor little Itys is of course as innocent as Snow White ever was, but it’s hard to argue that his father at least didn’t deserve it. Still, how many people have read this rather horrifying story and wondered how Procne could do this to herself, let alone her son?

Perhaps some people just aren’t cut out to be parents.

“You’re so cute, I want to eat you up!” or so many doting mothers have said to their own babies, but not nearly so literally. Horror, however, pushes past the bonds of family and infant devotion. Parental bonds are severed, and the kid’s for the cauldron.

It’s the deliberation that’s the worst part of it; the most horrifying of what is a very nasty story on a multitude of levels. How does Procne do it, if she’s even the one hacking up the child in the first place? You can just imagine her standing there, over the cooking pot, stirring away while a tiny little foot boils to the surface and then sinks again. The different cooking times of his offal, all the little bony joints. And still there she stands, stirring away – when not alternating with her sister, for one of them’s got to set the table, to chop up onion and herbs and make the gravy, something to disguise the flavour of flesh, to give it the tinge of pork or beef or veal so that no questions are asked before it’s all eaten up.

Does she sit that little severed head on the pantry shelf while she’s cooking? Does she turn the face away, or set it so it’s watching the pot?

How much, how much does that child look like his father? Quite a bit, I reckon. There’s a family tie that’s being underlined here, and it’s not that between mother and child. She’s picked her family, has Procne, and it consists of sisters instead of sons.

As far as Procne’s concerned, all sons are good for is food and vengeance. In her case, that vengeance is inspired by a deliberate act, although in the fairy tale “The Juniper Tree” the offense is far more passive in nature. There, the little victim is beheaded by his stepmother, who wishes her daughter to inherit the father’s estate. His body is turned into sausages, or sometimes stew, and he’s fed to his oblivious parent while the little girl, weeping, is left to bury her brother’s bones.

All the victim has done in this case is to exist; to be the elder and the boy and the son of a dead and early wife. The stepmother acts against not what he does but what he is, and the feeding of the child to his father is actually unnecessary in the greater scheme of things. She could have buried him in a distant field or left the body out for wolves and discovery – easy enough to blame bandits, one presumes, or a passing lunatic. Instead she turns him into food. Why? Is it a good way of getting rid of the body, or is she just very practically-minded and prefers to save the housekeeping money for other things instead of giving it over to the local butcher? Does she want to make sure that this particular bloodline is ended for good, fed back into its maker so that the supplemented father can provide more efficiently for his daughter? Does she blame her husband for having a life – and a wife – before her?

Maybe it’s a little bit of all of them, but it’s hard to think that vengeance isn’t in there. Feeding someone a stew made from their own child? That’s personal. That’s hate. That is grossly over-the-top malicious, and it doesn’t come out of indifference.

It comes from the desire to get your own back, as underhandedly and destructively as possible. That’s another of the ways that food can be made into a tool in horror: a tool for vengeance – but vengeance doesn’t have to be centred about bloodlines and extinction, the consumption of regeneration.

We’ve all heard the urban legends, the nasty little tricks that have reached mythic status. Ground glass in hamburger, razor blades in candy bars, the kicking back of a sick mind against a society that’s somehow wronged them. These are stories that run deep. They seem harmless enough in the midday sun, but come Halloween night there’s no end of parents carefully sorting through their kiddies’ stash, absolutely certain that their infant trick or treaters are at risk from doctored chocolate, from pins and needles in their marzipan. Psychopaths are everywhere and terrorists have been buying sweets in bulk, determined to promote ideology through butterfingers and liquorice, through little poisoned sugar mice.

It’s ridiculous. How often do these things actually happen? This wary vigilance, out of all proportion to realistic risk, but there are these stories… and we know that horror comes through our stomachs, through food, because we live in a world with an expectation of subversion, now, and food is something we can’t live without. It’s crucial, and it’s an avenue of access – a way for horror to slide inside us, to transform from living to dead, or living to merely-wishing-for-death, or living to fate-worse-than-death.

This is a world with Rohypnol in it, after all. We’re taught to be wary of what we ingest, right from when we’re young. “Let Mummy check your candy for you, or you might get sick. Don’t lose sight of your drink, or the bogeyman will get you.” And that’s not even counting the grim little stories of our cradle years. Even fruit isn’t safe! If it’s not taking poisoned apples from strange old ladies, it’s worrying about genetically modified horticulture and how it’ll bring on the apocalypse.

Because the thing about horror is, so often, that you do it to yourself. Sure, you could be innocently passing through some ancient Carpathian village, totally ignorant of local folklore and with your garlic left safely at home where it should be, unused and sprouting in the larder. You could be targeted by an unknown mutant (although there’s often blame to be shared in some way – he wouldn’t come after you if you weren’t fat or female or possessed of a working liver). These things are scary because we can’t predict them, but also scary is what we walk right into, eyes open, because a lot of horror comes with a cosmic, screw-eyed sense of justice that doesn’t have a lot of time for varying levels of innocence.

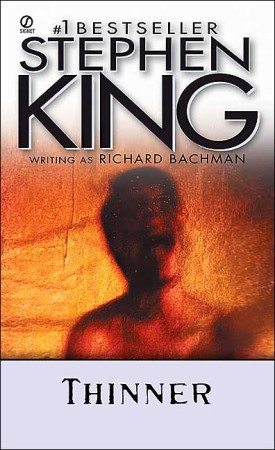

Or not-innocence, as the case may be. Consider Stephen King’s (writing as Richard Bachman) novel Thinner. The protagonist, Billy Halleck, distracted while driving (his wife’s giving him a handjob at the time, because sex and death go hand-in-hand with food and the imagery of consumption) runs over an old gypsy woman. But Billy’s well-known, well-liked, and he has connections so he gets off – or so he thinks. Leaving the courthouse a fat, free man, he’s cursed with a single word: “Thinner”. And does Billy ever get thin. The weight drops off, and off, and off, and the one thing he finally plumps on to stop his starvation only makes it all immeasurably worse, as he manages to spread the curse to his wife and innocent daughter. You want to over-indulge, the curse says, well then you just try it now, buddy.

Food is such a useful tool for vengeance, because that tool can be used in two ways: through presence and absence. Each way is transformative. Eat enough of the right thing (the wrong thing) and you can be transformed into a bleeding, pox-filled, ulcerated mimicry of man – if indeed that transformation allows you to stay human in the first place. Eat enough and you’ll be transformed into ill-health and deformation, from life to death to undeath. Don’t eat enough and you still transform, into starvation personified, into skeleton and bone, the absence of flesh.

The food-tool is very often degenerative, although in rare cases it can be regenerative as well – for instance, forcing eternal life on someone who doesn’t want it, when eternal life becomes misery and madness. Think of little Claudia from Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire. She’s not transformed out of vengeance, but she might as well be. Feeding a little girl vampire blood in order to turn her creates a monster of in-betweens, an adult mind in a child’s body, a sterile and a blunted sexuality.

The stepmother of the Juniper Tree feeds her stepson to his father to get some (unexplored) revenge on her husband. The child is unwelcome but largely irrelevant from a personal, vengeful point of view – had she wanted to use food as a tool to hurt him, rather than to hurt his progenitor, she would have used it to keep him alive as Claudia is alive. There’s no greater torture than that.

It’s a torture that has its roots in temptation. Food rates pretty high on the desire scale – think of truffles and chocolate mousse and lobster with butter; there’s a reason they call it food porn. Some cookbooks have the sensuality of an erotica manual (even the language is the same). It’s no surprise then that horror is one of the many, many genres that use food as a tool for temptation.

Sometimes it’s flatly obvious: last month I talked about the gingerbread house, purpose-built to lure children into the service and stuffing of ovens. Similarly Edmund Pevensie, bribed into betraying his family with Turkish Delight, the sweets opening the door for magic and belonging and pride; and Snow White abandoning all good sense (and the memory of previous disasters) for an apple.

It’s food as a bribe – and food is a good bribe, especially for those – like children, for instance, or non-human creatures – who can’t be bribed with sex. (“Please, dragon, take this virgin for your supper and don’t burn down our town!”) It’s a bribe that comes with the promise of transformation, but because we’re looking at horror, that food-transformation comes in a variety of nasty permutations. It can be used to transform others or to transform the self (both these come with the possibility of unexpected results, of the be-careful-what-you-wish-for type). Even the prospect of regeneration is double-edged – and so is the use of food-as-tool. It’s temptation for the poor sucker on the end of the tasty offer (“You eat the windowpane, Gretel, I want to try the roof tiles!”) but it’s also temptation for the person offering the food to begin with. If you can get your heart’s desire by dipping half an apple into poison and stuffing it down the throat of some pretty, greedy brat then why the hell not! It’s not as if you’re a nice person to begin with, that fruit’s just taking you a little bit further down the road of rotten-fucking-appledom.

That’s horror alright, turning you into something worse no matter what side of the fence you’re on.

Food is a good lure because it matters. Every community bonds over it. Food is family and friends, kinship and ritual. It binds people together. It feels good, tastes good, smells good. It often has religious connotations of transformation – bread masquerading as flesh, wine as blood and they call it communion, for bringing together. It’s nurturing. Through ritual and transformation it keeps society and biology intact.

Horror destroys; it does not nurture. It breaks down bodies and communities, transforms and builds them up (or down) into new and freakish forms.

Food is one of the fundamental shared experiences of humanity, and that’s what makes it so ripe for horror, because all these good shared things are capable of subversion. Poor monstrous little Claudia isn’t fed into vampdom as a means of punishment: her vampiric father is tempted into forming a family, to bond through blood and food and kind, and he never stops to think about how it will all turn inevitably to torment and hell. Even Edmund, dazed by Turkish Delight as much as his own (unjustified) sense of self-importance is lured, by food, into the desire to form a family with the White Witch. Virgil Incanto takes his victims on romantic dinner dates; the gingerbread witch feeds Hansel and Gretel well before tucking them into little white beds like a parent and telling them to sleep well, my dears, I’ll see you in the morning. We’re so lucky to have found a new mother, they whisper to each other, full as ticks, transformed into complacency and, frankly, ingredients.

Food, such a humanising influence in reality (the festival rituals of feasts, the family dinners, the generational teaching of traditional and beloved recipes), is a dehumanising tool in horror. Sometimes literally, sometimes just by the transformation of a human being into a prey animal – a creature undeserving of empathy or consideration. Which is, coincidentally, what this column’s going to be about next month: Jaws and Jurassic Park and giant saltwater crocodiles… creature horror and food, the dehumanisation of ourselves in horror, nature red with our too-easy blood in tooth and claw.

But until then, consider the uses of food as a tool in horror: transformative, regenerative, tempting and deathly.

8 Comments

Tools of Nurture, Tools of Torture | KiwiWalks in Speculative Fiction

December 30, 2015 at 7:32 pm[…] on Food & Horror that I’m writing for Ana and Thea over at The Book Smugglers. It first appeared on their site a month […]