The Grace of Kings is excellent in many ways and highly disappointing in one major aspect. There is a lot that that can be said about it but my review will concentrate on structure, narrative, ideas and… women.

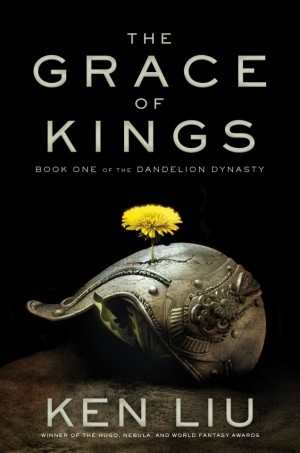

Title: The Grace of Kings

Author: Ken Liu

Genre: Epic Fantasy

Publisher: Saga Press

Publication Date: April 7 2015

Hardcover: 640 pages

Wily, charming Kuni Garu, a bandit, and stern, fearless Mata Zyndu, the son of a deposed duke, seem like polar opposites. Yet, in the uprising against the emperor, the two quickly become the best of friends after a series of adventures fighting against vast conscripted armies, silk-draped airships, soaring battle kites, conspiring goddesses, underwater boats, magical books, as a streetfighter-cum-general who takes her place as the greatest tactitian of the age. Once the emperor has been overthrown, however, they each find themselves the leader of separate factions—two sides with very different ideas about how the world should be run and the meaning of justice.

Stand alone or series: First in the Dandelion Dynasty Trilogy

Format (e- or p-): eBook

Review:

I’ve been a Ken Liu fan for a while – his short stories are great and I loved his translation of The Three Body Problem by Chinese author Cixin Liu, one of my favourite books from last year. I’ve been anxiously waiting to read The Grace of Kings, the first book in the Dandelion Dynasty trilogy.

An epic fantasy novel, The Grace of Kings is a reimagining of the rise of the Han Dynasty gracefully mixing elements of Western and Eastern storytelling traditions. It’s been labelled “silkpunk” with the silk part stemming from Chinese aesthetics and traditions and the punk bit correlating to the idea of change and revolution that runs throughout the novel.

The Grace of Kings is excellent in many ways and highly disappointing in one major aspect. There is a lot that that can be said about it but my review will concentrate on structure, narrative, ideas and… women.

The grace of kings is not the same as the morals governing individuals.

The Grace of Kings is ostensibly a story about revolution and change, centring in the uprising against Emperor Mapidéré who, only but a few decades before forcefully united several fiercely independent kingdoms under his rule. His vision for a “better future” all but falling apart in a few months. The ensuing years follow the rearranging of Kingdoms, the fights between factions, the rise and fall of Kings, Princes, Marshalls and Generals as well as the struggles of the people.

This novel contains multitudes in its scope: from minor character to major character, from the philosophy of ruling to ground-breaking questions regarding taxation, from the use of brute force to thoughtful or tricky diplomacy, from beautiful poetry to bawd songs, from love stories to grandiose friendships, from observing basic structural support for marching armies to building revolutionary technology, everything has been thought through in an awe-inspiring way (how the author kept track of all the different strands I can only but begin to imagine) and the sheer amount of names, places and people is mind-blowing.

The chosen structure and narrative mode lend themselves well to this scope. The former appears in the way that the story is divided in short sections within chapters, each following different storylines and characters. I feel this was a great choice given the author’s mastery of the short story format. Each individual thread a short narrative, a piece of a puzzle that when put together form a striking, coherent picture of a complex, diverse, divided world like nothing I have seen before.

The latter comes through the omniscient narrative, head-hopping from character to character. And there’s a lot of them. A. Lot. Of. Them. Some breeze through and disappear like lightning bolts. Others linger and stay. This is not strictly-speaking a character-driven novel but this is not to say that some characters aren’t well developed.

Two fleshed-out main characters emerge from this vastness: Mata and Kuni who begin as friends and end up on different sides. The story builds itself around these central figures – spiralling away and back again to them. Kuni and Mata in fact, embody the main thrust of the novel, the one where the question of “better future” is up for discussion. For larger-than-life aristocratic Mata the “better future” is to go back to the traditional ways of the past where honour is more important than anything else. For small-town bandit-commoner Kuni, it means embracing change and difference. Who is right, who is wrong, doesn’t really matter. It is very clear here that this is not the point: momentum, alteration, ever-changing landscapes are. Tradition versus modernity, unification versus divide, what is better for the whole? No easy answers are given and it’s foreshadowed that things will only get worse before they get better.

In the midst of it all, clever deconstructions of traditional epic fantasy take place. Violence is there but not in gory detail. There is no lingering gaze when lives are lost and perhaps that makes it all the more arresting. The Gods are actual existing characters that often come to the foreground as though they are a Greek Chorus and come across as meddling children who have little actual power. Oh, they try. But mostly their meddling fails when faced against clever, free-willed humans. This is actually funny.

Also on the “fun” side? A whole epistolary chapter with delightful letters between Kuni and his wife Jia.

Jia. Who is one of the few female characters in the novel with any substantive role to play. Who, for the first 77% – SEVENTY. SEVEN. PERCENT – of the novel was its main female character out of countless, countless other characters.

What about the amazing Princess Kikomi, Ana? She appears before the 77% mark, you might say. Oh yes, she does: and she gets killed and fridged in the blink of an eye.

But allow me to backtrack a bit because there is a whole conversation to be had about the women in the novel, the way they are presented (or not), the motives behind this authorial choice and my feelings about it all.

A lot has been said about the lack of women in The Grace of Kings. A quick glance at Goodreads, shows me that most reviewers share my frustration when mentioning how for the first two thirds, apart from Jia, the governess Soto and the brief appearance of Kikomi, there are very few female characters appearing at all. When they are briefly mentioned, they are prostitutes, dancers, mothers, wives, who all play those very specific roles when they appear (Kate Elliott wrote an interesting take on this and the comments on that thread are well worth a read).

At the 77% mark Gin – a warrior, the only female character to participate in the plot in that manner – is introduced and The Grace of Kings changes gears and all of a sudden women are everywhere. It is as though a fuse has been lit and the light shines in all corners of this world. Kuni as one of the main viewpoint characters and as a leader, becomes increasingly interested in the lives of women. From that point forward, women now participate in the narrative in a big way: several more characters are introduced and allowed to enter the head-hopping dance. And it is freaking amazing.

It is very, very clear the long game being played here. This is a traditionally misogynistic world. Women are relegated to the background. And the author not only does question this in a myriad of ways from the start but provides different voices within the narrative. When a character feels uncomfortable about being compared to women, we are supposed to disagree with him. When Princess Kikomi questions her existence, we are supposed to sympathise with her. The narrative does NOT support misogyny. The challenge, the questioning are undoubtedly there.

However.

I question the way this challenge has been done and I’d like to argue that this is not completely successful.

Because there are mostly male voices. Because Kuni – a guy – is the one to appear the really smart one when talking about women. Because when Gin appears, she appears out of nowhere (tell me one reason why she couldn’t have been there from the start, even if in a male disguise?). Not only that but she is also excepto-girl, “the only one” to fight, to want to fight. She can’t even imagine OTHER women fighting until she is told to bring more women into the army. And hey, they are brought in as kite fliers because they are “lighter” than men in a really simplistic and dismissive way.

But more than that, here is where I feel this long game fails. Allow me to briefly remind you that the narrative mode here is omniscient. The novel contains a multitude of characters, the narrative head-hops around countless – so countless, it is easy to get lost – people. And yet, for the most part, this is a novel of dudes, a world of dudes and we spend most of the time reading from the inside of dudes’ heads.

But here is the thing, because of the narrative mode, it makes no sense to leave women out to the extent that it has been done here. The world might be misogynistic, the women might have had fewer opportunities but they should still be there. It is not that the women are powerless, or have little opportunity, it’s that the narrative itself renders them invisible, regardless of what they are or not doing. They are simply not there. And this is a huge, unforgivable problem in an otherwise awesome novel.

The fact that the novel becomes increasingly better and better once the number of female characters increase only – paradoxically – made it worse for me. Why couldn’t I have had had this experience from the start? Why once again, are we allowing men to have the better experience when reading a novel because they are better represented?

When reading The Grace of Kings, I kept hearing from folks telling me and other readers: “just wait until the ending”, “it gets better after 450 pages”, this is all part of “a long game”, there is a “gamble” at play here, “you will see”.

I cannot begin to tell you how much I resent – and a lot, it appears – this. The lives of women are not a “long game”, sorry. I don’t want to be “incremental woman”, you know, one who appears only when it’s convenient after a point has been made, regardless of the obviously good intentions behind this choice.

Reaching the end of this review, I find myself in a conundrum I have no answer for at the moment.

Like I said in the beginning, there are such excellent things about The Grace of Kings and the book gets better and better toward the ending. The female characters, when they appear, are wonderful.

Are those enough to counterbalance the invisibility of women in the first part of the novel?

Rating: I don’t know! 10! 0! 5? What is good, is so good, it pains me to even say how frustrated it made me.

Buy the Book:

(click on the links to purchase)

13 Comments

Paul Weimer

April 21, 2015 at 8:20 amWhy couldn’t I have had had this experience from the start? Why once again, are we allowing men to have the better experience when reading a novel because they are better represented?

I suspect that, for better or worse, that Liu wanted to show an evolution, change and development of his culture, society and world. This is an epic fantasy that embraces and uses change, rather than looking back to a fallen past. Innovations occur throughout the book, in food, in technology, and yes, the role of women. That evolution would be harder to show if women were already in that role.

That said, I can totally see how female readers could feel cheated by this. It kind of reminds me of another epic fantasy which felt very conventional to me, even as the author mentioned that in future novels, those conventions get challenged and subverted.

Sometimes, you DO want the “Fun now” rather than the “fun later”.

Betsy Dornbusch

April 21, 2015 at 9:25 amHmm. I haven’t read the book but have been looking forward to it. I don’t see how change around female roles can happen without females playing an active part in the narrative. Otherwise it makes me suspect patriarchal-driven change. I’m also not a patient reader… so “it gets awesome later” isn’t enough for me. That said, I’ll still give it a try.

Jonah Sutton-Morse

April 21, 2015 at 11:30 amI’ll say briefly that as a male reader I also felt disappointed by the treatment of women in this story, so that reaction isn’t entirely gendered.

@Paul – Clearly you’re correct that the book is telling a story about development and the possibility of change rather than a return to existing levels, and equally clear (maybe even overly clear) that The Point (in a book that has many capitalized Points) is to use the first part of the book to critique a genre that has historically ignored women by pointedly ignoring them, including one episode with a woman who is immediately killed, and then flooding the last third of the book with women to show another way to tell heroic stories and include women. But I take issue with your comment that

“That evolution would be harder to show if women were already in that role.”

What Liu, Leckie and a host of other authors have shown me recently is that it is very possible to take on the trappings of a genre while critiquing and improving it in ways that I (the reader) couldn’t have imagined. I can’t tell you exactly how Grace of Kings would be written with more women featured prominently earlier, but I believe it could be done, and done in a way that still preserves the marvelous structure, the bromance of Kuni & Mata that comes to such a satisfying conclusion around the 2/3 mark, and all of the other elements that I loved about the book.

It seems that over & over again when the role of women is brought up in this book, there are two answers offered (and yes, I’ve offered both, and am reconsidering that):

1 – It’s a conscious choice; or

2 – The first part is a critique of the genre, and the second bit is where you get all the wonderful women, it’s a long game.

That it’s a choice doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be discussed, critiqued, and disagreed with. That the way the book (by a male author) chooses to critique the genre is playing up the tendency to ignore women doesn’t mean it’s the only way to offer such a critique, or that putting lots of women into the story in wonderful ways later somehow makes up for it. I think Ana very effectively pointed out the problems with the second answer.

I loved Grace of Kings. It’s easily my favorite book this year, and I think if some of the innovations in form don’t make their way back into other books in the genre, we’ll have missed a huge opportunity. I’m sad that right now there are a bunch of reviewers (mostly women) reacting to the way that women are portrayed in the book who are greeted by a chorus reminding them that this was deliberate and is part of a long game, with I think an implied message that either this was the only way for the book to offer this critique (nonsense and an insult to the author) or that they should ignore this huge glaring element that the book makes a huge glaring element. I’m sad because it seems like a knee-jerk defensive response (I’ve offered it as a knee-jerk defensive response) that tries to shut down criticism, and I’m sad because it means that the discussion of this book continues to revolve around the role of women & choices involved when there are a lot of other things I’d like to talk about.

@Ana – thank you for this review, and in particular for getting straight to the heart of why this choice to defer so many of the women to the end of the book is a problem. This line in particular brought home to me the impact of this choice:

“The lives of women are not a “long game”, sorry. I don’t want to be “incremental woman”, you know, one who appears only when it’s convenient after a point has been made, regardless of the obviously good intentions behind this choice.”

Also, thank you for offering a review that can forcefully make this point about the role of women, while also speaking to the short narratives (which absolutely play to Liu’s strengths) and how they come together to create a greater whole.

Kurt

April 21, 2015 at 4:38 pmThis specific point doesn’t seem especially fair. It’s Jia, Kuni’s wife, who first draws attention to how the talents and potential contributions of women are being squandered. Kuni then feels silly for not thinking about it before, acknowledging his own gender-based blind-spot, and he specifically gives Jia credit in his letter (“And how prescient of you, my Jia!”).

Jordan White

April 22, 2015 at 12:27 amThis review was very well done. As someone else mentioned, I really found the remark you made about how Liu weaves many different short stories into a great jigsaw puzzle of a narrative was a great point. I especially liked that you challenged and criticized how women were portrayed in the book. You make a lot of good points about how in the first 2/3 of the book the only female characters were Kicomi, Soto, and Gia. It is obvious that you have done a lot of research since you have read his other works. Something that I plan to do as soon as I get my audible credits.

The only flaw I can think of in this review can be summarized in this one sentence. “Rating: I don’t know! 10! 0! 5? What is good, is so good, it pains me to even say how frustrated it made me.” This to me can be compared to a runner who was doing well in a 10k tripping and getting knocked unconscious at the 100 meter line. It just makes the review seem indecisive and not well thought out. This is especially sad because I pretty much agreed with you on everything and the rest of the review was the exact opposite of the ending. It just seemed that this problem could have been easily solved by getting up from the computer to take a break, weighing the pros and cons of the book, rating every point you made, and by doing this you could give the book a rating that takes all of the excellent factors you mentioned into account.

Personally your review changed how I would have rated this book. I now would give it an 8 out of 10 instead of my orgasmic 10 I would have given it after finishing listening to it. From how upset you seemed at the portrayal of women in the book I assume you would maybe rate it a bit lower though.

Overall I really did enjoy your review and feel that it really changed my perspective on how I feel about the book a little. I hope that Ken Liu adds more interesting female characters in the second book. You are right, when Gin Masoti was added, things really did get better not just because she was a female character, but also because she was an awesome character who should have been with Kuni Sooner. We could have avoided the boring doldrums of being trapped on Dasu. The only reason I am critical about the ending of this review is because it doesn’t seem to fit with the quality of the rest of the review. I am sorry if it seems nitpicky and mean spirited but I felt that the ending should match the rest of the review in quality and forethought.

Mieneke van der Salm

April 22, 2015 at 1:35 amWhile I was one of those voices telling you to hang in there and to trust Liu’s story-telling skills, this did resonate strongly for me. Because as much as I adored this novel for all that it did and however much I loved Jia, Gin, Mira, Soto, Risani, and Kikomo, gods love her, I do agree that I would have loved to have had them and their voices and influences there from the start.

I guess it says much at how ingrained the experience of not having women in the narrative or only rarely or passingly present in a narrative is for me, that I’m just so pleased at the wonderful portrayals of especially Jia and Gin. It didn’t occur to me to be sad or angry at having to wait until the last third of the book for them to really shine and women to become a true part of the narrative.

Ana

April 22, 2015 at 4:42 amThanks for all the comments, folks!

@Paul – “That evolution would be harder to show if women were already in that role”.

I am not sure I agree with this. Actually scrap that, I don’t agree with this at all. There could have been a lot more women interspersed in the narrative in a myriad different ways that could have at the same time shown the prescriptive way of this society without erasing their experiences.

@Betsy – good luck! I hope you find things to love about it, like I did, despite my criticisms.

@Jonah – Thank you and I completely agree. I also wanted to thank you for your comments over at A Dribble of Ink, they helped me cement my own thoughts.

Ana

April 22, 2015 at 4:45 am@ Kurt – well, actually I was talking about that point in the novel where Kuni makes that “I’ve seen the bravery of Xana’s women first hand” speech over the wall. That came before, right? In any case, HE might give Jia credit in private but he is the one to reap the results in public as he is the one who is hailed as a good leader of men and women.

Ana

April 22, 2015 at 5:09 am@ Jordan White.

First of all, I am pleased to hear that my review helped you in a way.

If I am not mistaken though this is the first time you comment here and as such you might not be familiar with my reviews and the way we do things around here? I will assume so because otherwise you would have refrained from berating me in my own space for how I do things. I often write no-rating reviews when I am conflicted, the rate often reflects my review process and my feelings. Yes, feelings. I have them and I DO hope both the review and the rate have provided you with an idea about the depth of my frustration. I was incredibly upset but that does not – in the way that you infer – prevented me from thinking thinks through.

The fact that I did not rate the book and said what I said was a very specific choice. A choice that goes back to the last lines of my review and one that underlines the conundrum I stated. Because at the end of the day, I can not quantify the invisibility of women in the book. I am glad you can do that though and that you think this question merits a whole two – TWO! – points out of ten.

Ana

April 22, 2015 at 5:13 am@ Mieneke – this realization happens to me all the time.

Isn’t it sad? 🙁

Kurt

April 22, 2015 at 11:39 am@Ana

Fair point — that speech came before Gin, but I don’t remember if it came before the singing scene. At any rate, my main point was that the developing role of women was not something gifted upon them by Kuni, but rather the direct result of actions by women. I think that’s an important distinction, although I recognize it may not be sufficient for some readers.

No disagreement here. I liked Jia’s character because I often like the brain-behind-the-throne role, which she fits into several times throughout the story, but I can see how some people would be uncomfortable with how gender factors in here.

Jenn

April 22, 2015 at 1:24 pmI’m so glad I read this. I’ve been focusing on reading books by women this year, but had been thinking of making an exception for The Grace of Kings since it’s been getting such rave reviews. But in this year I’ve become accustomed to books filled with interesting and relevant and well-written women characters, and that the contrast might be setting myself up for a frustrating reading experience.

Thanks for your honest, intelligent, and thoughtful words on the matter.

nerdycellist

April 22, 2015 at 10:25 pmThank you so much for this review! I picked this up on the strength of the reviews, despite my misgivings. I adored the world-building and Liu’s writing style, but I found myself irritated about 58 pages in, where Kuni declares he is going to marry Jia and that’s that. I realized I knew more about Mata’s long dead father and the uncle who raised him than I did about Jia. Despite the narrative hopping into her head, the only things we really learn is that she’s beautiful and picky about her future husband. That’s it. I didn’t know anything about her family, or how she felt about the changes the Imperial conquest had made to her life, her schooling – anything that wasn’t to do with her becoming a wife. I asked around and someone sent me here to read this review.

I don’t require every woman to be some sort of magical butt-kicking swordswoman. There’s nothing wrong with being a Princess or a Wife, unless the author doesn’t bother to locate the humanity of these people. Jane Austen has written some delightful and complex stories people with women whose prime goal is to go to a ball and catch a husband! But I couldn’t go on with the book, even though it’s otherwise so beautiful. I feel like he’s built a numinous world only to let me know it’s not for me.

I will probably set this aside for now and pick it up when book 2 is out, assuming women continue to play a part in the next book, but for now I have a stack of fiction where women are portrayed with agency and complexity just like the men.